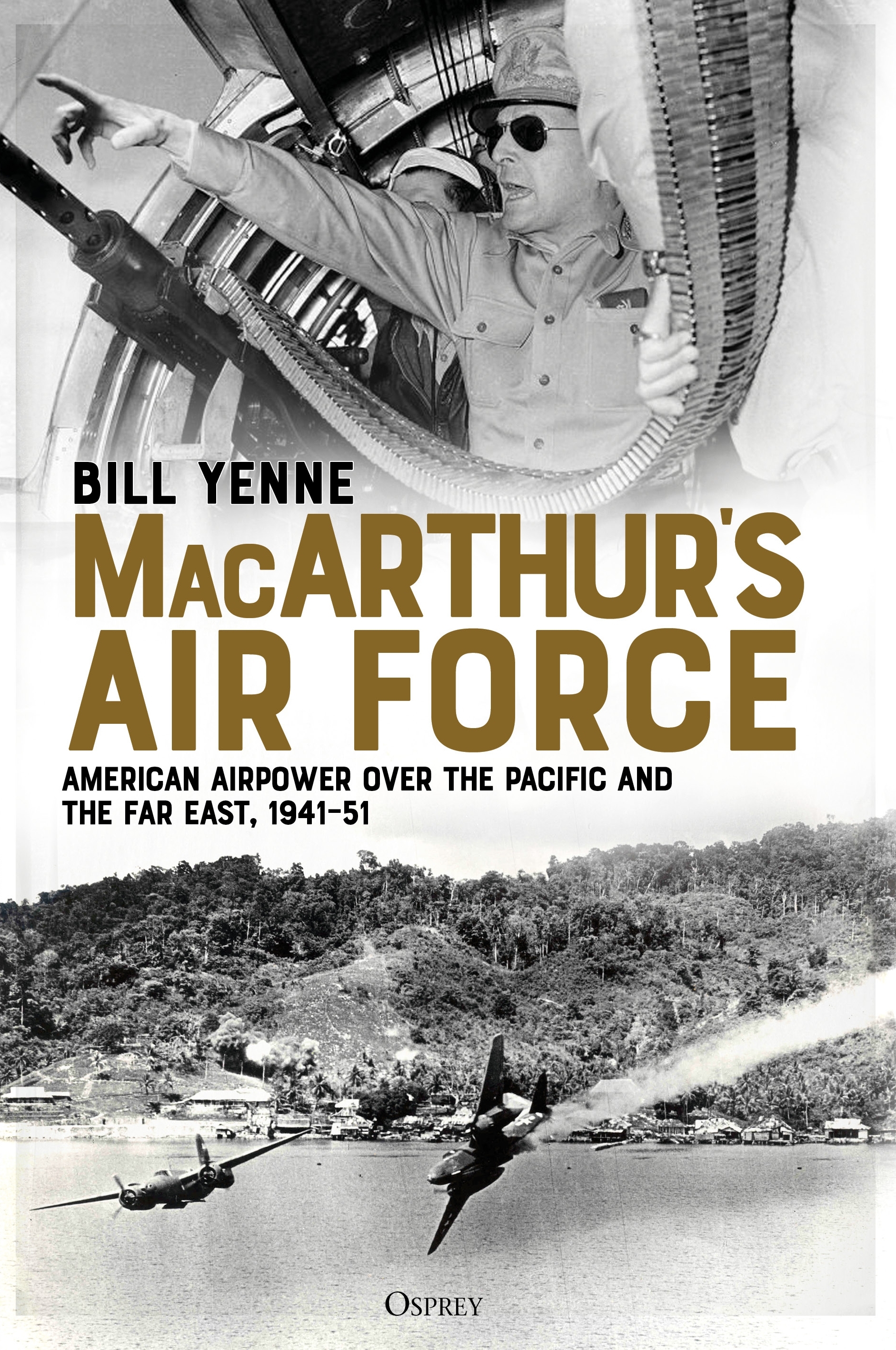

In today's blog post, Bill Yenne, author of MacArthur’s Air Force gives a brief overview of General Douglas MacArthur's association with airpower throughout his career.

General Douglas MacArthur was one of the towering figures of World War II, and of the twentieth century, but his leadership of the Far East Air Forces (FEAF) – the second largest air force in the USAAF – during the war is often overlooked. So too is his leadership role in a long series of other organizations which could each be called “MacArthur’s Air Force.”

MacArthur was at the end of his life when mine was just starting. I have always been interested in his career, and as an aviation and airpower author, I wanted to tell the story of his long association with airpower, beginning with the court martial of Billy Mitchell, and climaxing in the jet age over Korea.

Anecdotes discussing seminal early experiences with airpower for military officers during the first half of the twentieth century are often set on battlefields, on training fields, or aloft on memorable first flights. With Douglas MacArthur, this dramatic anecdote is set in a Washington DC courtroom in 1925.

The charismatic Billy Mitchell, both pioneer and prophet in the early years of American military aviation, was court-martialed for insubordination, but his theories on strategic airpower – later proven in World War II – were then on trial. Mitchell was convicted, but at least one vote was cast for acquittal, and it was that of Major General Douglas MacArthur.

Between that court-martial and the American entry into World War II, the term “MacArthur’s Air Force” could be applied to a series of entities within MacArthur’s chains of command:

(1) With MacArthur as Chief of Staff of the US Army (1930–1935), it was the US Army Air Corps.

(2) When he was field marshal of the Philippine Army (1936–1941), it was the Philippine Army Air Corps.

(3) In August 1941, as MacArthur was recalled to active duty to command US Army assets in the far East, his chain of the command contained the Far East Air Force (FEAF) of the USAAF.

(4) After the US entered the war against Japan, the remnants of the badly damaged FEAF were reconstituted as the Fifth Air Force of the USAAF.

December 8, 1941, in the opening Japanese air attacks against the Philippines, the FEAF was almost entirely wiped out. This story, like those of the subsequent American defeat in the Philippines, and of MacArthur’s escape, is well known. So too, are the stories of how MacArthur, as Allied commander for the South West Pacific Area (SWPA), rebuilt American power in the Far East.

Playing a pivotal role in the rebuilding of the Fifth Air Force component of the SWPA command was Major General George Churchill Kenney, who arrived in Australian July 1942 to assume command. He quickly made himself indispensable as one of MacArthur’s small coterie of right-hand men. In turn, this book looks at Kenney’s own small coterie of right-hand airmen – Ennis Whitehead, Ken Walker, Paul Wurtsmith, and the colorful, larger-than-life Pappy Gunn – and the roles they played.

For MacArthur and Kenney, this challenge of rebuilding was exacerbated by the global strategy adopted by Roosevelt and Churchill to direct the primary attention of the Allies to the war against Germany. Allied operations in the SWPA – from New Guinea to New Britain to Australia – had to be executed with less equipment and personnel than were available to units formed to fight Germany.

They did well with what they had. When they were sent medium bombers instead of heavy bombers, they developed the technique of attacking Japanese shipping using “skip bombing,” dropping a bomb at very low altitude and allowing it to skip across the water until it hit the side of a ship. This proved ideal for use in the SWPA, and became a signature tactic of Kenney’s airmen.

It was not just in the combat operations that the Fifth Air Force excelled. Kenney also pioneered tactical airlift, and in so doing, he turned MacArthur into an airlift activist. In September 1942, Kenney talked MacArthur into letting him transport the entire 128th Infantry to New Guinea. When Kenney did in hours what would have taken days by sea, MacArthur was sold on the idea, which was replicated numerous times.

MacArthur not only became an outspoken exponent of the idea of airpower, he made it the cornerstone of his strategic doctrine. Indeed, MacArthur’s legendary “island-hopping” strategy hinged on airpower. It was a strategic vision built upon a succession of air bases, each one captured from the enemy to support the capture of the next. Thanks to airpower, MacArthur’s forces could leap forward across the strategic map, bypassing enemy strongholds – such as infamous Rabaul – and letting them “wither on the vine,” because MacArthur’s Air Force could prevent them from being resupplied.

In 1942, MacArthur’s Air Force had been the Fifth Air Force alone, but by 1944, the Seventh and Thirteenth were added to form the Far East Air Forces (like the earlier FEAF, but now plural). By 1945, MacArthur’s Air Force had evolved from just a handful of about a dozen combat-worthy aircraft into a command possessing 4,004 combat aircraft, 433 reconnaissance aircraft, and 922 transports. It was the second largest air force in the USAAF after the “Mighty Eighth” in the European Theater of Operations.

Most histories of the FEAF end with the surrender of Japan, just as most biographies of MacArthur use that point in history to make the transition from the military to the political aspects of his role as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP). Yet the FEAF continued to exist during the period of the Allied occupation of Japan, performing a variety of missions, from transport to photoreconnaissance. Many of the FEAF bases established in the late 1940s under MacArthur are still part of the Pacific network of USAF bases today.

The final iteration of MacArthur’s Air Force came in 1950 with the start of the Korean War when MacArthur himself became Commander in Chief of the United Nations Command. His FEAF, especially the Fifth Air Force component, shouldered almost the full load of combat air operations for the UN during the first year of the Korean War. When MacArthur left the Far East in 1951 – having been relieved of command for the same sort of outspokenness that got Billy Mitchell in trouble – his FEAF had achieved air superiority over the Korean peninsula, and they would maintain it through to the end of the Korean War.

As his appreciation of airpower evolved and grew, General Douglas MacArthur commanded a series of air forces, some better known than others, and I feel that it was time to discuss them all as elements within the broader historic context of his career.

To find out more, order your copy of MacArthur’s Air Force.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment