Introduction

In my opinion the achievements of the Czechoslovak Army, Air Corps and paramilitary forces before and during World War II have been underestimated by students of military history. This Osprey Men-at-Arms book is an attempt to give the Czechoslovaks the credit they deserve.

The official establishment date of the Czechoslovak Army was 28 October 1918, ten days before the Republic of Czechoslovakia declared its independence, but the Czechoslovaks had already earned a respectable military reputation during World War I by forming contingents in the French, Russian and Italian Armies, fighting the German and Austro-Hungarian Armies, the Czechoslovaks, however, shared the sad fate of the Poles in fielding units in the Austro-Hungarian Army who fought their own countrymen. Czechoslovak forces, united in 1918 in the Czechoslovak Legion, continued fighting the Russian Bolshevik Armies in Siberia until March 1920, when they were evacuated from Siberia to Czechoslovakia via Vladivostok.

The Czechoslovak Army gained a respectable military reputation in the Inter-War period 1920–1938. The Czechoslovaks built a strong industrially-based economy which allowed them to afford an Army which compared well technically with the best European armies, with a significant number of home-built Škoda tanks and mechanized vehicles. Like the British Army, the Czechoslovaks had completely mechanized their divisions by 1937, whilst the German Army was still operating horse-drawn transport units in May 1945. Czechoslovakia manufactured (and exported) its own artillery and small arms – indeed the standard British Army medium machine-gun was the Bren gun, a joint Czechoslovak–British (Brno-Enfield = Bren) venture. Only in aircraft was Czechoslovakia found wanting. Having developed a good range of aircraft in the 1920s, the Air Corps, which remained a branch of the Army and never formed an independent Air Force, was still operating obsolescent biplane fighters in 1939, long after its competitors had progressed to monoplanes such as the British Supermarine Spitfire or German Messerschmitt Bf 109.

The main weakness of the Czechoslovak Army lay in its social mix. In theory Czechoslovakia was a multinational state with Czech, Slovak, Sudeten German, Polish, Rusyn (Sub-Carpathian Ruthenia, actually Ukrainian) and Jewish minorities enjoying equal rights. In fact, the Czech majority dominated the Army and society, and the Czechs were accused of arrogance towards the minorities, particularly the Sudeten Germans, who resented the fact that their vote for union with Germany in 1918 had been ignored, and the Slovaks, who felt undervalued. These social fault-lines were to prove critical.

Czechoslovakia fractures

On 30th January 1933 Adolf Hitler became Chancellor (Prime-Minister) of the German Third Reich. Hitler was determined to unite all ethnic Germans in a pan-German state ruled by the Nazi Party (NSDAP). Hitler had first planned to annex Austria but in fact it was the Sudeten German leader, Konrad Henlein who moved first, creating the Sudeten German Home Front (Sudetendeutsche Heimatfront – SDH) on 1 October 1933. Henlein formed two paramilitary organizations to attack Czechoslovak troops and civilians on the borders. The Volunteer Protection Service (Freiwilliger Schutzdienst - FS) was formed 14 May 1938 as an internal security force and eventually comprising 60–70,000 men. On 16 Sep 1938 it was absorbed by the 41,000 strong Sudeten German Free Corps (Sudetendeutsches Freikorps), which waged a short cross-border war with Czechoslovakia 18 – 30 Sep 1938.

The Czechoslovak government already had three well-established paramilitary organizatioins. These were the Urban Police (Státní policie), Rural Police (Četnictvo) and Customs Border Guard (Finanční stráz - FS). On 23 Oct 1936 these formations, reinforced by Army reservists,

were formed into the 30,000 strong State Defence Guard (Stráž Obrany Státu - SOS), and valiantly defended the border districts against Henlein’s insurgents, forming an effective defence against the Sudeten Germans. The Czechoslovak Army undertook a full mobilization of its forces 23rd September 1938 and its generals were prepared to fight, but a week later, on 30th September, Prime Minister Jan Syrovy, himself a distinguished General, signed the Munich Agreement, agreeing to cede the Sudetenland to Germany, under the naïve assumption that Hitler would make no further demands on Czechoslovak territory.

This prompts the obvious question. Why did the Czechoslovak Army, a force with a proven record of combat, not defend the country against the German dictator? At this point it is worth mentioning that there seems to be an element of political calculation in the Czechoslovak character which may partially account for this. Whilst the Czechoslovak Army, supported by the SOS and probably civilian volunteers, constituted a formidable military force which had the advantage of being the defenders of home territory, this did not seem enough for the Czechoslovak government and Army to risk armed conflict. One clear factor was the attitude of Czechoslovakia’s neighbours. Despite being a communist state, the Soviet Union had an informal alliance with capitalist Czechoslovakia. Syrovy expected Stalin to send reinforcements to defend Czechoslovakia and was disappointed when this Soviet force did not materialize, a disappointment reinforced by the entirely predictable refusal of France and Great Britain to honour their treaty commitments to Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia was a democratic state and the Army was bound to obey its political leaders, even at the cost of the state’s destruction. Prime Minister Beneš refused to allow the Army to defend its native land, so the Sudetenland, which contained a comprehensive and modern ‘Maginot Line’ of concrete fortifications, fell to Germany with scarcely a shot being fired. However in May 1945 Beneš apparently looked at Prague, its buildings scarcely damaged by the War, and felt justified at having avoided a bloody conflict.

Only six months later, on 15th March 1939, German forces occupied Bohemia-Moravia (western Czechoslovakia) whilst Slovakia was given its independence and Subcarpathian Ruthenia was ceded to Germany’s ally, Hungary. Although Bohemia-Moravia was a Slav state it was heavily industrialized and Hitler believed that in time it could be absorbed into Germany. Many Czechoslovak officers were shocked at the inferior quality of the German Army equipment and weapons, and many must have wondered if Czechoslovakia should have surrendered so easily without a fight.

Czechoslovak Armies 1939-1945

From April 1939 small groups of Czechoslovaks escaped to Poland to join the Polish Army and, in September 1939, formed the 1st Czechoslovak Infantry Division of the French Army. The Division fought well in the Battle of France in 1940 but was unable to avoid the defeat of its French and British allies. Ironically the German Panzer forces were largely equipped with Skoda Tanks requisitioned by the Germans in March 1939. Czechoslovak forces escaped to Great Britain but only had enough men to form a battalion for action in North Africa. Meanwhile the 1st Czechoslovak Mixed Brigade trained in Great Britain from August 1940 to August 1944, when it finally saw action in the D-Day forces.

Czechoslovak Army troops in Western Europe enjoyed a good military reputation but there were simply too few of them to make a strong tactical impact on the battlefield. Czechoslovak volunteers in the Royal Air Force are however fondly remembered in the Czech Republic today with Sergeant Josef František as the top RAF ace during the Battle of Britain. There is no explanation for the fact that there were no Czechoslovak troops in the 10th (Interallied) Commando force but the Czechoslovaks contributed a large number of parachutists for SOE operations in Bohemia-Moravia, culminating in Operation Anthropoid - the assassination of SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich in June 1942, which was however judged counterproductive due to the large number of reprisals exacted by the Germans.

Many Czechoslovak Army officers who were unable, or unwilling, to continue resistance abroad joined resistance organizations in Bohemia-Moravia, but these units were heavily penetrated by German security forces and were not as effective as they might have been. The official Bohemia-Moravian force, the Government Army, enjoyed publicity out of all proportion to its military value, which was deliberately kept at a modest level by the Germans.

Czechoslovak forces on the Eastern Front were far more effective, as they enjoyed the support of the Red Army and were able to recruit respectable numbers of replacement troops from Czechoslovak, Slovak and Rusyn communities in the Soviet Union as well as captured Slovak Army troops. In May 1944 these troops were reorganized as the 1st Czechoslovak Corps in the USSR and fought creditably in August 1944 in the unsuccessful Slovak Insurrection and the hard-fought Battle of Dukla Pass, which allowed Czechoslovak forces to enter Czechoslovakia and liberate the homeland in May 1945. Meanwhile United States Forces under General Patton, which aimed to occupy Prague and perhaps claim Czechoslovakia for the Western Allies, were ordered by General Eisenhower to evacuate Bohemia-Moravia and turn Czechoslovakia over to the Red Army. Meanwhile heavy fighting continued in Prague until 11th May 1945.

After the end of hostilities the Czechoslovak population, disillusioned at the failure of the Western Allies to support them at Munich in 1938, turned to the Soviet Union for support, only to lose their democratic freedoms in the Communist coup d’état of February 1948. Many Czechoslovak servicemen who had fought with the Western Allies in World War II were imprisoned and it was not until 29th December 1989, when democratic Czechoslovakia was restored, that they were rehabilitated. Czechoslovakia had paid a heavy price for Munich.

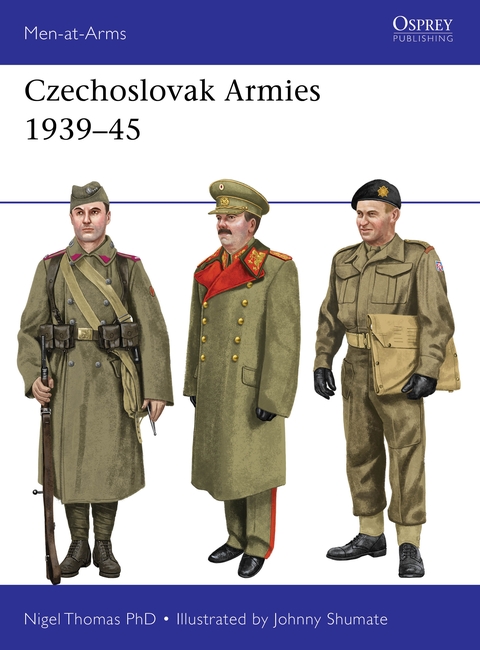

If you enjoyed today's blog post you can find out more in Czechoslovak Armies 1939–45

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment