Today on the blog we celebrate the publication of Peace, War and Whitehall: A Memoir by Field Marshal Lord Guthrie with an extract from The Welsh Guards chapter.

A family Regiment that has given me so much over my life.

I am proud to be a Welsh Guardsman. I joined the Regiment in 1959, and when I said farewell to regimental soldiering just over 20 years later after my time as commanding officer ended, it was a dispiriting moment. The Welsh Guards had become a second family. They gave me the lasting gift of friendship. They taught me how to lead.

There are many fine regiments in the British Army with proud records, but there is no better soldier than a well-led Welsh Guardsman. There is a healthy rivalry in the British Army, and army contemporaries would fiercely defend their own regiments. I would respond, and I believe this to be true, that to understand the formidable fighting spirit and character of the Welsh soldier, you only have to look at the Welsh rugby team. On their day, with their tails up and the Welsh hwyl focused, they are unbeatable. The Welsh temperament may be mercurial and things can go awry pretty quickly, but they respond well to a steadying hand and consistent leadership. The officer who shouts, or who is susceptible to histrionics and is inconsistent in his personal dealings, will fail.

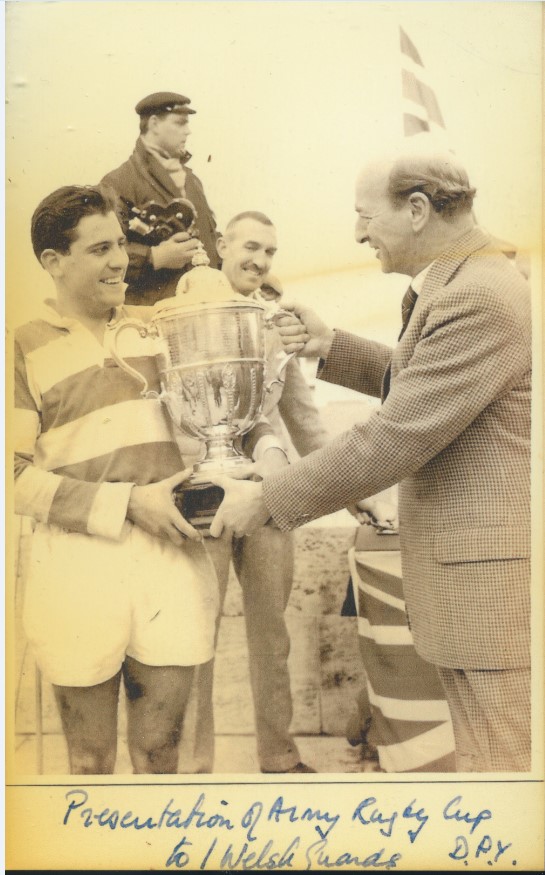

Being awarded the Army Rugby Cup by General Sir David Peel Yates. The Welsh Guards won the cup 1962-64.

My two years at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, from 1957 to 1959 taught me a good deal, except for practical experience. The rigours of my Harrow schooling had stood me in good stead. I smile when I read of some former public school pupil who ends up doing ‘time’, remarking that prison was really quite manageable if you’d been to an English public school. I did not find Sandhurst too taxing, but it gave me a sense of where my strengths and limitations lay. I made many good friends, a number of whom went on to the highest reaches of the army. I played for the academy rugby team and became a much better horseman. I developed a healthy regard for Guards non-commissioned officers who more or less ran the place and took a genuine pride in educating and training Britain’s future officers.

Harrow vs Wellington, 1957: Simon Clarke from Wellington, who later played for England, making his break. Robin Butler (later Lord Butler of Brockwell, Cabinet Secretary and Head of the Home Civil Service) on my left.

There was time for fun as well. I took great delight in running the gauntlet of returning to Sandhurst before first parade after visits to London to attend deb parties, or see my girlfriend in my beloved Ford Anglia. On the night before the Passing-Out Parade, this nearly saw the end of my army career before it had started. I had returned to Sandhurst in the early hours with a contemporary and good friend, John Wilsey. To our dismay, we found the doors locked to our college. John, who went on to become a four-star general with a flair for covert operations, spotted a route to our rooms up a couple of drainpipes and along a thin ledge to an open window. My parents, none the wiser for the early-morning escapade, beamed with pride as I was commissioned in the Welsh Guards.

I have never been a great admirer of Napoleon, though I am sympathetic to his much-quoted riposte: “I know he’s a good general, but is he lucky?”

On joining the Welsh Guards, and in my formative years in the Regiment, I was indeed lucky. I served under some fine commanding officers. They had all conducted themselves with courage and distinction in the Second World War.

I think it was because of this wartime experience that they went out of their way to educate young officers through personal example. After all, they had been young officers in the war. Nobody stood on ceremony then. Everyone, whatever his rank, was part of a common endeavour.

All the Regiment’s senior officers were different characters and all had different attributes, but I learnt something of lasting value from each. Their willingness to talk to, listen to, and guide those under their command never left me. I was also fortunate in having an outstanding platoon sergeant when I took command of my first platoon of men. He was called Sergeant Bill Elcock. He was a proud Shropshire man, and I could not have asked for a better man to help me understand the men under my command and avoid the usual pitfalls that trip up young officers.

My desire for travel and the spirit of adventure was met early on. I had only been in the Battalion a few months when we were transported by air to Libya for Exercise Starlight One. We were part of 1st Guards Brigade, and the airlift was the biggest air transportation exercise since the war. Before Colonel Gaddafi’s coup d’état, Libya was ruled by King Idris I. The king had seen what had happened in Egypt when Nasser overthrew the monarchy. He saw the US and the UK as his insurance policy.

My admiration for the British Eighth Army in the Second World War’s North Africa campaign grew as I saw at first hand the conditions they had fought under. The heat of the day was gruelling, the nights glacial, the terrain a torment for a young officer’s map-reading skills. We finished the six-day exercise with a brigade dawn attack on the Jebel Akhdar, a mountainous plateau 3,000 feet up in north-eastern Libya.

What I did learn from the experience was how tricky it is to move troops to an assembly area within given time limits over harsh terrain. It was a useful lesson. The Guardsmen, most of whom had never been abroad, were pretty cheery throughout and even more so when they were given 24 hours’ rest and recuperation in Benghazi. As one Guardsman said to me rather laconically as we boarded the flight home, “Quite a bit more lively than Merthyr Tydfil on a Saturday night, and a few tidy women. Mind you, the beer wasn’t too swift.”

Order your copy today on the Bloomsbury website!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment