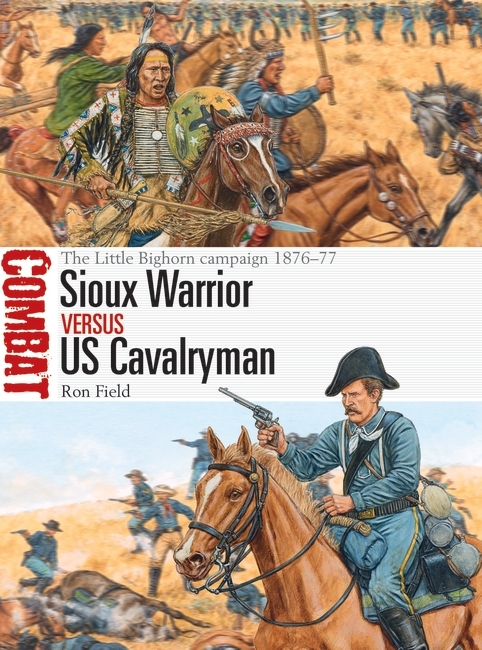

In today's blog post, we're speaking to Ron Field all about his latest Osprey book, Combat 43: Sioux Warrior vs US Cavalryman.

Q: What drew you to this conflict?

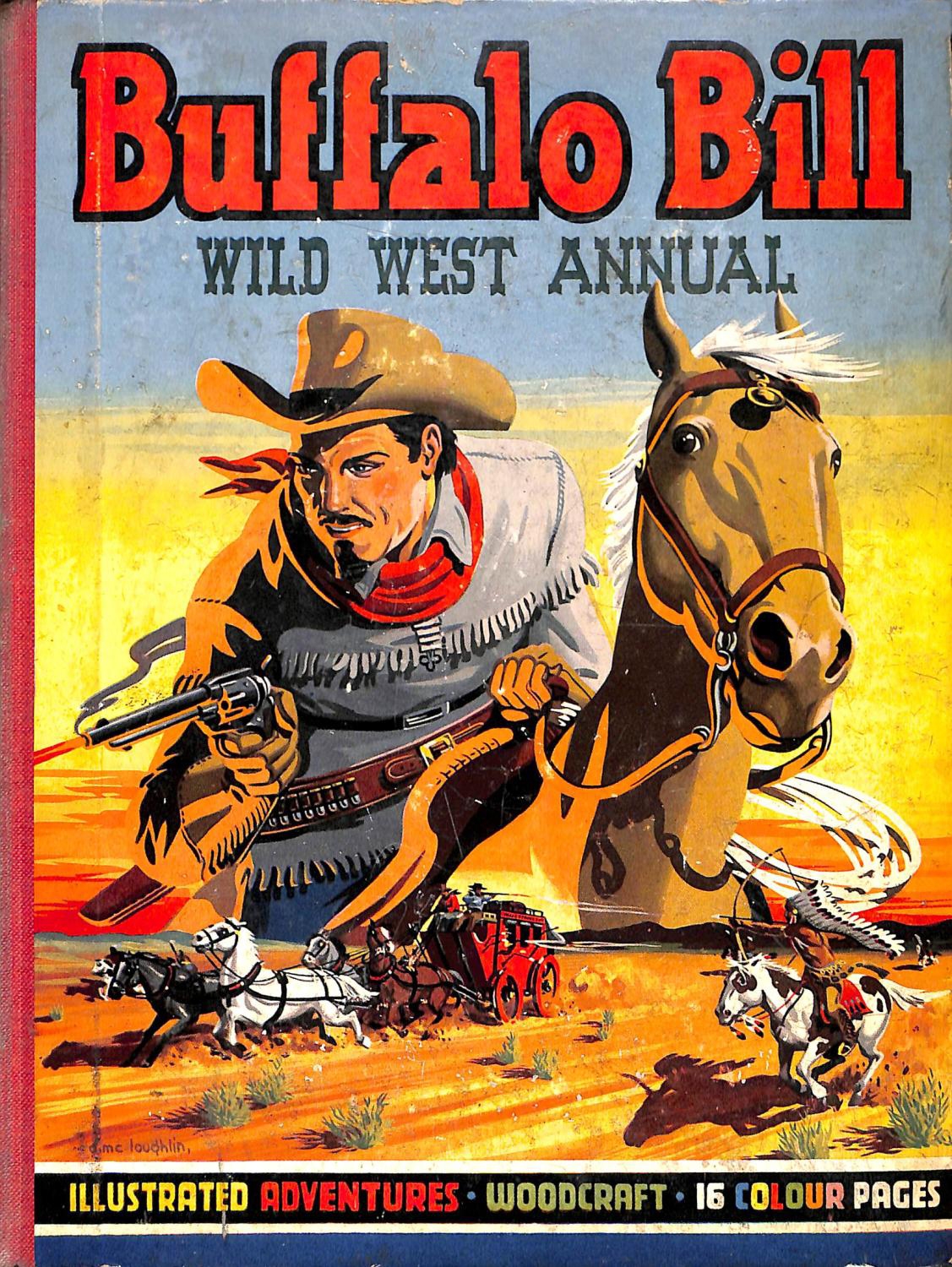

Since childhood I have been interested in the American West of the 1860s through 1890s. This was inspired when at nine years of age I received a Buffalo Bill Wild West Annual, published by T.V. Boardman, Ltd., as a Christmas present from a favourite aunt in 1950. The colourful stories by Arthur Groom and brilliant illustrations by Second World War veteran Denis McLouglin, including “Custer’s Last Stand,” captured my imagination and made me want to find out more about a captivating period in US history.

Q: What was the most interesting or surprising thing you found while researching Sioux Warrior vs US Cavalryman?

I was surprised to learn that although a contemporary source, namely the Army & Navy Journal, claimed that the ranks of the cavalry regiments involved in the 1876 campaign contained new recruits who were untested and improperly trained. However, an examination of the length of service of troopers of the 7th Cavalry at the Little Bighorn revealed that, of 576 men present at the battle, 471 had served over one year, 201 had served over six months, and only nine men had less than six months’ experience in the saddle.

Q: What new knowledge uncovered in this combat book is different from other books on the same topic?

The view in many books is that Medicine Tail Coulee was the northern most point that Custer, with only two companies of troopers, approached the banks of the Little Bighorn, but it is now believed that he attempted to reach the river at another ford about half a mile further downstream. As my text states, “Although Custer approached another ford about a half-mile farther downstream and probably saw the fleeing non-combatants, he turned back in the face of growing resistance from warriors who were furiously defending their women, children, and elderly."

Q: Why weren't repeating rifles more widely issued in the US army after their effectiveness had been demonstrated during the Civil War? Were there funding issues when the war ended?

The reason that the US army did not issue repeating rifles such as the Winchester in 1876 was partly due to cost. The lowest bidder in contracts was usually accepted by the Ordnance Department. There was also an extreme reluctance on the part of the army to innovate and adopt new weaponry. If Custer had wanted lever action rifles, he would have had to purchase them out of his own pocket. Some unit commanders did so during the Civil War but that was less common afterwards.

Q: Did US cavalry tactics consider rifle/carbine firing while on horseback viable, or were cavalrymen expected dismount and fire on foot when they needed to use their carbines?

The drill book used by the USarmy in 1876 was Lt Col Emory Upton’s Cavalry Tactics: United States Army – assimilated to the Tactics of the Infantry and Artillery, published in 1873. This instructed that dismounted skirmishing should be the main cavalry mode of engagement with the enemy. This required one of every four men, designated as a horse holder, to remain mounted and control the riderless horses of the three. Horse holders retired to a safe position in the rear. By dismounting and kneeling under fire, the remaining troopers presented a much smaller target for the enemy and could take aim much more accurately than if mounted. This tactic worked very well at certain points under Brig. Gen. George Crook during the battle at The Rosebud in June 1876. But at the Little Bighorn the attempts of Custer’s battalion to conduct this tactic without time or space to use horse handlers proved disastrous. As Sioux chief Red Horse recalled, Custer’s troops made “five different stands.” In each, combat seems to have begun and ended within about ten minutes. Another Sioux chief named Low Dog stated, “As we rushed upon them the white warriors dismounted to fire, but they did very poor shooting. They held their horses [sic] reins on one arm while they were shooting, but their horses were so frightened that they pulled the men all around, and a great many of their shots went up in the air and did us no harm. The white warriors stood their ground bravely.”

At Slim Buttes in September 1876, forces under Crook successfully followed that part of Upton's tactics which required a defensive perimeter be formed to fend off large scale mounted attacks. As a result, thousands of warriors under Crazy Horse were kept at bay with minimal casualties. Lessons had been learned by a more cautious commander which helped subjugate the remaining Sioux who opposed the US government.

Q: What are you working on now?

Latest projects keeping me busy include preparations for a Mexican American War contribution to the Campaign series. Also, in tandem with collecting period images, some of which I show-cased in my Osprey title Silent Witness: The Civil War through Photography and its Photographers, I am constantly preparing articles and features for inclusion in state-of-the art US publications such as Military Images and Civil War Navy Magazine.

To find out more, order your copy of Sioux Warrior vs US Cavalryman here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment