Those of you who purchased my book “Clean Sweep: VIII Fighter Command vs the Luftwaffe,” have seen that the cover very prominently features the fact that the Foreword was written by Brigadier General Clarence Emil “Bud” Anderson.

I was really happy when Bud agreed to write a foreword for the book, and really gratified that he read it (at age 101) and told me it was the best book he had read about his war; he particularly liked that the other side was there. That’s the kind of gold-plated compliment you keep close.

Bud died on May 17, five days short of his 103rd birthday. The family announcement read, “On 17 May 2024 at 5:29pm, Bud Anderson passed away in his home peacefully in his sleep surround by his family. We were blessed to have him as our father. Dad lived an amazing life and was loved by many.”

He did lead an amazing life, and he was loved by many. Including me.

Bud was a member of the 357th Fighter Group, known as “The Yoxford Boys” after Lord Haw-Haw “welcomed” them to England the day they arrived at their new base at Yoxford. Originally assigned to the Ninth Air Force, the 357th was to be the third group equipped with the new P-51B Mustang - and the third assigned to the Ninth Air Force, a tactical force. This finally caused a revolt by the leadership of VIII Fighter Command. General Kepner and his leading group commanders argued to Jimmy Doolittle that the P-51 ws the airplane they needed - it had the range to go to Berlin, and the performance to best anything the enemy could put in the air. Doolittle let Kepner make his argument to General Eisenhower, who had just arrived in England to take command of the Allied armies as Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force. Eisenhower agreed with Kepner, and ordered the transfer of the 357th to Eighth Air Force and that all future Mustangs arriving in England would go to VIII Fighter Command on a priority basis.

Bud first experienced combat on the group’s first mission, January 20, 1944. It was the largest force assembled to date of the American strategic air forces, with sixteen wings of heavy bombers – 1,003 B-17s and B-24s. The targets were the aircraft production factories in the Brunswick-Leipzig region, only 80 miles south of Berlin. The mission involved a flight of over 1,100 miles round trip, and the 357th would provide target support, along with the 354th “Pioneer Mustang” group. Led for this mission by the legendary Don Blakeslee, the 357th would cover the bombers over Leipzig. Light snow was falling when they took off, but the weather cleared by the time they crossed the Channel.

The Mustang at that time was not the reliable airplane it would become; the most prominent problem was engines cutting out (eventually solved by changing from Champion sparkplugs to British Lucas plugs for use with the lower-quality British avgas). Ninety-six P-5s of the two groups left England; by the time they were over central Germany, both groups were down to fewer than 40 Mustangs - the total force that would defend 900 bombers over the target.

The 357th’s pilots claimed their first victories when several Bf-109s jumped Lieutenant Calvert Williams’ 362nd Squadron flight. One overshot and Williams immediately opened fire, sending it down trailing black smoke. The 363rd squadron’s Donald Ross tangled with another pair of Bf-109s and shot down the wingman, but was so close behind that when it exploded, he was forced to fly through the explosion; his radiator was damaged by debris sucked into the belly intake. His Merlin engine quickly overheated and Ross was forced to bail out.

Flight leader Bud Anderson of the 363rd was fighting the cold in his cockpit when he spotted an Fw-190 4,000 feet below. He dived and came out 300 yards behind; the enemy pilot evaded with a split-S. Anderson followed. “I was determined I would go wherever he went, do whatever he did. I wanted a victory.” Suddenly, he felt an unexpected blast of cold air and looked up to see that the “coffin lid” of his canopy was lifting, separating from the side piece as the latch started to fail. It got worse as he went through 11,000 feet at nearly 500 miles an hour. Prudence finally won out. He pulled the throttle back, then nosed up into a climb and rejoined the group. Years later, he said, “Thinking about it afterwards, I realized I had come close to doing something unforgivably dumb.”

During the battles over Leipzig and Brunswick, 21 of the 941 bombers were shot down, while the escorts lost four. They claimed 61 enemy fighters shot down; Luftwaffe records admitted loss of 53 Bf-109s and Fw-190s, and 25 Bf-110s, better than U.S. claims. Only 362 German defensive sorties were flown, less than half the number expected.Doolittle had been prepared for the loss of 200; the results were better than their wildest dreams: four assembly plants in Leipzig had been hit hard. Overall losses were 2.8 percent.

On January 21, the bombers went back to Brunswick. Bud wasn’t on the flight schedule, but his brand-new P-51, the first of several named “Old Crow,” was flown by 1st Lt Alfred Boyle. Shortly after the group crossed into Holland, Bf-109s attacked, trying to get them to drop their tanks. Boyle’s flight went after them and he got on the tail of one in a wild dive. When he opened fire, the 109 shed parts and several hit his prop. He barely managed to bail out of the tumbling Mustang to become a POW. When Anderson learned that his new airplane had been lost, he pretended to be upset but later wrote, “By now I was getting pretty good at blocking out unpleasant distractions. I was developing a thick hide.”

Bud’s most memorable mission with the 357th Fighter Group was the one where he and Chuck Yeager managed to miss the group’s “greatest day of the war.”

January 14, 1945, would be remembered in the 357th Fighter Group as “Big Day.” It turned out to be the last big air battle against the Reichsverteidigung Geschwadern. The sky was crystal-clear over the Continent, perfect conditions to send 950 B-24s and B-17s from the 2nd and 3rd Air Divisions against synthetic oil factories and storage sites in northwestern Germany.

The 3rd Division’s bombers flew over Schleswig-Holstein just south of the Danish border, then turned toward Berlin, where their targets were in Derben, Stendal, and Magdeburg. The Yoxford Boys provided escort, positioned at the head of the bomber stream. Approaching Berlin from the northwest, they spotted enemy fighters ahead at 28,000 feet. The Fw-190s broke and dived away, pursued by the 363rd Squadron. The 362nd Squadron engaged the Bf-109s that belatedly dived into the fight.

Over the next 30 minutes, the enemy pilots demonstrated no lack of fight, being very good at evasive tactics. Despite their willingness to stick around and fight and their two-to-one advantage in numbers, the enemy pilots were no match for the experienced Mustang pilots, who claimed 56 destroyed for a loss of three, a new high score for a single group. In the battle, four pilots became aces.

Bud and Chuck Yeager had been assigned as spares for the mission, but when no one aborted, they broke away to spend their final mission touring Germany. Heading south, they made a low-level run through the Alps along the German–Swiss–Italian border, playing with their airplanes in the stark blue sky after dropping their tanks in a meadow and strafing them to start a fire. They were the last to return to base. Anderson’s crew chief, seeing the gunfire residue on “Old Crow,” asked him how many he shot down. When Anderson replied “none,” his crew chief related what had happened over Germany. Years later, Anderson said it still made him “sick” to remember how he missed the group’s greatest day.

Bud was born on January 13, 1922, in Oakland, Calif., and grew up in Newcastle, near Sacramento. He was fascinated by commercial airliners flying above his town, and his father, a farmer, treated him to a biplane ride when he was 7. “From that day on, I knew I wanted to fly,” he often said. He gained a pilot’s license in a civilian training program as a teenager, then, turning 20, he joined the Army’s air wing a few weeks after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

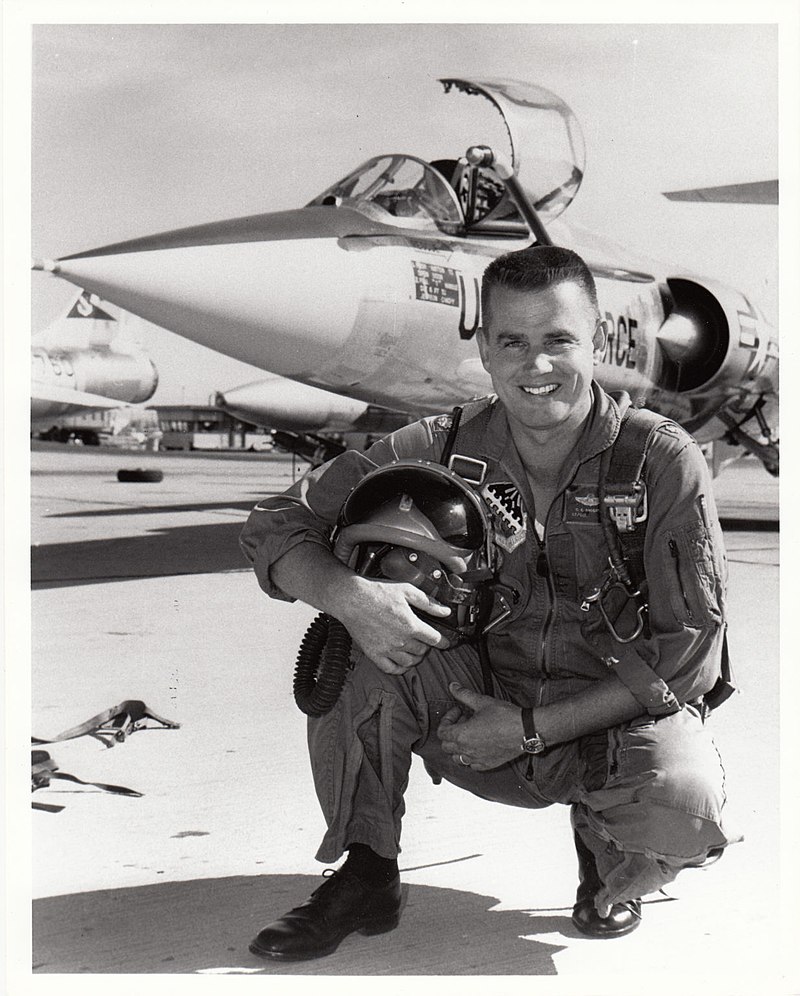

Eventually, as a Colonel, Bud commanded a wing of F-4 Phantoms in Vietnam. In the 1990s, he and Chuck Yeager made appearances at airshows together, each flying a restored P-51D in the markings of their respective wartime mounts.

Bud named all his Mustangs “Old Crow,” for his favorite brand of whiskey, while logging 116 missions totaling some 480 hours of combat without aborting a single one.

When World War II ended, Bud was a 23-year old Major. His decorations included two Legion of Merit citations, five Distinguished Flying Crosses, the Bronze Star and 16 Air Medals.

Bud’s lifelong friend Chuck Yeager said of him, “On the ground, he was the nicest person you’d ever know. But in the sky those damned Germans must’ve thought they were up against Frankenstein or the Wolfman. Andy would hammer them into the ground, dive with them into the damned grave, if necessary, to destroy them.”

Bud commanded a tactical fighter wing in the Vietnam War and flew 25 missions in an F-105 Thunderchief he named “Old Crow II,” flying bombing missions against the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Deciding to remain in the Air Force after the war, Bud became a test pilot at what is now Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio in the late 1940s and early ’50s. After retiring from the Air Force in March 1972, he was chief of test-fight operations for the McDonnell Aircraft Company at Edwards Air Force Base in California’s high desert.

In his 30 years of military service, Bud flew more than 130 types of aircraft, logging some 7,500 hours in the air.

For all of that, I remember the first time I met Bud, when he showed up at Planes of Fame to giv a talk on his career. For all the exhilaration of winning so many dogfights, Bud said he saw war as “stupid and wasteful, not glorious.”

The Air Force gave him an honorary promotion to Brigadier General when he celebrated birthday 100.

The best part of my “job” over all these years has been meeting guys like Bud and being privileged to have them call me “friend.”

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment