On the blog today, Nierstein and Oppenheim 1945 author Russ Rodgers looks at the events leading up to the crossing of the Rhine, the subject of his latest book.

The concept of airmobile operations, that of using aircraft to serial lift troops into a landing zone, is typically associated with helicopters during the Vietnam War. And yet, just a few days before the Third U.S. Army crossed the Rhine River at Nierstein-Oppenheim, General George S. Patton, Jr. approved a daring plan put forward by his chief artillery officer to launch what would have been the first airmobile operation in history. The genesis for such an action lay in part with the fact that a command like the Third Army had several hundred light L-4 and L-5 reconnaissance aircraft as part of their assigned equipment. Though flown by Army Air Force pilots, these planes were assigned directly to ground force commands, even down to the division level, thus making them readily available to Patton.

The L-4 Grasshopper and L-5 Sentinel were light liaison aircraft similar to the ubiquitous Cessna 172 flown today. Both were military versions of civilian aircraft, the former developed by Piper and the latter by Stinson, and were used for both liaison and artillery directional spotting. Both typically could carry one pilot and a passenger, and both had the ability to take off and land on very short runways and grass fields. Indeed, during Third Army’s drive to the Rhine, many L-4s and 5s used German Autobahns as temporary airfields, and it was not uncommon for these aircraft to land and take off from an area no longer than a football field.

With this in mind, Brig. Gen. Edward T. Williams, Patton’s chief artillery officer came up with what seemed like a hair-brained idea. It was to pool almost all of the available aircraft to be used to lift one full infantry battalion over the Rhine and to land on flat fields on the opposite bank. By operating in three waves, most of an infantry battalion, along with their indigenous machine guns and light mortars, could be shuttled over the river to create a bridgehead. This airdrop would be quickly followed up by ground forces that would use assault boats and Navy LCVPs to cross the river, with the laying of several bridges by the engineers soon after.

Patton was anything but orthodox in his approach to warfare, and was always on the lookout for ways to mix things up. The plan delighted him from the start, and Company C, 2d Infantry Regiment of the 5th Infantry Division was tasked to test the idea out. A field was selected to the west of the Rhine River, and a number of L-4s and 5s were quickly assembled for the trial run. There was little time for refinement, as Patton had already direct MG Manton Eddy, commander of the XII U.S. Corps, to deploy the rest of MG Leroy Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division to make the crossing by boat. Because of the novelty of the aerial plan, it was decided to use it as a backup if the waterborne landing was stiffly opposed and failed.

When initially tasked to make the Rhine crossing, Gen. Irwin was somewhat stunned. His division had already led the crossing of over 20 major rivers in the drive across France, and thus his men were obvious experts in such operations. But no reconnaissance of the opposite bank had yet been done; they could only rely upon Patton’s intelligence chief, Col. Oscar Koch, for any knowledge of what lay to the east of the river. Koch’s assessment had been straightforward: the Third Army had knocked the German Army back on its heels, yet in just a few days several divisions would arrive in the area to block any Rhine River crossing. If Patton’s men were to cross the Rhine with the least amount of bloodshed, it had to be at once.

Of course, Patton had other motivations than simply beating the German Army. The Allies had already planned to have Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group cross the Rhine on 23 March, and Patton was focused on beating him across. For any other to cross the Rhine before Montgomery was not part of “the plan” developed by Gen. Eisenhower and his staff. Even the capture of the Remagen bridge by Hodges’ First U.S. Army through the supreme commander’s staff into a tizzy, prompting Gen. Omar Bradley to ask if they wanted them to “pull back and blow it up?”

But Patton had his own ideas, and with tacit approval from Bradley, slipped a few battalions of Irwin’s 5th Infantry boys across the river on the night of 22 March, beating the British field marshal to the punch. Resistance was light, and as daylight approached it was decided to scrub the idea of the airmobile landing as both unnecessary and too risky, as the Luftwaffe had begun to ramp up their operations in the area in a desperate attempt to slow Patton’s push across the Rhine.

While not a significant theorist about mobile warfare, Patton was certainly one of its best practitioners. And when given the chance, he was willing to try out novel ideas, not only to give his men an edge over the enemy but also to boast the morale of his own troops, showing them how they could meet their mission’s goals while still being innovative and aggressive. Though the airmobile operation was ultimately canceled, it is possibly the first such operation ever to have been planned in warfare.

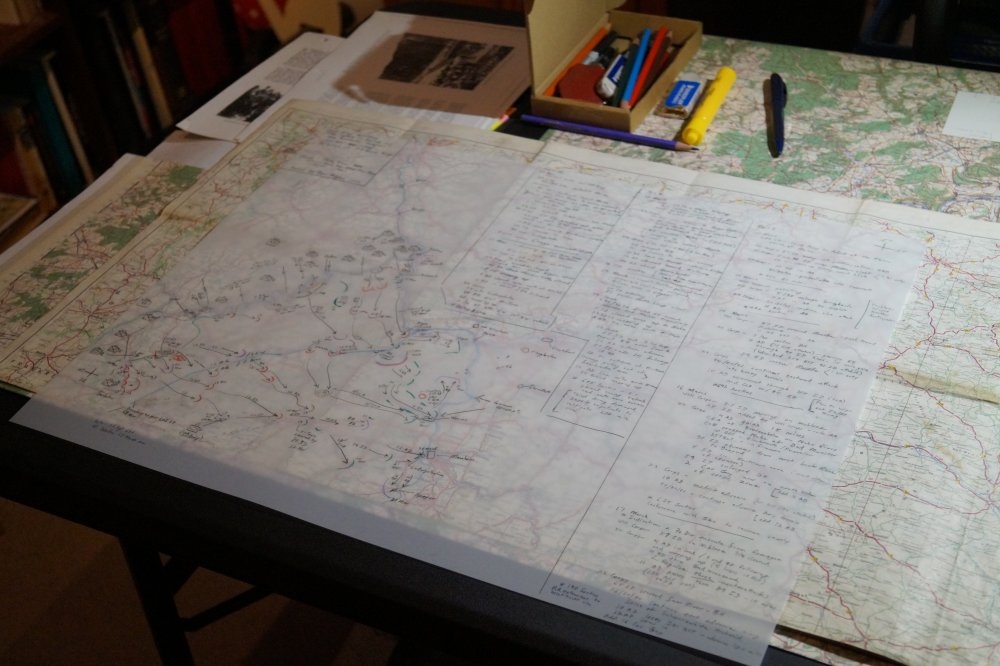

Developing the course of the battle and its appropriate maps is a matter of tracking the movement of units based on their after action reports and interviews with key participants of the action. One of the most effective ways to do this is to create an overlay of thin paper or vellum and using a map of the appropriate era, in this case a U.S. Army map made in 1943. Timelines are created and then plotted on the overlay. Simply put, this is nothing less than serious, hard work, and shortcuts are rarely as effective. Photo by Russ Rodgers.

Two photos of Frei-Laubersheim, then and now. The black and white photo shows LCM landing craft, capable of carrying an M-4 Sherman tank or two light M-5 Stuart tanks being transported towards the Third Army’s crossing site at Nierstein-Oppenheim. The photo taken in 2019 shows that the course of the road has been altered. Today it is about 20 meters to the right of the photo, the path of the original road now occupied by a house. The identifying landmark is the long red-roofed storage building. The cobblestone of the original road appears to have been laid after the war. Black and white photo, U.S. Army Signal Corps. Color photo by Russ Rodgers.

The Helen Keller School near Königstädten. The soccer field was the location of the small forester’s house where Generalmajor Siegfried Runge set up his headquarters in its cellar. Runge was in command of a scratch formation that held the east bank of the Rhine River opposite Nierstein-Oppenheim. He was mortally wounded very close to the forester’s house by a sudden American artillery barrage while attempting to organize a counterattack against Patton’s bridgehead over the river. Photo by Russ Rodgers.

Nierstein and Oppenheim 1945 is available to preorder from the website now.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment