On 5 October 1813 Tecumseh, the leader of the Shawnee people and head of the tribal confederacy known as Tecumseh’s Confederacy, was killed at the Battle of the Thames. With his death any serious Native American resistance against the Americans in the Northwest ended, and the once formidable tribal confederacy crumbled without his leadership.

Just under two years earlier Tecumseh’s brother, known as the Prophet Tenskwatawa had launched an attack on the Americans at the Battle of Tippecanoe. The extract below is taken from John F Winkler’s Campaign 287: Tippecanoe 1811, and details the eve of the assault.

At 11.00pm, when a relieved Brigham ended his shift, the Indians at Prophetstown had been waiting for hours for Tenskwatawa to announce that a vision had revealed victory in an attack. Finally word came. Harrison must die, Tenskatawa said. In the morning, he proposed, he would meet with the American commander, agree to abandon Prophetstown, and leave. Two warriors would linger after his departure and kill Harrison. The American commander’s death, he had seen, would leave the Americans unable to fight. A massacre would follow, and then a bounty of captives and horses.

The announcement failed to satisfy the warriors. The Winnebagos, Tenskwatawa later would complain, had been the worst. Eager for battle, they could not be persuaded to wait until the following morning. When they demanded another vision, the shaman retired to seek further guidance.

Portrait of Tenskwatawa, painted by Charles Bird King

Image from Wikipedia

When Tenskwatawa returned, he announced that the American commander could be killed that night. As other Indians surrounded the camp, warriors could infiltrate it and kill him. After Harrison’s death, the shaman had seen, the Indians would fight in darkness against Americans revealed to them by light. And the Americans’ weapons, he added, would be powerless to harm them.

Tenskwatawa left the task of planning and leading the operation to chiefs with reputations as military leaders. The Indians, they agreed, would attack the American camp in the usual way. The horns of an advancing Indian crescent would meet behind the camp to complete its encirclement. Mengoatowa’s Kickapoos would form the right horn and Waweapakoosa’s Winnebagos the left. Wabaunsee’s Potawatomis, and the other Indians, led by Roundhead, would form the base. When the Kickapoos reached the most vulnerable area of the camp’s perimeter, at its northeastern corner, a party of warriors would infiltrate the camp. When they signaled that Harrison was dead, the surrounding Indians would attack.

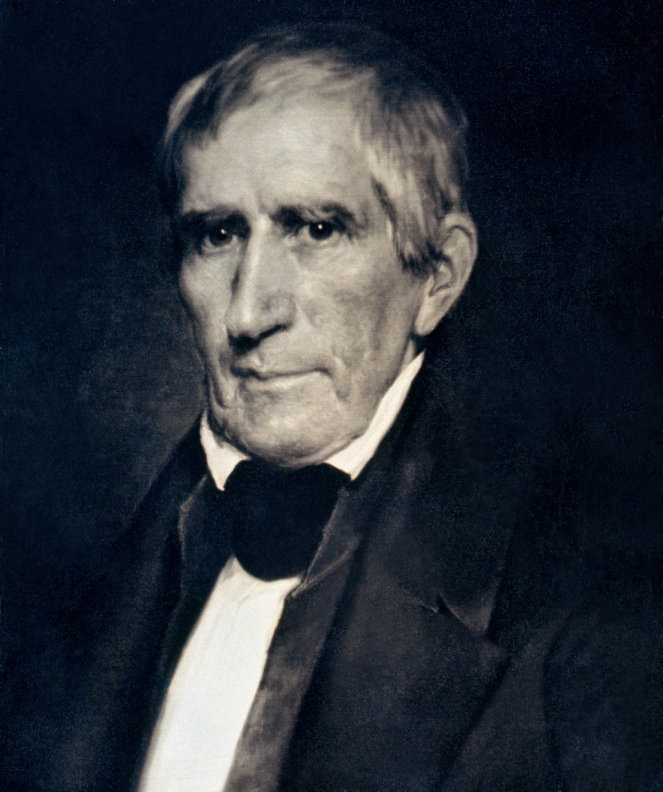

A daguerrotype of William Henry Harrison

Image from Wikipedia

It would be a massacre like Wabash, the confident Indians thought. The anniversary of the greatest of Indian victories over the Americans had been three days before. The date, Harrison had written to Eustis after crossing the Wabash River, “has been marked in our calendar for the last 20 years.” And like St Clair on November 4, 1791, the American commander now had compressed his encamped army onto a small area of high ground.

But if Harrison’s assassination did not leave the Americans helpless, there were differences between this field and Wabash that might prove important. Except along the American right and left flanks, there were no woods like those that had protected the Indians at Wabash. There they had had 1,400 warriors to surround 1,700 Americans; here they had only about 500 to encircle 1,000. And there, they had not fought at night. Here, the Indian commanders would have to use whistles and rattles made from dried deer hooves to communicate their orders.

To read more be sure to pick up Campaign 287: Tippecanoe 1811, available from 20 October. Also keep an eye out next year for our upcoming Campaign title on the battle of the Thames.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment