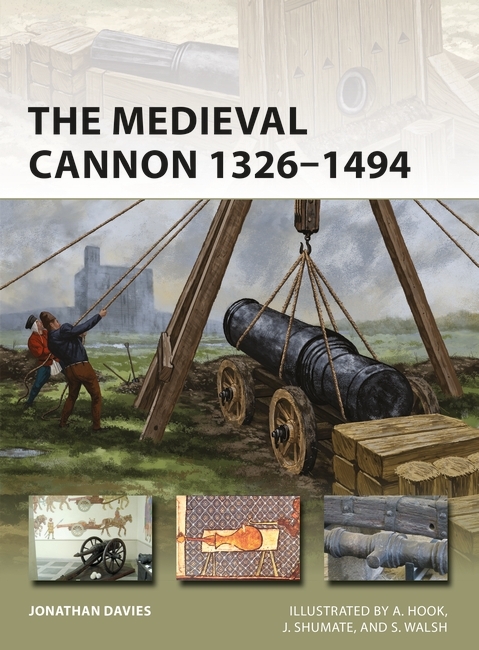

On today’s blog post, The Medieval Cannon 1326–1494, the author Jonathan Davies, recounts his inspiration, experience and mistakes writing the book.

What I didn’t know I didn’t know (with an apology to Donald Rumsfeld)

When I started writing the text for The Medieval Cannon 1326 –1494, I did not realise how little I knew. I knew what I knew and I had a fairly good idea of what I knew I didn’t know but there was an awful lot that I didn’t know I didn’t know. The finding out of this entirely new stuff was probably the most enjoyable part of the process.

Sometimes what I discovered was a matter of factual detail, such as the use of clay and glass projectiles. Sometimes it related to manufacturing techniques, the effective ‘mass-production’ of guns from individual workshops or the widespread and unexpectedly early manufacture of cast-iron guns. Sometimes it was the new analysis of a campaign or a battle.

If there was a lot to learn there were also quite a few fundamental points I wished to make. I – like most of my readers, I think – was brought up on a number of assumptions about medieval guns. Firstly, that the introduction of gunpowder weapons heralded a revolution in warfare that not only had an impact (I refuse to use the word impacted) on warfare but on contemporary social and political order. Secondly that most ‘medieval’ cannons were crude and posed as much a danger to their crews and innocent bystanders as their unfortunate targets. Thirdly, that most if not all ‘medieval’ guns were made from wrought iron, of hoop and stave construction.

Although I am an enthusiast for the medieval cannon (I own three replicas), I could find little evidence that it transformed warfare. It was intelligently integrated into existing patterns of warfare, replacing some weapons and augmenting others but it did not revolutionise warfare. It neither made fortifications obsolescent nor displaced the chivalry of Europe. I also fear that the current Military Revolution debate tends to ignore this period, which it should not, as it would give to the current discussion a sounder basis for its analysis.

Secondly, no-one would willingly crew a weapon that was as dangerous to himself as to the enemy (even the PIAT [The Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank] although pretty scary for its gunner was valued for its effectiveness). Medieval guns were proofed (stringently tested using very large charges) from the beginning, and much care was taken both to design weapons and manage their loading so as to maximise their destructive potential while operating them safely. There were undoubtedly disasters, as you may have noticed even our ultra-modern technology can go badly wrong. For example the brand-new Royal Navy super-carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth has just tried to sink itself from the inside! New technology is always problematic but our medieval predecessors were neither especially accident prone, careless, stupid or suicidal.

A study of documentary and pictorial evidence shows that cast-bronze guns were discovered, both very large and small, throughout this period. The assumption that early bronze ‘vase’ guns, were rapidly replaced by wrought-iron guns, which were in turn replaced by new large cast-bronze guns in an ‘Artillery Revolution’, is seriously flawed. If few bronze guns survive – often as underwater ‘finds’ or even more rarely as a result of historical serendipity (usually as trophy pieces) – this lack of examples is because bronze pieces could so easily be melted down and re-cast, again and again. The comparatively few survivors that we can study still demonstrate an extraordinary degree of technical competence in both casting and design.

Picture Research

My biggest mistake was not to start my picture research earlier. There were of course many other mistakes but this is the one I regret most. This is because I could have spent so much more time enjoying the wealth of contemporary images that are publicly available. The images I eventually chose were only a tiny fraction of what I would have liked to have used. It is not only the wealth of detail that they provide but that they are completed with wit and charm, bringing out the character of the age.

One of the best sources I found were the e-codices a collection of digitized manuscripts from all regions of Switzerland. The many images I chose from the Zurich and Berne Libraries derived from the e-codices collection. I would heartily recommend anyone to take a few hours or a lifetime studying the wealth of material contained there.

How The Mole got his Pockets

One of the reasons why I chose to choose this topic can be traced to my best loved childhood book, How The Mole got his Pockets. It was about a mole who, although he had found many things underground, a marble, mirror, safety pin etc., had nowhere to put them. With the assistance of many other animals and insects, flax was grown, linen woven, cloth cut, sewn and dyed. The mole was eventually provided with a magnificently blue pair of dungarees, with many pockets. This has left me with a love of multi-pocketed clothing, an understanding of the principles of a socialist economy (one of the intentions of this East European pro-communist production) and a fascination with industrial processes and manufacture.

I love to see metal being worked either in forge or foundry, the drama, potential danger, and extraordinary skill of those who work with metal has always fascinated me. I tried in the book to do justice to the technical accomplishments of those engaged in the manufacture of artillery and gunpowder. Of equal interest was the interplay between developing technology and tactics. In this book I therefore devoted as much time as I could to the use of artillery at sea, in sieges and on the battlefield. It also caused anomalies where the new advanced technologies appeared to fail or where tactical lessons were forgotten or mistaken. This is especially true its first century – a period of rapid change. The only comparable period is the half-century or so between the Crimean War and World War One where technological development changed the nature of war and the relationship between the three principal arms.

What Next?

I am not entirely at a loose end at the moment. I have sent my latest project, a bronze cannon, to be proofed. It is a cast piece that is a reduced version of the octagonal bronze falcon gun displayed at Fort Nelson (xix-14). The Nelson falcon has the Lombardic style letter G cast around the touch hole, this is probably the initial of the Genoese gunfounder Gregorio I Gioardi. This and the octagonal form would date it to the end of the fifteenth century and beginning decades of the sixteenth. My son has now resolved the remaining problems relating to the carriage, its strapwork, bolts, rivets and the positions of the transoms. The carriage is based upon one of those captured by the Swiss from the Burgundians at the battle of Grandson 1476 and which is displayed at the Museum of Neuveville.

Middeleladercentret

For anyone interested in seeing the medieval world come to life, a visit to the Danish Middle Ages Centre is essential. The Centre, the brainchild of the historians Peter and Katerina Vemming, is a medieval town and harbour with buildings and ships meticulously reconstructed. It has a wide selection of full-scale siege machines including trebuchets and guns as well as a busy tilt yard for their daily tournaments. Most recently they have constructed a ‘war wagon’, impressive to its enemies and deafening for those inside.

The Centre specialises in the reconstruction of medieval technology including diving gear, bridging equipment and most recently a reverberatory furnace for casting bronze guns. I spent a fortnight every two years with my re-enactment group from 2008 to 2016 and loved it. It is easily reached from Copenhagen by the excellent Danish rail network. You must spend a full day there to appreciate the Centre properly.

Thanks

If I found out many new things and was provided with many new insights when writing, this was often due to the generous assistance that I received from historians, re-enactors and those unsung heroes, librarians. I have tried to record my thanks to them individually at the front of the book. They provided technical assistance, unpublished research material, photographs and invaluable advice. I was able to use only a fraction of what was provided and I hope that my summaries of evidence and analysis does not do them a disservice.

I would also like to thank Tom Milner my editor for guiding me safely through the project and to Samantha Downes who demonstrated the patience of several saints towards my somewhat eclectic choice of sources both ancient and modern.

The Medieval Cannon 1326–1494 publishes today. Get your copy here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment