On the blog today, author Gavin Mortimer takes us through Operation Rimau for his new book Z Special Unit: The Elite Allied World War II Guerilla Force.

Where would historians be without the internet? It has made life so much easier in so many ways. Archive documents that are digitalized and available to view online, for example, were a vital lifeline during the last two years when libraries and museums were closed for months on end.

Thanks to the internet I was able to make contact with the last surviving participant in Operation Rimau, the tragic Z Special Unit operation in the autumn of 1944 that resulted in the deaths of 23 men, including Ivan Lyon, the leader and inspiration of Z Special Unit.

I tell the story of Operation Rimau (Malay for ‘tiger’) in Z Special Unit: The Elite Allied World War II Guerrilla Force.In the course of my research in 2020I came across an interview housed in the Imperial War Museum with Michael Tibbs. Curses! This was one interview that hadn’t been digitalised and with the museum shut until further notice I simmered with frustration. I knew Tibbs was relevant to Operation Rimau because in the IWM’s brief biographical notes it mentioned that he had served as an officer on the submarine HMS Tantalus.

HMS Tantalus, seen here in Plymouth Sound in 1948, was named after the mythological Tantalus, son of Zeus. (Author’s Collection)

Tantalus had been instructed to collect the Z Special Unit commandos from the Indonesian island of Merapas in November 1944 on their return from a patrol in the Malay Archipelago.

The interview with Tibbs had been recorded in 1989 so I googled his name out of curiosity, on the off chance I might find a couple of snippets of information, perhaps a Royal Navy obituary. Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

To my astonishment up came a report on the BBC News’ website about a naval veteran who felt ‘very fortunate’ to have been one of the first people in the UK to receive a coronavirus vaccine. The 99-year-old’s name was Michael Tibbs. ‘I hope everyone will fall in and have it. I think it will make a lot of difference to everybody,’ he told the Beeb.

Next stop was the online BT directory enquiries and once I was confident I had the right ‘Tibbs’ I wrote a letter. A few days later Michael and I were exchanging emails, and he was generously answering some questions about Operation Rimau. A copy followed of his excellent war memoir, Hello Lad, Come to Join the Navy? in which Michael described his three years’ service on cruisers and destroyers in the Mediterranean, Atlantic and Arctic before joining Tantalusin the summer of 1943. The chapter of most interest to me recounted Michael’s minor role in Operation Rimau.

The Tantalus sailed from Western Australia on 16 October, 1944 on its sixth war patrol under the command of Lt Commander Hugh ‘Rufus’ Mackenzie, DSO. It would become an epic patrol that covered 11,600 miles and lasted 51 days.

Hugh ‘Rufus’ Mackenzie, commander of HMS Tantalus, seen here during the war, was a charismatic officer who inspired his crew. (IWM A 10254)

Once the submarine reached its operational area, Tantalus patrolled the waters off Borneo and Malaysia and sunk two vessels in three weeks. Tantalus wasn’t always the hunter; on one occasion the sub was depth-charged by two Japanese destroyers and for two hours they played cat and mouse at a depth of only 50ft. ‘I thought it was the end,’ reflected Tibbs. ‘But thanks to Rufus, it was not.’ Mackenzie barked orders with cool precision so that the submarine kept just ahead of the falling charges.

On 11 November the Tantalus launched a surface attack against the Pahang Maru and captured nine crew and a Japanese soldier. (Author’s Collection - Courtesy of Jeremy Chapman)

Tibbs celebrated his 23rd birthday on 21 November, just as Tantalus neared Merapas to fulfil its rendezvous with the Rimau commandos. As a birthday treat, Tibbs asked Mackenzie if he might accompany the two Z Special Unit soldiers whose task it was to canoe to the island to collect their comrades.

’I had to remove all badges of rank, all identity disks and everything like that and wear something very dark,’ recalled Tibbs, who complied with the instructions, cutting off an end of his scarf to use as a cap comforter. He was also given a cyanide capsule, for use ’to avoid you being captured and questioned.’

Perhaps the mention of the suicide pill – standard issue to all members of Z Special Unit – unnerved Mackenzie, for he changed his mind and ordered his lieutenant to remain on board Tantalus. ‘The risk,’ Tibbs was informed, ‘was not justifiable’.

Tantalus spent 21 November reconnoitring Merapas from below the surface, coming in as close as 1,000 yards. ’Nothing suspicious was seen but there were no signs of the party,’ wrote Mackenzie in his report. That evening the two soldiers, Englishman Walter Chapman and Australian Ron Croton, paddled ashore in a canoe, laden with compo rations and a silent Sten gun each.

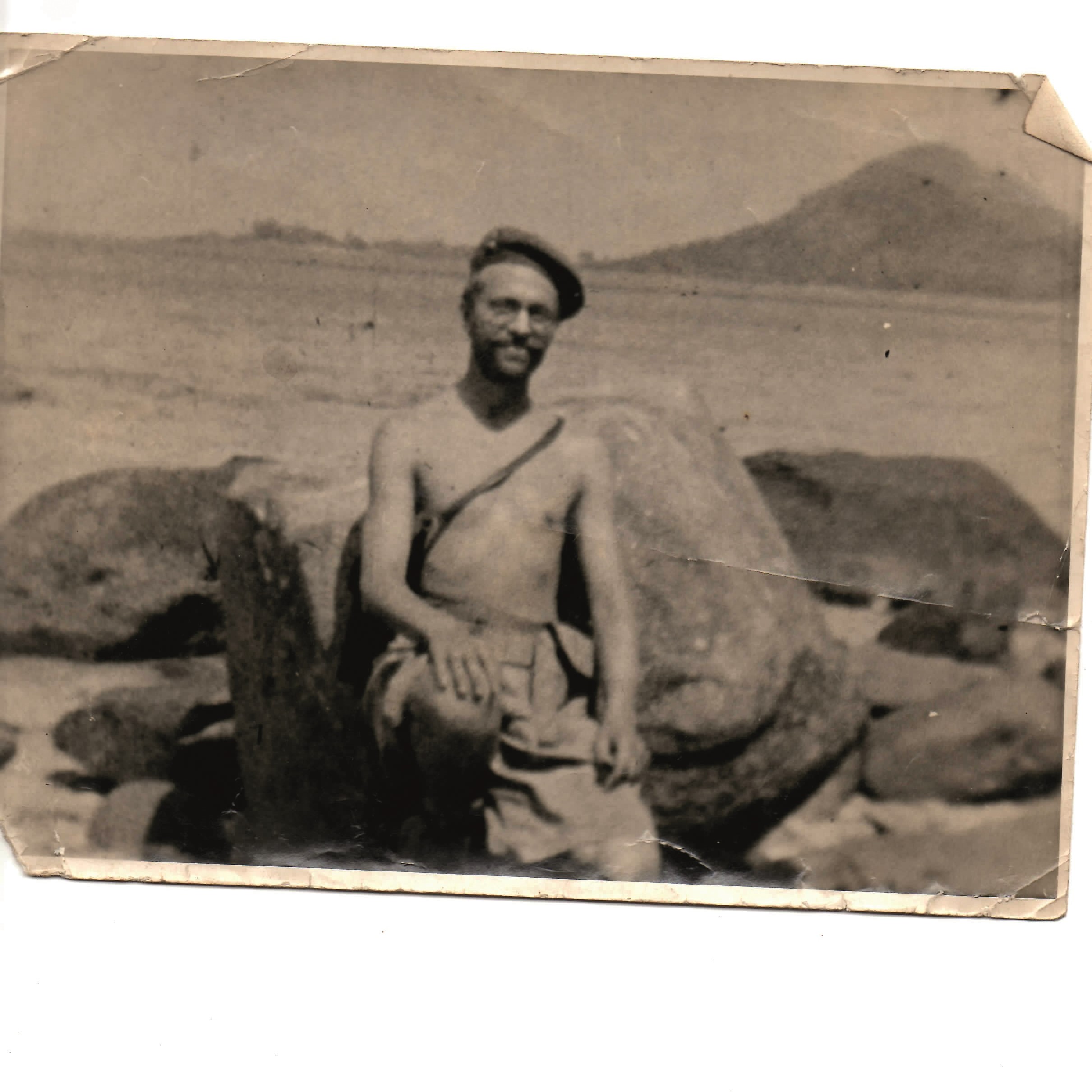

Walter Chapman on Merapas as photographed by Ron Croton, a picture probably taken from the east coast looking west, with Wild Cat Hill in the background. (Author’s Collection - Courtesy of Jeremy Chapman)

Walter Chapman on Merapas as photographed by Ron Croton, a picture probably taken from the east coast looking west, with Wild Cat Hill in the background. (Author’s Collection - Courtesy of Jeremy Chapman)

They returned the following evening with grim news. They had encountered none of the Z Special Unit men; they had certainly been on the island but they had departed, in some haste evidently, for Chapman and Croton had discovered half-eaten tins of food and discarded chocolate wrappers next to lean-tos. They also found a couple of empty packets of Three Castles cigarettes, the brand smoked by Z Special Unit. It was, as Chapman told Tibbs, ‘like the ship Mary Celeste’, the American merchant vessel, discovered adrift in the Atlantic in 1872 having been hurriedly abandoned for no apparent reason.

In the 1990s controversy erupted over Mackenzie’s decision to prioritise sinking enemy vessels over rendezvousing with the Z Special Unit party on Merapas. Australian historians accused him of negligence, a charge that was repeated in The Times in June 1994. Mackenzie rebutted the accusation in a subsequent letter to the newspaper. ‘I deny strongly that I either “failed to obey” or “ignored” my orders in regard to Tantalus’s part in the operation,’ he wrote. ‘On the contrary, these were very much in the forefront of my mind throughout that patrol.’ Mackenzie then explained that the Japanese had raided Merapas at the start of November, killing two of the commandos and prompting the rest to flee in canoes and small local boats. It was therefore irrelevant to argue about the date of Tantalus’sarrival off the island.

Michael Tibbs told me that he has never wavered in his belief that Mackenzie executed his instructions entirely satisfactorily, and it angers him that his captain’s reputation was traduced in the last years of his life. I agree.

The operational order of Mackenzie stipulated he was to sink enemy shipping with the submarine’s seventeen torpedoes and collect members of the Rimau party. The order, signed by L.M Shadwell, captain, Eighth Submarine Flotilla, was unambiguous in Mackenzie’s chief task:

‘The commanding officer HMS Tantalusis responsible for the safety of the submarine which is to be his first consideration and has discretion to cancel or postpone the operation at any time.’

Michael is justifiably proud of his wartime service, particularly his time with Tantalus. For my part, I am proud that on receiving a copy of Z Special Unit: The Elite Allied World War II Guerrilla Force he commended me for its detail and accuracy. For any historian praise is most gratifying when it comes from someone who was actually there.

Lockdown has so far prevented my meeting Michael in person but we have fixed a day in June to finally rendezvous. I am looking forward to shaking the hand of a very brave man.

If you enjoyed today's blog post, find out more about Gavin's book here

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment