In the lead up to his newest book, With Their Bare Hands, Gene Fax examines the strange paradox of US-invented machine guns.

One of the paradoxes of World War I is that almost all of the machine guns used were invented by Americans, beginning as early as 30 years before the war; yet the US Army largely ignored the weapon until the early 1910s and did not purchase meaningful numbers of them until after it entered the war. This three-part article describes the development of most of the important models, why they were ignored or rejected by the Army, and how the American Expeditionary Forces eventually acquired this most important infantry weapon.

Early machine guns – multi-barrel types like the Gatling and Gardner guns and the French mitrailleuse – were too unwieldy and temperamental to serve as general-purpose weapons. They were heavy and traveled on wheels or mules, which compromised the flexibility and mobility of infantry and cavalry. They had to be hand-cranked and could not be traversed, and were usually assigned to artillery batteries, which were unfamiliar with their use. In the Franco-Prussian War they were largely ineffective, which led to a bias against rapid-firing weapons in general.

The economic, social, and technological circumstances of the United States in the 19th century led its inventors to be the first to seek a fully automated, rapid-firing gun. A century-long labor shortage impelled capitalists to substitute machinery for human effort in almost every industry. This led to continuous improvements in materials, standards, and production processes, which usually showed up first in the manufacture of firearms. The dependence on machinery created a culture of investment, risk-taking, and a readiness to automate any process. In this case, it was the process of killing.

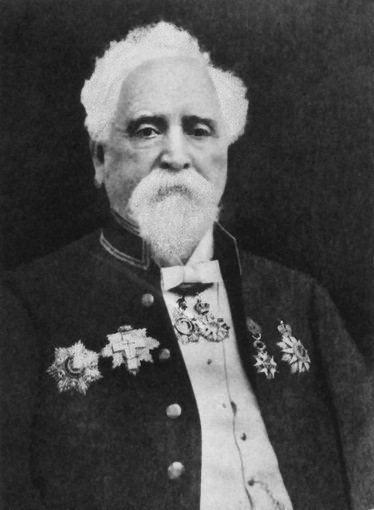

Hiram Maxim began his career as a mechanic and machinist in Maine, where he developed his inventing skills. Working as an engineer for a number of companies, he became an expert in gas lighting and quickly graduated to electrical systems. Sent by his US employer in 1881 to demonstrate its wares at a Paris exhibition, he found such a ready market that he relocated to Europe, opening a London subsidiary and eventually becoming a British subject.

Maxim got the idea for a machine gun while taking target practice with a high-powered Springfield rifle. He realized that the recoil force that bruised his shoulder could be used to operate a mechanism that would reload and fire the weapon repeatedly. Setting up a small workshop, he was able by the spring of 1884 to demonstrate a prototype that fired 600 rounds per minute. This led to inspections by prominent figures in the British military, including Lord Garnet Wolseley, then Adjutant-General of the British Army. Impressed, members of Wolseley’s staff urged Maxim to simplify the mechanism so that it could be taken apart, cleaned, and reassembled with the hands only. This he did, so that a broken component could be replaced in six seconds. In addition to its full rate of fire, Maxim’s design could be set to fire single shots or continuously at 10, 20, or 100 rounds per minute. The gun, fired daily, became a popular attraction at an 1885 exhibit of inventions in South Kensington. The celebrity of Maxim’s invention, both popularly and among the military, led to invitations to many social events at which he was introduced to the upper reaches of British aristocracy, some of whom were in positions to influence arms purchases. The British Government placed a trial order for three weapons, which passed rigorous fire and reliability tests. They bought small numbers of the guns, which by then were manufactured by Vickers in partnership with Maxim. These they used in colonial wars: against the Matabeles and the Zulus and in Afghanistan and the Sudan, among other places. In all cases two to four Vickers-Maxims sufficed to slaughter vast numbers of spear- or rifle-armed attackers. Still, larger orders were not forthcoming.

In 1887 Maxim took his gun to the Continent, demonstrating it against competing makes in Switzerland, Italy, Austria, Germany, and Russia. In all cases it fired faster, proved more reliable, and needed fewer men to operate than its multi-barreled competitors such as the Gatling and the Nordenfelt. Furthermore, it could be chambered to use almost any ammunition then in service. If the British were unimpressed by Maxim’s gun, the future Kaiser wasn’t. In 1887 he visited the factory and was so taken by the weapon that he ordered one with a British gunner to be sent to Potsdam to instruct his troops.

The first use of the Maxim in warfare between Western-style forces was in the Second Boer War, in which both sides used the gun. But the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5 saw the first large-scale use of machine guns by regular armies. Russian Maxims repeatedly massacred charging Japanese infantry, catching the attention of foreign observers. The British introduced the Vickers-Maxim into regular formations in 1904, assigning a section of two guns to each infantry battalion. The Germans were particularly impressed: by 1908 each infantry regiment had its own machine guns, and 14 million marks had been allocated for experimentation. Field Regulations stressed proficiency in use of machine guns.

The Vickers Machine Gun in action

The Vickers Machine Gun in action

Although the United States first tested the Maxim gun in 1888 with good results, no action was taken at the time. A relatively heavy, rapid-fire weapon was unsuited to constabulary actions against Indians and the US saw no prospect of a European-style war. The Army again picked up the Vickers-Maxim gun in 1906, experimenting with it to establish how the different combat arms could best use the weapon. The infantry liked it, but the cavalry thought it too heavy and unwieldy. That led General William Crozier, the Army’s Chief of Ordnance, to seek a weapon that would be lighter as well as simpler to make and operate.

Crozier was soon in contact with Laurence Benét, the US representative of the Hotchkiss Company, which was based in France and named for its American founder, B. B. Hotchkiss. Benét himself was American-born – in fact, the son of a former Chief of Ordnance – and a few years earlier had developed a light machine rifle with the help of his assistant André Mercié. In 1909 Crozier adopted the Benét–Mercié as the Army’s first standard automatic weapon. At 30 pounds it was lighter than a heavy machine gun but hardly dainty. It was air- cooled, cheap to make, and easy to maintain, containing only 25 parts; a folding stock made it highly portable. The Benét–Mercié continued in service until 1917, serving the Army in Mexico in 1913 and 1916. But in the field its defects soon became apparent. The infantry disliked it as too light and unable to sustain fire, and hence unsuitable for defense. The cavalry found it unreliable due to its close machining tolerances, which led to frequent jams. In trying to satisfy everyone, it had satisfied none: no one understood that both a light assault rifle and a heavy machine gun were needed.

Despite Crozier’s efforts, the Army did not incorporate automatic weapons into its combat doctrine. As late as 1917 its Field Service Regulations stipulated, “Machine guns are emergency weapons. They are used when their fire is in the nature of a surprise to the enemy at the crises of combat. Their effective use will be for short periods of time – at most but a few minutes – until silenced by the enemy.” By then there was no excuse for such a lack of vision, certainly not since March of 1915, when at Neuve Chapelle one German officer and 64 men with two machine guns wiped out two battalions of British soldiers totaling 1,500 men, 1,000 of whom were killed.

The repute of the Benét–Mercié took a fatal blow on the night of March 9, 1916, when Pancho Villa’s guerrillas attacked Columbus, New Mexico. American soldiers failed to get their Benét–Merciés into action, later asserting that the complicated loading mechanism could not be worked in the dark. The press dubbed the weapon the “daylight gun” and a congressional committee accused General Crozier of incompetence, an undeserved charge.The gun itself was consigned to the training camps. As a result, the Army entered World War I without a standard automatic weapon.

Part II of this article will deal with the Lewis and Chauchat guns, Part III with the Hotchkiss and the two Brownings.

With Their Bare Hands - General Pershing, the 79th Division, and the Battle for Montfaucon by Gene Fax will be published on the 23 February and is now available for pre-order. Click on the link on the book title to see more and place your order.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment