On the blog today Historian Anthony Tucker-Jones recounts the strange tale of Winston Churchill’s involvement with the tough Czech Legion in Russia.

Whilst Winston Churchill’s desire to intervene in the Russian Civil War is well known, what is not generally appreciated is his enthusiasm for employing Czech mercenaries. Thwarted by the international community, which after the First World War had no desire to be dragged into another major European conflict, Churchill sought other ways of backing the pro-Tsarist Whites against the Bolshevik Reds.

The 1917 Russian Revolution and subsequent civil war knocked Russia out of the First World War, denying the West a crucial ally. An alarmed Churchill warned that Lenin and his revolutionary Bolsheviks posed a far greater threat than the German Kaiser ever did. To the dismay of Prime Minister David Lloyd George, his newly appointed Secretary of State for War and Air – one Winston Churchill – became obsessed with saving Russia from the Reds. The reality was that the fractious Whites were just as brutal as their opponents, committing horrifying atrocities in the areas under their control.

Allied soldiers had been committed to Russia towards the end of the First World War and in the wake of the Revolution in an effort to keep the country’s ports open. These forces included 40,000 British troops. When Churchill attended the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, he made it his personal mission not only to get the Allies to maintain their presence, but also to escalate it. This was in clear defiance of Lloyd George’s wishes and those of American President Woodrow Wilson. Only France favoured propping the Whites up until such time as their armies could fight unassisted. In an effort to sway favour Churchill suggested that all conscripts sent to Russia be replaced with volunteers.

Quietly and with little fanfare the Secretary of State for War and Air sent enough weapons to the Whites to equip an entire army. He also urged full support for Admiral Alexander Kolchak, who was the leading White commander. Churchill set his sights on recruiting the tough Czech Legion, which had been formed from Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war to serve alongside the Russian army on the Eastern Front, to fight with the Whites.

The Czech Legion, some 40,000 strong, was slowly heading for Vladivostok in order to sail to Europe and a newly independent Czechoslovakia. It was well organised and disciplined, and crucially had taken control of much of the strategically important Trans-Siberian Railway. Operating from armoured trains, the Legion regularly defeated local Red forces. Churchill, inspired by the military opportunities on offer, reasoned, ‘Surely now when the Czech divisions are in possession of large sections of the Siberian Railway and in danger of being done to death by the treacherous Bolsheviks some effort to rescue them can be made’. Churchill knew from British intelligence that the Czechs were the only decent troops under Kolchak’s nominal command. His plan was that they would stay in Russia until such time as Kolchak could replace them with newly trained Russian troops under the auspices of British officers.

The Czechs in the summer of 1919 helped spearhead a push on Moscow, while British and Russian troops marched south from Archangel to link up with them. This grandiose pincer movement failed miserably when the Russian forces supporting the British mutinied. The Red Army counterattacked Kolchak and he was driven back. Churchill then urged the Czechs to join the Allies at Archangel. If they captured Moscow they could go home via a much shorter route, but they declined. Once war broke out between the Bolsheviks and newly independent Poland and Ukraine, the Czechs feared for the future of their homeland and were desperate to leave Russia. Although the Poles triumphed over the Red Army outside Warsaw, by 1920 the Whites’ fortunes were waning thanks in part to a lack of co-ordination. The Czechs turned east.

At Irkutsk the Czechs handed over Admiral Kolchak and all their loot to the Bolsheviks in return for safe passage to Vladivostok. Their remarkable odyssey covered 15,000 miles and lasted two years. Churchill wrote, ‘The pages of history recall scarcely any parallel episode at once so romantic in character and so extensive in scale.’ Thus ended the exploits of Churchill’s Czech mercenaries. He held Lloyd George responsible for their failure to turn the tide of the Russian Civil War. Understandably the Prime Minister was stung by this accusation. ‘You proposed the Czechoslovaks should be encouraged to break through the Bolshevik armies and proceed to Archangel,’ Lloyd George said to Churchill. ‘Everything was done to support your proposal … Still you vaguely suggest that something more could have been done and ought to have been done.’ To his dying day Churchill felt an opportunity to change the course of history had been thrown away. As for the emerging Soviet Union it never forgave foreign meddling in Russia’s domestic affairs, least of all the warmongering Churchill.

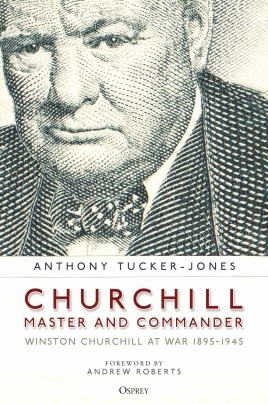

Anthony Tucker-Jones is the author of Churchill Master and Commander: Winston Churchill at War 1895–1945 published by Osprey.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment