Struck by lightning! Marcus Aurelius’ miracle of the rain, AD 174

One of the most remarkable scenes on Marcus Aurelius’ Column depicts a god of rain slaking the thirst of the Romans and granting them victory. Elsewhere on the column, we have scenes of enemies struck by lightning. In the very sparse surviving literary records of Marcus’ wars, however, the rain and lightning are combined into one moment. The historian Dio Cassius’ books are very fragmentary for this period – so much so, we are not even sure if he recounts the incident in book 71 or 72, but he tells us that when Marcus pursued the Quadi into their territory over the Danube, his army became surrounded and the enemy stopped attacking and was merely waiting for the Romans to expire from thirst. When the Romans seemed to be dropping from thirst and exhaustion, the Quadi and their allies attacked. At that moment, however, a downpour broke over the Romans and allowed them to slake their thirst. Dio tells us that ‘at first all turned their faces upwards and received the water in their mouths; then some held out their shields and some their helmets to catch it, and they not only took deep draughts themselves but also gave their horses to drink. And when the barbarians now charged upon them, they drank and fought at the same time.’

Now, this incident is complicated because later Christian writers record that it was their prayers which were responsible for this Miracle of the Rain. In AD 174, however, more than 150 years before Christianity would become the official religion of the empire, it is highly unlikely that they would have done so in any official capacity. What is more, Dio does record others taking responsibility too – a magician named Arnuphis with the legions for instance (the later excerptor of Dio refutes this). There was even a contemporary letter which claimed that the emperor thanked the Christians personally for their service. This letter is clearly a forgery (but it was a contemporary one) and it was accepted as genuine by Christian writers, such as Tertullian, writing only a few years later. Another story associated with the Miracle of the Rain is that, at the same time as the rain, a violent hail-storm and thunderbolts rained down on the Quadi and their allies (and only on the Romans’ enemies). Dio goes into detail: ‘Thus in one and the same place one might have beheld water and fire descending from the sky simultaneously; so that while those on the one side were being consumed by fire and dying; and while the fire, on the one hand, did not touch the Romans, but, if it fell anywhere among them, was immediately extinguished, the shower, on the other hand, did the barbarians no good, but, like so much oil, actually fed the flames that were consuming them, and they had to search for water even while being drenched with rain.’ This is all highly dramatic stuff. The association of the twelfth legion, called fulminata, or the ‘thundering’ legion with this incident is another complicating factor – that legion and its title date back to the days of Mark Antony in the later 1st century BC. Dio, however, (and others) report the story that it was named fulminata after this incident. They are clearly mistaken, but it seems that the legion was associated with the battle (and the letter so accepted by Christians lists all the legions supposedly involved but does not mention the twelfth).

Returning to the column, however, there are no lightning strikes accompanying the rain. There are lightning strikes elsewhere (and the Scriptores Historiae Augustae mentions lightning striking enemy siege engines in its life of Marcus Aurelius – but it does not mention any rain). It would seem writers like Dio could not resist the temptation to combine the two moments into one. He was not the only one, however. The contemporary orator, Themistius, reported the contents of a painting he had seen which showed Marcus in the front line of the afflicted Roman troops with his hands raised in prayer. Themistius is the only source to explicitly place Marcus with the troops. Themistius claims that it was Marcus himself who had prayed and whose prayers were answered with the rain shower. The painting also showed his soldiers filling their helmets with rain. The 4th century Christian chronicler Eusebius also wrote of the incident in his Ecclesiastical History and in his Chronicon. He provides us additional details – that Publius Helvius Pertinax was the commander of the Roman forces afflicted by thirst and they were fighting in the land of the Quadi. Eusebius names the enemy as Germans and Sarmatians (as he does in the Ecclesiastical History) but in the land of the Quadi which may imply a coalition of sorts and his detail of Pertinax’s command perhaps contradicts the command of Claudius Pompeianus in the letter (which Eusebius cites and believes) – these two commanders were, however, closely associated with one another in Marcus’ wars. Pertinax would rise to become emperor (briefly) in 193. Eusebius also tells us (erroneously) that the twelfth legion was given the title the Thundering Legion thereafter.

Wikimedia Commons

And yet, the idea of heaven-sent lightning and thunder to win a battle at precisely the right moment was not new. Back in 480 BC, after the invading Persians had defeated the Greeks at Thermopylae, they advanced towards the shrine complex at Delphi, home of the oracle of Apollo (and immense wealth in terms of gifts and dedications). The historian Herodotus recorded that, as the Persians progressed towards the temple of Apollo, ‘just as the Persians came to the shrine of Athena Pronaea, thunderbolts fell on them from the sky, and two pinnacles of rock, torn from Parnassus, came crashing and rumbling amongst them, killing a large number, while at the same time there was a battle-cry from inside the shrine. All these things happening together caused a panic amongst the Persian troops. They fled; and the Delphians, seeing them on the run, came down upon them and attacked them with great slaughter.’ Again, in 279/278 BC, after the Gauls under their chieftain Brennus had defeated the Greeks at Thermopylae, he too advanced on Delphi (his desire to plunder the sanctuaries of the Greeks was one of his explicit reasons for the invasion). According to the geographer Pausanias, the whole area occupied by the Gallic army shook for most of the day accompanied by continuous thunder and lightning. Pausanias tells us that ‘the thunder both terrified the Gauls and prevented them hearing their orders, while the bolts from heaven set on fire not only those whom they struck but also their neighbours, themselves and their armour alike.’

It is into this tradition that the Miracle of the Rain should be placed – the gods (or indeed God) was on the side of Marcus just as at Delphi in 480 and 279 BC. Much later, at the battle of Crécy in 1346, the contemporary chronicler Jean Froissart recorded that a heavy rain, thunder and lightning (along with other portents) took place just before the battle to foretell of the English victory. In the ancient examples, the lightning fell on the enemy telling of their defeat – in later battles too, it foretold defeat – at Adrianople in AD 378 the historian Ammianus Marcellinus described the charge of the Gothic cavalry as like a thunderbolt. Their arrival was followed immediately by the defeat of the Roman forces under the emperor Valens.

Of course, lightning or thunderbolts had long been associated with Zeus and Jupiter and the image was associated with victory in Greek and Roman (and many other) ideologies – coins, sculpture, and statues commemorated victory or foretold it. Greek and Roman sling bullets were designed with such bolts (literally being struck by a thunderbolt – if the sling bullet which hit you had one on it, for instance). But lightning bolts had many other military associations too – in the Jewish tradition, thunderbolts were the arrows of YAWH.

We might even see such an idea all the way through to Blitzkrieg, ‘lightning war’, made do famous by the attacks of Nazi German armies between 1939 and 1941. Theorized by Carl von Clausewitz in the 19th century (but his term was the Schwerpunkt, ‘concentration principle’) but coined in 1935 and put into successful and devastating practice by the armies of Nazi Germany in the first years of World War II. The 20th-century term, however, did not foretell victory, designate divine assistance or even originally mean the swiftness of the attack which can all be seen in ancient examples – it meant a war which should be finished quickly or a ‘strategic surprise attack’. The terror with which we associate Blitzkrieg and which seem so in accord with the ancient examples was not its initial intent of the term even though it does seem to tie into the ferocious, destructive and rapid ideas of attacks by lightning which we can see in ancient accounts.

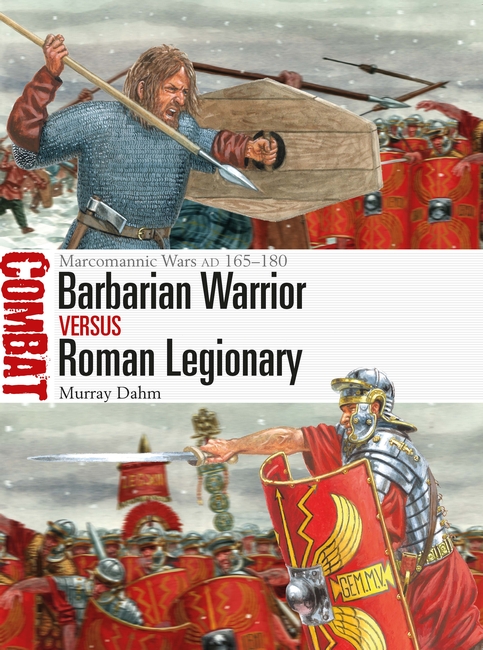

All of these complexities with Marcus’ Miracle of the Rain and his other battles in the Marcomannic and Sarmatian Wars are explored in Combat 76.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment