It shocked me recently when I realised that I finished my first book about American fighter operations from Iwo Jima, Osprey Aviation Elite Units 21 – Very Long Range P-51 Mustang Units of the Pacific War, in 2005, some 20 years ago. The research and writing I did for that book remain fresh in my mind, and I was pleased to present to readers the illustrations of 30 Very Long Range (VLR) Mustangs, almost none of which were known at that time. Still, I realised that the book failed to answer a big question regarding VLR operations, namely what about the Japanese fighter defences over Tokyo during the spring and summer of 1945?

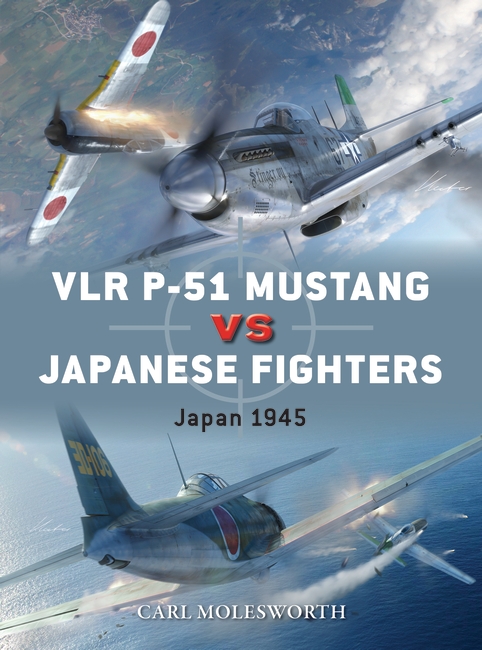

My new book, Osprey Duel 147 – VLR P-51 Mustangs vs Japanese Fighters – Japan 1945 answers that question. I’m sorry it has taken so long to complete the story, and I’m thankful that the structure of Osprey’s Duel series allows me the opportunity to do so. For the purposes of organisation and relevance, I chose to confine the Japanese side of the story to seven fighters – four from the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF) and three from the Imperial Japanese Naval Air Force (IJNAF) – and the organisations that flew them. The IJAAF types are the Nakajima Ki-44 (Allied code name “Tojo”), the Kawasaki Ki-61 (“Tony”), Nakajima Ki-84 (“Frank”) and Kawasaki Ki-100 (no code name assigned). From the IJNAF, I chose the Mitsubishi A6M5/7 (“Zero” or “Zeke”), the Mitsubishi J2M (“Jack”) and the Kawanishi N1K2 (“George”). These were the fighters most often encountered by the Mustang pilots of VII Fighter Command flying from Iwo Jima. Other Japanese fighters saw combat over the home islands in 1945 as well, but they were either twin-engined machines such as the Ki-45 “Nick” and Ki-46 “Dinah” or obsolete fighters in service as trainers (A6M2-K, Ki-27 “Nate” and Ki-43 ”Oscar”) that did not come close to matching the American P-51Ds in performance or firepower. These get only passing mention in the book.

When pilots of VII Fighter Command flew their first mission over Japan on 7 April 1945, neither they nor the Japanese pilots they encountered could guess the campaign that opened that day would last just 13 weeks. Lacking knowledge of the nuclear weapons that soon would level Hiroshima and Nagasaki, all assumed the war would drag on through a bloody invasion of Japan that would not even begin until the autumn of 1945. Instead, the fighting would come to an abrupt end in mid-August. As a result, the P-51 pilots on Iwo Jima flew just 51 missions (4,172 sorties) over Japan during their VLR campaign of 1945, encountering enemy aircraft on 33 occasions.

It is impossible to reduce the results of the VLR campaign to merely a comparison of numbers of successes and losses due to the paucity of statistics available from the Japanese side. Not only were most Japanese records destroyed at the end of the war, but also the Japanese and Americans differed in their systems for assessing their respective combat effectiveness. Thus, while we have documentation for VII Fighter Command claims of 227 confirmed victories, 35 probable victories and a further 100 aircraft damaged in aerial combat, plus another 700 aircraft destroyed on the ground, no such numbers are available for the Japanese forces involved in the campaign. Nor can we assess the accuracy of American claims without Japanese records of their losses. But USAAF records show 214 P-51s lost to all causes (including air-to-air combat, anti-aircraft fire, accidents, weather and mechanical failures). Fewer than half of these resulted in losses of American pilots. Some 86 American pilots were killed, including five of the 14 who became prisoners of war. Among those killed were the 24 pilots who went down in the deadly typhoon of 1 June 1945 before reaching Japan.

The other challenge I encountered in producing this book was the shortage of personal accounts by Japanese personnel who took part in the campaign. While I was able to make personal contact with more than 100 veterans of VII Fighter Command who gave me stories, documents and photographs for my previous VLR book, it was impossible to compile a similar collection of primary material from the Japanese side. The reticence of Japanese veterans of World War 2 to tell their stories has confounded historians ever since the conflict ended, leaving us with just a handful of personal accounts, and those have been retold in books repeatedly over the years. The same is true of photographs showing Japanese aircraft, personnel and airfields during the defence of the Home Islands. Readers will recognise some of the photos in my new book, but I hope that the captions will bring new perspectives to all of them.

You can read more in VLR P-51 Mustang vs Japanese Fighters: Japan 1945

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment