In today's author blog post we are joined by Mark Stille, who discusses his new Campaign book, The Solomons 1943–44.

When the topic of the Solomons comes up, people most often think of Guadalcanal in the southern Solomons which was the focus of a grinding battle of attrition from August 1942–February 1943. The importance of the battle for Guadalcanal often overshadows the rest of the Solomons campaign which lasted until March 1944 for the American military and up through the end of the war for the Australian military. In many ways, the Solomons campaign of 1943–44 was a template for the remainder of the war in the Pacific.

The object of the entire campaign was the capture, later changed to the isolation, of the Japanese bastion of Rabaul. It had been captured by the Japanese in January 1942 and was the source of the Japanese threat against the SLOCs (Sea Lines of Communication) between the United States and Australia. When this threat diminished and then evaporated in the aftermath of the Japanese defeat at Guadalcanal, Rabaul became the guardian of the Japanese positions in the Dutch East Indies and the Philippines. For the Americans to advance in the South Pacific, Rabaul had to be neutralized. The best way of neutralizing Rabaul was through air power, and this is where the Solomons came into play. If the northern Solomons, principally theislandofBougainville, could be captured, it would place Allied airpower on the doorstep of Rabaul, making it untenable for the Japanese. However, in order to seize Bougainville, the Allies had to crawl up the Solomons, beginning with the island of New Georgiain the central Solomons. New Georgia, with its key airfield became a mini version of Guadalcanal and was the scene of intense ground, naval, and air combat for several months.

Troops unloading ammunition from LCI-330, 335, and 328 during landing operations at Rendova Island, 30 June 1943.

Troops unloading ammunition from LCI-330, 335, and 328 during landing operations at Rendova Island, 30 June 1943.

Source: Naval History and Heritage Command

What makes the Solomons campaign so interesting, and so important for the outcome of the war, was the composition of the Allied force which successfully mastered combined arms warfare against fierce Japanese opposition. The bulk of the force in the Solomons was American, butNew Zealand and Australia also contributed forces. The American forces were truly combined and fought effectively as such for the first time in the war. Present in the Solomons were large naval forces and naval air forces flying from land bases, Marine ground and air forces, and a large contingent of Army ground and air forces. Leading this combined and multi-national force was Vice Admiral William Halsey. His force of personality, combined with the sheer necessity of fighting together, welded this collection into an effective fighting force.

Despite an enormous advantage in naval, air, and ground forces, the Americans had severe difficulties in sustaining their advance up the Solomons. The location of the airfield on New Georgia made it the only real choice for the first phase of the operation, but after that the Americans successfully, and for the first time, executed a strategy of island-hopping. The landing on undefendedVellaLavellaIslandafter the capture of New Georgia was brilliant, and completely unhinged Japanese defenses in the Central Solomons. Likewise, the selection of Empress Augusta Bayon Bougainville was inspired and again avoided the brunt of the Japanese defenses. The Japanese could never hope to defend every island in the Pacific which almost always gave the Americans ample opportunity for seizing an undefended or lightly defended island, and then quickly building an airfield on it to isolate a nearby Japanese garrison. This technique, first implemented in the Solomons, was a staple for the remainder of the war.

The story of the Japanese efforts to defend the Solomons was also noteworthy. For the relatively small investment of a few destroyer divisions, several divisions of troops, and several hundred aircraft, the Japanese delayed the American advance up the Solomons for the better part of 1943. The Imperial Navy fought several major battles with the USN, all at night. Its prowess in night engagements was demonstrated in the early battles, but even when the results were favorable to the Japanese, they were suffering attrition which was still unaffordable in the long run. By the end of the year, the Japanese Navy had lost its advantage in night fighting which resulted in the disaster at Cape Georgein November. The USN had established its superiority in night fighting which it would retain for the remainder of the war.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the Japanese defense was their defense of New Georgia. Though the Americans held air superiority, the Japanese were still able to move large numbers of troops to New Georgia at night using destroyers and barges. These troops possessed a high level of fighting spirit, but little firepower compared to the US Army. Nevertheless, in the face of constant attacks supported by large amounts of artillery and airpower, the Japanese stood fast for some five weeks before the Americans took the airfield in early August. After the fall of New Georgia, the Japanese prepared to defend neighboring Kolombangara Island, but the American move to seize undefended Vella Lavella upset this plan. Even so, in the face of an American naval blockade, the Japanese successfully evacuated the bulk of their troops in the Central Solomons. Another interesting aspect of Japanese operations was the close and effective cooperation between the Imperial Army and Navy. Without this, their defense of the Central Solomons would have been a disaster instead of the minor success it was. This cooperation begs the question what could have been accomplished in other areas with effective inter-service cooperation.

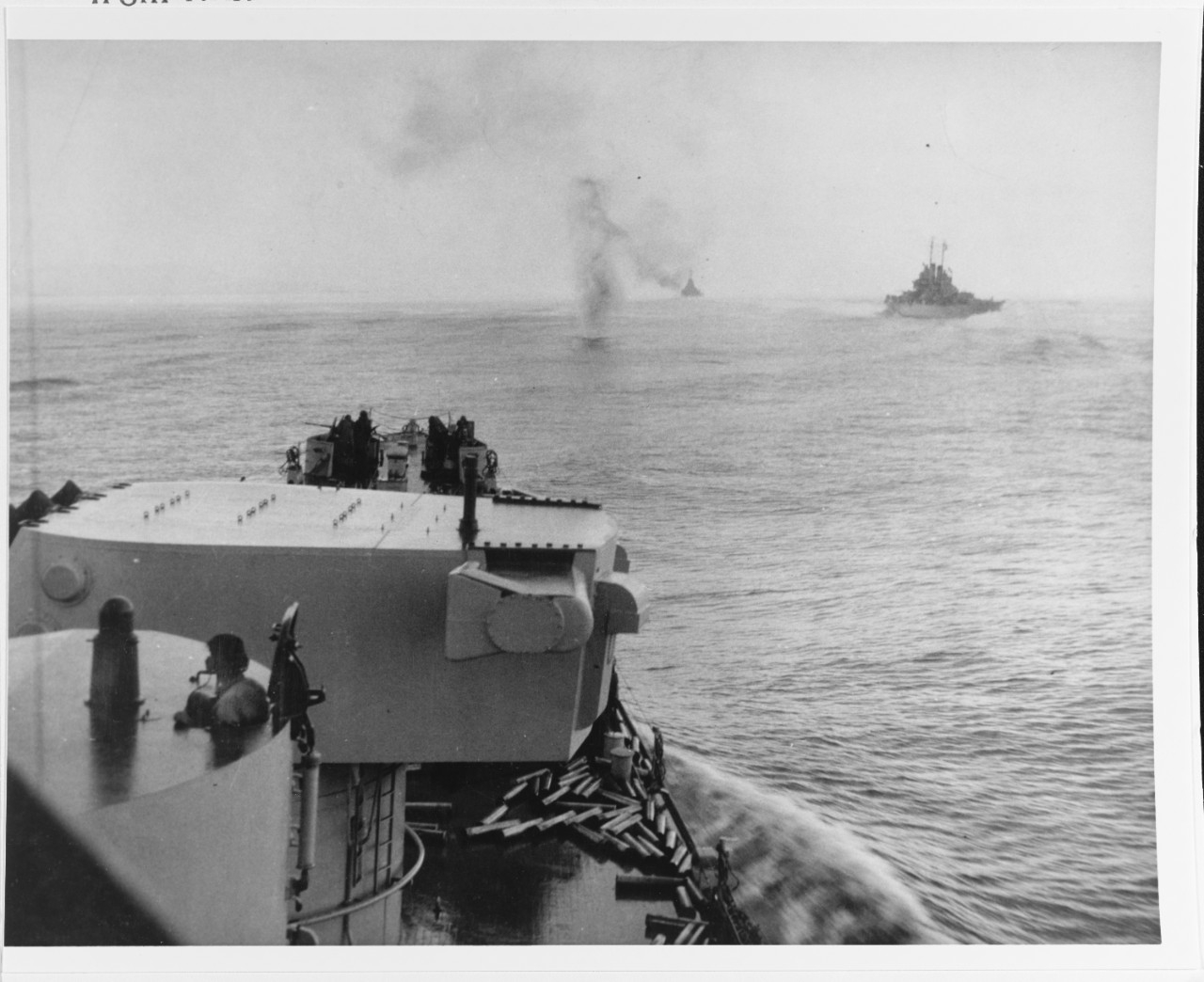

A Japanese plane plunges into the sea ahead of USS Columbia (CL-56), as she steams in

column with other cruisers during the attack on Bougainville, 1-2 November 1943.

Source: Naval History and Heritage Command

The final phase of the Solomons campaign was the battle on Bougainville. Here again, the future nature of the Pacific War was on display. The Americans sidestepped the teeth of Japanese defenses by landing on the central part of the island. The Japanese attempted to thwart the landings with both naval and air attacks, but these were defeated with relative ease. As Halsey’s staff predicted, it took the Japanese months to move a large ground force to attack the beachhead. When the attack finally came in March 1944, it featured Japanese fighting spirit against American firepower. Prepared American defenses with an unlimited amount of artillery ammunition, rendered a drubbing to the Japanese. With this, the main campaign for the Solomons was over. The only drama left was the Australian decision to take the fight to the starving Japanese garrison on the island. These senseless attacks began in late December 1944 and went on until the monsoon season in 1945 when the bloodletting finally came to a close.

The Solomons 1943–44 tells the tale of this pivotal campaign. For the better part of a year, the Allies and the Japanese were locked in almost constant combat at sea, in the air, and on islands under extreme climactic conditions. While the final result was inescapable, the Japanese fought well and exacted a heavy toll and bought time to prepare defenses in the Central Pacific. Unfortunately for them, the pattern established in the Solomons held firm for the next 18 months and resulted in an unstoppable American advance to the doorstep of Japan itself.

To pre-order your copy of this essential addition to the Campaign series, click here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment