I’ve been drawn to the battle of Cynoscephalae from an early age. I remember my mother buying me John Warry’s Warfare in the Classical World at a book fair. It kickstarted in me a life-long fascination for and interest in the battles of antiquity. Day in, day out I stared at the battlefield maps and plates that form the beating heart of Warry’s book. And, on page 124, there it was: the battle of Cynoscephalae, presented through a series of battle maps, an order of battle and the briefest of descriptions detailing the movements of the combatants. I was hooked instantly. This first clash between the heirs of Alexander and the sons of Rome gripped me. Pike versus gladius, the involvement of elephants and, above all, the shifting fortunes of the opposing sides, with first Macedon and then Rome having the upper hand in the fighting.

Since those early days, I have retained an avid interest in Hellenistic warfare and Rome’s escalating entanglement in the Eastern Mediterranean. Pursuing these interests further I went on to study Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology and was fortunate enough to be able to travel widely and work across the Eastern Mediterranean on the archaeology of the Hellenistic world, exploring in particular the impact of socio-economic and geo-political developments on material culture. With this book, however, I am realising a life-long ambition to get back to the military history of the period and delve deeper into the battle where for me it all began.

Cynoscephalae is a fascinating battle indeed. It represents the end of the Second Macedonian War and the culmination of three years of active campaigning, during which Rome and its allies repeatedly clashed with the Macedonian soldiers of Antigonid monarch Philip V. It is this long, drawn-out conflict that takes centre stage in Campaign 416. Rather than looking at the battle in isolation, the events leading up to it are covered in detail. In many ways the battle itself, although fascinating in its own right, represents just a small part of a much larger story, involving not only Rome and Macedon but also Pergamon, Rhodes, Aetolia and numerous other Hellenistic polities. Carthage and the Seleucid Empire equally have a part to play in the narrative.

The focus of the book is very much on Philip V, king of the Macedonians and proud descendant of Alexander the Great’s general Antigonus Monophthalmos. Having risen to the throne of Macedon in his late teens, Philip was almost straight away thrust into a war with Aetolia. From here on out, until his defeat on the grassy hills of Cynoscephalae, the king lurched from one conflict to another, fighting campaigns by land and sea. Philip’s motivations for doing so have been debated (from wanting to follow in the footsteps of Alexander or Pyrrhus to pursuing traditional Macedonian security policies), but what seems certain is that the king did not fully appreciate the emerging power and danger that was the Roman Republic. His opportunistic endeavours, which included allying himself with Carthage when Hannibal looked likely to triumph over Rome, were in retrospect ill advised, as were his activities in the Eastern Mediterranean where Philip, in collaboration with the Seleucid king, aimed to take advantage of the weakness of Ptolemaic Egypt. His actions, however, were fully compatible with and expected of that of a Hellenistic king. The shadows of Philip II and Alexander the Great loomed large and, as king of the Macedonians, Philip V was expected to seek glory on the battlefield and expand his domains.

From a Roman perspective the Second Macedonian War represents a key moment in the Republic’s rise to Empire. By severely curtailing the power of Macedon and by removing its traditional hold over mainland Greece, the geopolitics of the Eastern Mediterranean were fundamentally reshaped. Rome was now the dominant force and main power broker in the Mediterranean world, both West and East. Cynoscephalae and the fighting leading up to the final battle also served to highlight the emerging dominance of the armies of the Roman Republic, whose soldiers had recently beaten the armies of Hannibal’s Carthage and now decisively defeated Antigonid Macedon. Philip’s defeat proved a portent of things to come. Soon after the Seleucid Empire also succumbed on the field of battle, relinquishing its control over Asia Minor North and west of the Taurus Mountains.

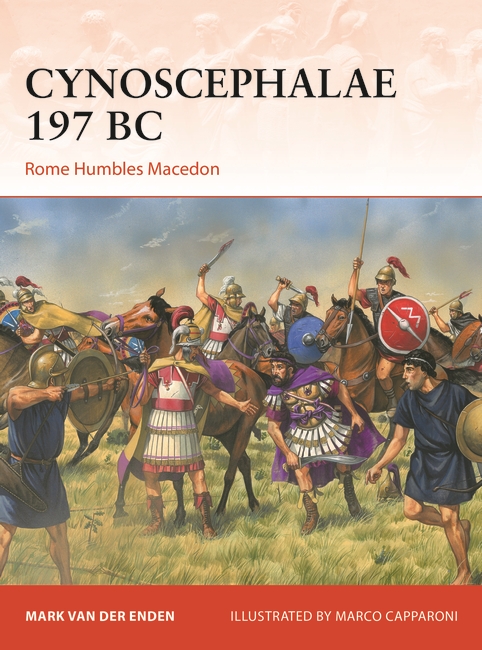

This study sees all the events of the Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC) covered in detail and brought to life by the amazing art of Marco Capparoni. Our narrative account follows the energetic Philip V as the king campaigns across the Balkan peninsula in a determinate attempt to resist the power of Rome. This study hopes to show that the combatants contesting the mountainous country of Illyria and the plains and hills of Thessaly were for the most part fairly evenly matched. Victory hung in the balance and was dependent not only on the merits and deficiencies of the two contrasting military systems (manipular legion vs pike phalanx), but rather more on the generalship of opposing commanders, logistics and supply, strategic manoeuvring of the armies in the field and the fickle fortunes of war. This is aptly illustrated by the two key clashes of the war, the Battle for the Aous gorge (198 BC) and the final confrontation at Cynoscephalae (197 BC). Victory for Rome ultimately rested on the superior generalship of Flamininus, who through clever and timely manoeuvring undid a Macedonian phalanx that had proved up until that point more than a match for its Roman opponents.

Cynoscephalae 197 BC is available to order here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment