In today's blog post, Bouko de Groot talks about his most recent title, publishing 19th September 2019: Campaign 334: Nieuwpoort 1600: The first modern battle.

The angle

I wanted to write about the Nieuwpoort campaign of 1600, because of its great historical importance, because of the challenge it posed to both armies, and because in recent histories it's been largely overshadowed by far less significant, important and bloody campaigns.

The protagonists

Nieuwpoort was a turning point in the long 80 Years' War between the Netherlands and Spain, or to be more precise, between the parliamentarian-ruled Republic of the United Netherlands, aka the United Provinces, aka – back then – the United States, and the authoritarian-ruled Royal Netherlands, aka the Spanish Netherlands. The campaign pitted both country's young military and political leader against each other: Republican Maurice Count of Nassau, later Prince of Orange, versus Royalist Albert Duke of Burgundy, later Archduke of Austria. They both fought with their backs against the wall, neither would be able to retreat: Maurice had a river behind him and an enemy town, Albert marshes and an enemy fort.

Maurice was far more experienced and the architect of the military revolution that would transform the west. The battle of Nieuwpoort was the litmus test of his reforms. Maurice never lost a battle and was a master of manoeuvre warfare. But during this campaign, Albert surprised him. Albert had little experience, was overconfident, and wasted the one opportunity fate gave him to defeat Maurice. By uncharacteristically sacrificing a brigade (and almost his cousin), Maurice bought his army the time to prepare and ultimately win.

The significance

The campaign and especially the battle of Nieuwpoort was in many ways a turning point of history: it introduced Maurice's military revolution to the world and thereby changed the way of war forever, it pushed the rise of the Netherlands as a superpower and the decline of Spain. Thanks to Maurice and Nieuwpoort, the art of war became the science of war. His revolution – introducing drill, two-part commands and standardization – proved to be the bedrock of later Western hegemony and therefore the world we now live in.

The commands, names and formations he devised and then used at Nieuwpoort we still use today. That's why I've called it ‘the first modern battle’. At first sight the whole campaign seemed to have little operational or strategical importance: none of the goals were reached. However, for the remaining 48 years of the long war the Royalists never dared to fight an open battle against the Dutch anymore. Thanks to their victory, Dutch international political influence grew enormously. The victory was also the beginning of the spread of the military reforms and of the rise of the young, upstart Republic.

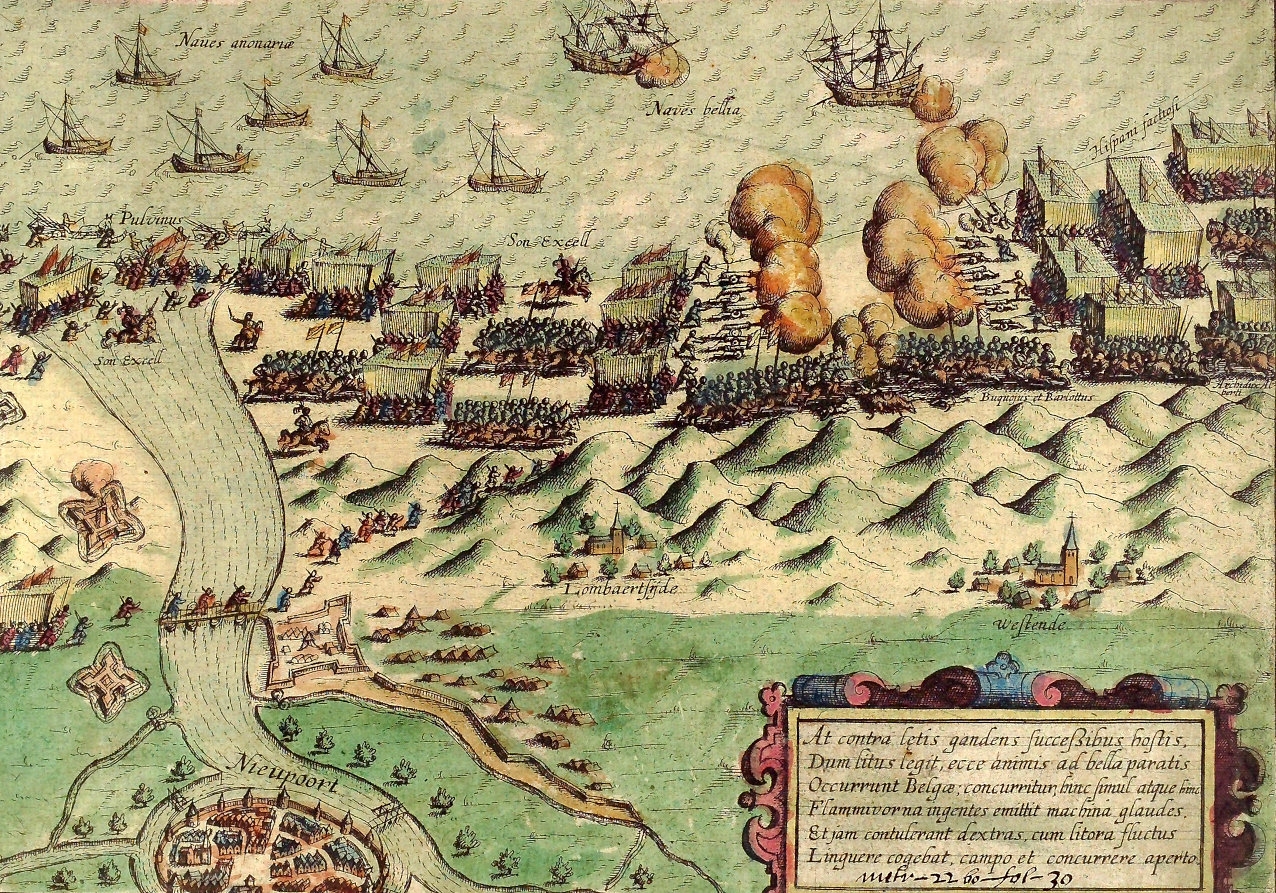

A period illustration of the battle – Anonymous, circa 1600

Courtesy of Atlas van Stolk

The slaughter

Just prior to the main battle, Spanish troops of the Royalist army had murdered and executed hundreds of Republicans soldiers who'd either surrendered under a safeguard or were already unarmed prisoners of war. This atrocity wasn't forgotten when just a few hours later the Royalist army had collapsed and the infantry was surrounded.

At the time it was common for infantry to accept the surrender of enemy infantry once the battle was over. But at Nieuwpoort no mercy was shown to the surrounded Spanish foot. Entire regiments were killed to the last man and ceased to exist. Perhaps half the Royalist foot had by that time dispersed to try to find a way back among the dunes. Maurice however organized a proper pursuit as soon as victory was his. In the hours after their army's collapse, most Royalist routers were cut down by cuirassiers, shot dead by musketeers and calivermen, or drowned when trying to escape through the surrounding marshes.

The bloodshed was unprecedented: the battle of Nieuwpoort, fought between two 10,000-men armies along a front of just 1,000 yards, witnessed a staggering 10,000 men killed, not counting the wounded and prisoners. The entire Royalist infantry was destroyed, mostly killed, and more than 120 banners were captured.

The comparison

The number of Royalists killed at Nieuwpoort was higher than at Rocroi in 1643. That battle was also part of the 80 Years’ War: it was one of the actions by the French in their alliance with the Dutch Republic. The number of Royalists killed was also higher than at Breitenfeld against the Swedes in 1631. That battle was part of the Thirty Years War, in which both the Royalist and Republican Netherlands participated. Yet at Rocroi the Royalist army was more than twice as big and at Breitenfeld more than three times.

The battle of Nieuwpoort was similar in size to Naseby, the decisive 1645 battle of the English Civil War, but far bloodier. There too a Royalist army faced off to a new model Parliamentarian army and lost. The French at Rocroi, the Swedes at Breitenfeld and the Parliamentarians at Naseby, they all used the organizations, drills and formations designed by Maurice and introduced to the world at Nieuwpoort.

A period illustration of the Republicans fording the river – Anonymous, 1730, after Berckenrode, 1600

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

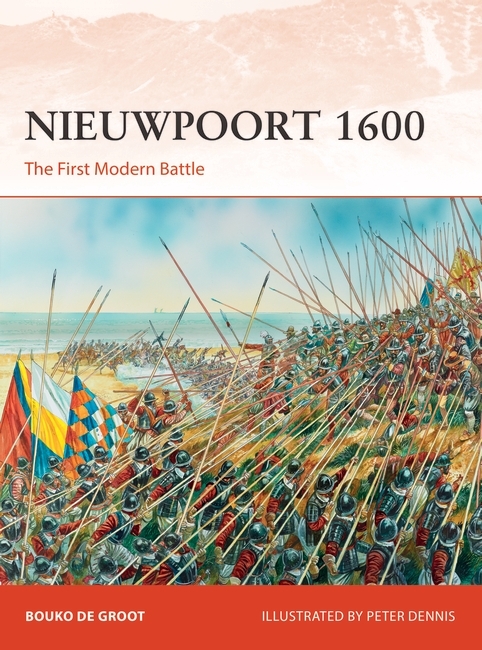

The book

Apart from the 50 or so period illustrations, the book offers a huge amount of specially created content: you'll find six formation diagrams, six detailed maps, three bird's eye viewpoints, three never before published flags by Mats Elzinga, three crowded actions scenes crafted by Peter Dennis, and a gunnery table.

I've described the background of both nations, their armies and the campaign. It contains a comprehensive chronology and a very detailed order of battle for both armies, down to the captain of each company. The text contains one landing, two battles, two sieges, two massacres, ten engagements, and four naval actions. I've also used several pages to explain the average army of the time, so it's clearer how and why the Republicans and Royalists were different.

The details

It wasn't easy to cram so much information onto the limited number of pages of the series format and at the same time tell an entertaining story. So I had to leave out some details. Important topics that didn't fit the flow of the story I've put in captions or diagrams: the special mode of Italian-Spanish skirmish fire, the Dutch advancing fire drill, an explanation of why Maurice chose to use ten ranks, and why the caliver (a shorter, lighter firearm, like a carbine) was still used alongside the more powerful musket.

Other less relevant but nonetheless interesting details I've managed to give a place anyway. Like the logistical needs of an army, the French captain who died from drinking sea water, the German captain who was left for dead but miraculously survived, and the Spanish colonel who died from his wounds, but not after discussing the battle with Maurice.

I also couldn't resist a nod to other important battles. There was a prolonged fight for a little round top, exactly as happened at Gettysburg. The Royalist army collapsed around 1815hrs, the year of Waterloo. Both these battles also saw vicious fighting for a strong position, which too happened at Nieuwpoort at the stronghold. And there is the distinct possibility that Maurice had designed his battle plan on Cannae.

The spoils of war -- Gheyn, 1603

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

The writing

When I set out to write this title, I thought it would be a straight forward English abstract of available Dutch, French and Spanish studies. But like my other titles, I quickly discovered that those studies fell far short of a proper analysis of the actual topic. Most only took a single period source and extrapolated from that, ignoring other sources they might have read wherever those contradict their preferred version. Doing so, they missed most of what makes this campaign and battle so interesting and so important.

That meant I had no choice but to dive into the Dutch, English, French, German, Italian, Latin and Spanish sources myself. That in turn made the whole process much, much longer (hence my heartfelt thanks to my spouse). The order of battle alone for example – only two pages! – took at least a month, just to find the names of those hundreds of captains: in those days there weren't any spelling conventions, so the same name could have a dozen spellings, depending on language, writer and publication.

The insights

So what were the things those other studies missed? Just to name a few important ones: it was the first battle where battalions were used as we came to know them, the first where they were named as such and used in several lines. The battle showed the great effect of drill, the military revolution Maurice had started in the mid 1590s. For example, Republican cavalry could face about as a unit and charge the enemy horse they'd just threaded (charged through) again, in the rear. That and the short rallying time the drilled cavalry needed, meant that Royalist cavalry was completely outclassed. The fact that both armies had to adapt to the terrain and split up into small semi-independent units has been mentioned by many, but not how it was done and what this meant.

Certain losses that seemed out of place now make sense, like the mauling of the left hand battalion of Republican regiment Stad & Land. My reconstruction also shows very clearly that the Royalist foot couldn't cope with the second Republican line replacing the first, in other words, how important that innovation by Maurice was. Modern studies name the battle where Maurice sacrificed a brigade to buy time 'Leffingerdijk', when it actually was at Mariakerke. This title is the first to correctly name that battle and give all the proper details. At the end, in the Analysis, I've also explained what lessons both commanders had learned.

The kind of illustration I didn't use: later reconstructions of the battle. They’re lively but historically inaccurate, although the cuirassier correctly wields his sword in the charge. – Veen circa 1855

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

The next title

The very long war has many other great campaigns. Compared to Nieuwpoort, there were bigger naval operations (Breda, 1637), bigger sea battles (Itacamara, 1640), more daring invasions (Luanda, 1641), more important sieges (Batavia, 1618), and more complex and successful campaigns (Den Bosch, 1629). Of course the war had already been raging for 20 years when Maurice took command, and those years saw plenty of action too: the long sieges of Haarlem (1572) and Leiden (1573) come to mind, both with many land and sea battles (and even one sea battle on land!).

After Nieuwpoort there weren't many more big battles though: because of their bloody defeat in the dunes, Royalist armies avoided regular battles against the Republic from then on. Plenty were offered by Maurice and his successors, but all were refused. The majority of the big battles after Nieuwpoort were meeting engagements (Mühlheim, 1605), assaults (Ammi, 1632), and battles abroad as part of a coalition or by private armies (Worms, 1620; Porto Calvo, 1637).

So, which 80YW campaign should I tackle next?

I've also done these three titles on the 80 Years' War: Dutch Armies of the 80 Years' War, Parts 1 and 2 (Men-at-Arms 510 and 513) and Dutch Navies of the 80 Years' War (New Vanguard 263). Together they list the more than 500 major land and sea battles, sieges and landings of the war. Check out www.80yw.org and the accompanying Facebook group, where I post addenda, errata, many flags researched by me and drawn by Mats, and lots of anecdotes, also from other members.

Nieuwpoort 1600 publishes 19th September 2019. Preorder your copy now.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment