Early on the morning of 16 November 1941, David Stirling and 54 men belonging to L Detachment, Special Air Service (SAS) Brigade, were flown from their base at Kabrit in Egypt to Bagush, 300 miles west. The RAF put their officers’ mess at the disposal of the SAS while Stirling reported to the nearby Eighth Army HQ.

There he was presented with the meteorological reports for the next 24 hours; they were grim. A storm was brewing and strong winds and heavy rain were predicted. Brigadier Sandy Galloway, Brigadier General Staff of Eighth Army, warned that a parachute operation would almost certainly end in disaster, especially as it was a moonless night. In addition, the drop zone was what the locals called hammada, a hard, stony surface. He advised Stirling to cancel the operation, but left the decision in his hands.

It was an agonising choice for Stirling. The SAS had been raised three months earlier, the 66 volunteers recruited from the commandos, units that had endured a frustrating period in the Middle East as countless operations were cancelled. He knew another cancellation would be bad for morale, but what if the weather reports were true and they parachuted into Libya to raid enemy airfields in the teeth of a terrible gale?

What David Stirling would have given to have his big brother to turn to at this excruciating moment. His counsel would have been invaluable. But Bill Stirling had been summoned back to Britain a fortnight earlier. His departure left David distraught. In a letter to his mother a few days later, David said that he hadn’t felt so homesick since boarding school and he expressed how sad he was to see Bill go.

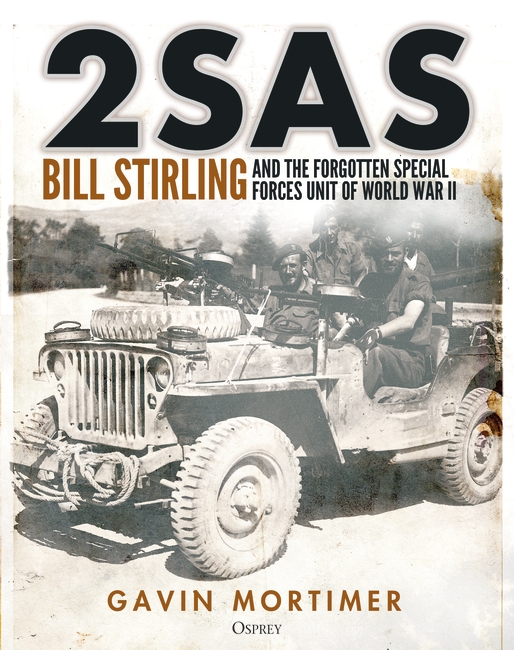

As I explain in my new book, 2SAS: Bill Stirling and the forgotten special forces unit of World War II, David relied on his brother emotionally and intellectually.

Far from being the sole founder of the SAS, David had leaned considerably on the experience and expertise of Bill. At the time that the SAS came into being, the joke in Cairo was that SAS stood for ‘Stirling and Stirling’. The brothers shared a flat in the Egyptian capital with a third brother, Peter, who worked at the British Embassy. One of Peter’s colleagues at the Embassy was Charles Johnston, who was a frequent lodger at the flat as did Charles Johnston. Post-war, he recalled how David and Bill ‘had acquired military fame in the Middle East as founders of the Special Air Service’. Believing that the regular army was too stiff and regimental, continued Johnston, the pair succeeded ‘in creating an entirely new force in their own image: buccaneerish, casual, tough, brave, fantastical and utterly irregular’.

A year before the creation of the SAS, Bill had been the driving force behind the formation of the Special Training Centre in the north-west of Scotland, colloquially known as the Guerrilla Warfare School, through which passed in the summer and autumn of 1940 hundreds of raw commando recruits. One of them was Bill Smallman, who recalled practising amphibious landings on the nearby islands of Rum and Eigg during his instruction at Lochailort. He described it as an excellent course, and he graduated ‘ready to kill’.

The course concluded with a challenging –48-hour march across rugged and difficult terrain. The actor David Niven remembered that after weeks of ‘running up and down the mountains of the Western Highlands, crawling up streams at night, and swimming in the loch with full equipment, I was unbearably fit’.

Bill had been inspired to set up the Training Centre after the failure of a special forces operation in Norway in April 1940. He and five other men from Military Intelligence Research, known as MI(R), which later became Special Operations Executive (SOE), had been instructed to land on Norway and, with local partisans, attack German lines of communication as the main Allied invasion force attempted to gain a foothold.

But en route to Norway, the raiders’ submarine hit a surface mine and they were forced to return to Scotland. The whole experience had convinced Bill – who had read history at Cambridge in the early 1930s – that Britain was an amateur in the art of guerrilla warfare.

So valued was Bill Stirling by the War Office that he was posted to Cairo in early 1941 and he was soon headhunted by Lieutenant General Arthur Smith, the chief of staff, second only to General Archibald Wavell in MEHQ, in a role that was described as in the ‘personal service’ of Smith.

Bill was therefore at the nerve centre of the British high command in North Africa; David, on the other hand, spent much of the spring and early summer enjoying the high life in Cairo as one commando operation was cancelled after another.

Eventually the brothers pooled their intellectual and creative resources and produced a proposal for an airborne special forces unit. How did they get their idea into the hands of the Top Brass? Well, it was nothing like the entertaining yarn spun in BBC drama Rogue Heroes.

That series, like so many previous histories of the wartime SAS, sticks to the time-honoured tale that the SAS was the brainchild of dashing David Stirling. But that was a tale told by David in the 1958 book The Phantom Major, which was, as the saying goes, ‘based loosely on fact’.

As I write in my book, ‘The brothers were both strong-willed and outspoken but there the similarities ended. Bill was discreet but David was not; Bill was pensive but David was not; Bill was well-balanced but David was not.’

David was also an incorrigible attention-seeker, and his brother was not. When a group of SAS officers compiled the Brigade’s War Diary in late 1945, Bill Stirling was described as ‘a man from the shadows’.

I hope that 2SAS: Bill Stirling and the forgotten special forces unit of World War II will bring him in from the shadows. He deserves some limelight.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment