On the blog today, Adlard Coles author Paul E Eden shares a few moments that stood out to him during the writing of his latest book, The Official Illustrated History of the RAF Search and Rescue.

In 2011, I compiled my first ever Royal Air Force Official Annual Review. It’s a title that has meant a great deal to me as a freelance writer and editor – my ninth yearly edition was published early in 2020.

Review introduced me to the extreme professionalism so typical of the RAF and allowed me a choice of operations through which to illustrate it. Knowing that the RAF Search and Rescue Force was scheduled for disbandment, in 2012 I decided to showcase the skill and professionalism of the RAF’s SAR Sea King crews, via a couple of missions from the previous 12 months.

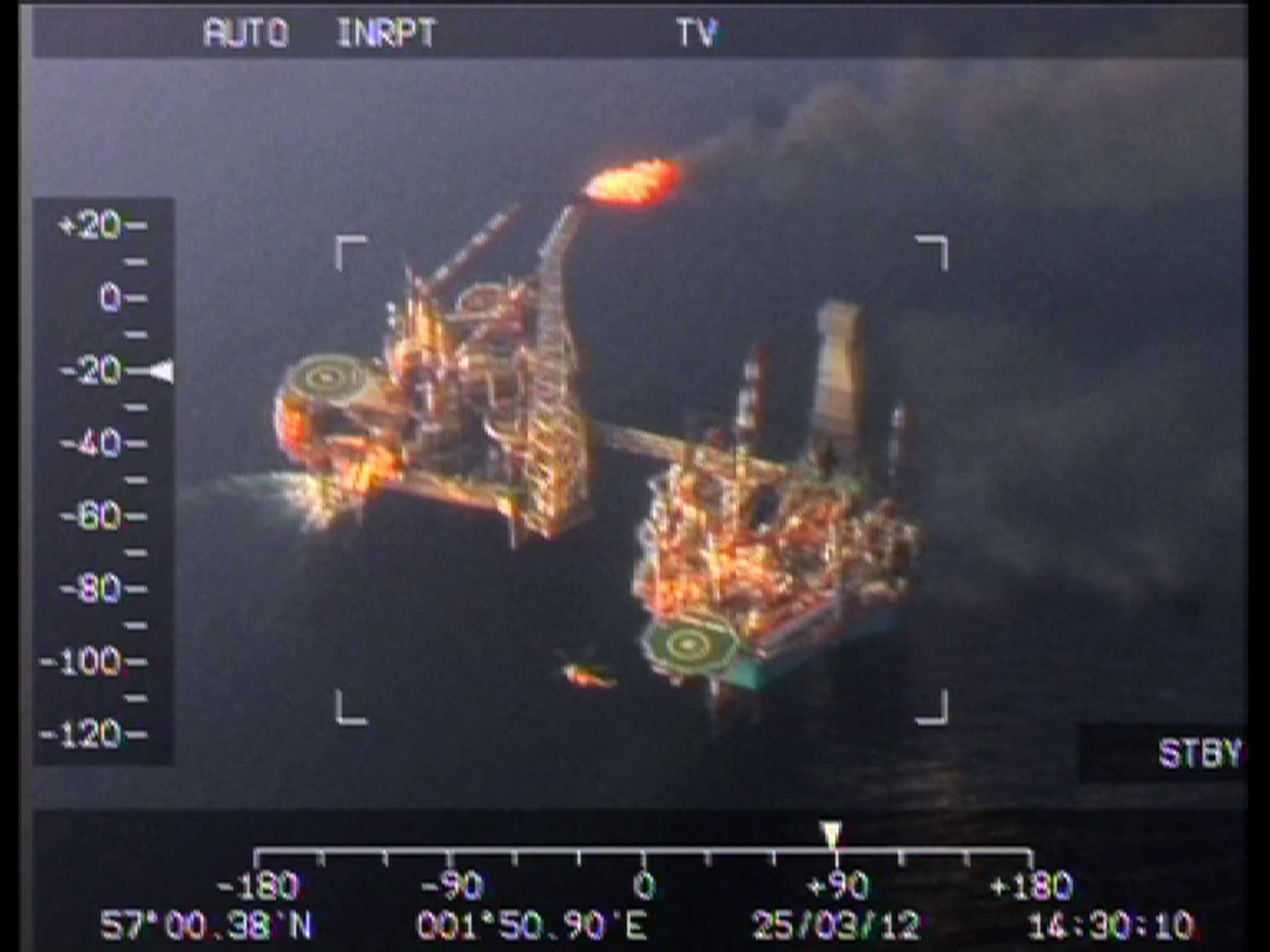

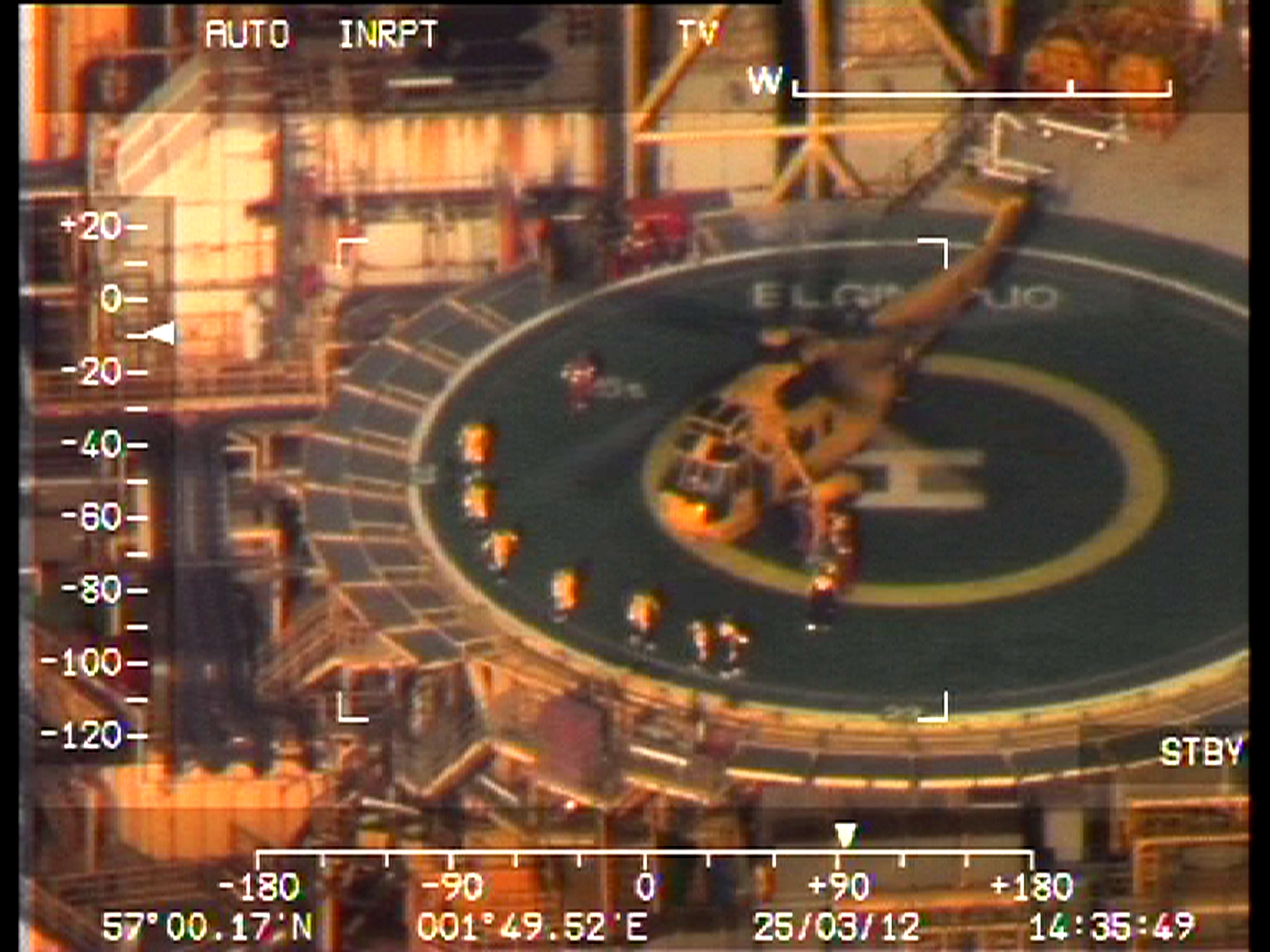

I chose the 25 March 2012 event when a Sea King crew from 202 Sqn’s ‘A’ Flight, operating out of RAF Boulmer, Northumberland, launched in response to a gas leak and fire on the Elgin Well head platform, and the Swanland rescue of 26/27 November 2011. The profound experience of researching and writing the story remained with me and when it was suggested soon after that I might tackle an official, illustrated history of RAF SAR, there was never any doubt that I’d do it.

The Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre, at RAF Kinloss coordinated all UK aerial SAR assets. This photograph was taken 13 months before the Elgin incident_SAC Ben Lees

© UK MoD Crown Copyright

In the Elgin operation, the Sea King took a particularly unusual role, standing off to act as rescue coordinator. With seven helicopters engaged, among them another RAF Sea King and a Norwegian SAR aircraft, Flight Lieutenants Iain Cuthbertson and Gareth Dore, and Flight Sergeants Nigel Mortimer and Andrew Rowland managed the situation with skill and calm professionalism.

The Elgin (on the left) and conjoined Rowan Viking platforms, seen from RESCUE 131’s electro-optical turret

© UK MoD Crown Copyright

The November 2011 incident was quite different. The cargo ship MV Swanland was swamped in heavy seas west of Lleyn Peninsula in the Irish Sea. Laden with 3,000 tons of building stone, the vessel broke up and sank, leaving its crew little time to abandon ship. A Sea King HAR3 from ‘C’ Flight, 22 Sqn, RAF Valley, was the first helicopter on scene, effecting a rescue that was dramatic, dangerous and tragic in turn.

The mission could have been flown by any RAF crew on any rough night. This abridged extract from The Official Illustrated History of RAF Search and Rescue ought to be considered with that in mind.

Flight Lieutenant Thomas ‘Sticky’ Bunn was on shift the night of the Swanland mission. “I was the 22 Sqn, ‘C’ Flt Op Captain that night. Flight Lieutenant William Wales was my co-pilot, Sergeant Graeme ‘Livvy’ Livingston my RadOp [radar operator] and MACr [Master Aircrewman] Richard ‘Rich T’ Taylor was winchman. The wind was already howling when we went to bed and I half expected the ‘job phone’ to ring that night, but hoped it wouldn’t.

Flight Lieutenant Thomas ‘Sticky’ Bunn was captain on 22 Squadron’s initial response to the Swanland incident_SAC Faye Storer

© UK MoD Crown Copyright

“The phone woke William at 02:20hrs and we learnt it was an overwater ‘wet job’ which, from a flying point of view, was preferable to going to the mountains in 40kt of wind and rain at night. We quickly became aware that this was a serious job, with the coastguard reporting a ship breaking up 30 miles southwest of RAF Valley. As a crew we knew this wasn’t an everyday job and as I got into my immersion suit the adrenaline was flowing.”

Wales takes up the story: “The call came into my bedroom at Valley – the co-pilot’s bedroom had the phone next to the bed; it always woke me with a jump! Collecting all the information I needed and waking the others, I could already hear the wind and rain outside. Then I walked into the ops room and heard Holyhead coastguard blaring out a mayday call to all vessels and realised this was a little bigger than I’d first thought.”

Wales described the rescue scene as chaotic as the crew set about checking debris and liferafts. Having seen sailors safe in one dinghy, attention turned to looking for survivors in the water. Then: “We found another liferaft… and put the winchman down, in fierce conditions, to check inside, but there was no one in it. Then the liferaft rolled, with Rich T inside.”

“We elected to put me down,” Taylor recalls. “It was quite challenging. The pilots ended up having to fly manually. After several attempts at getting me inside, I ended up in the water alongside it, then a big wave lifted me up and carried me into the dinghy. It was pitch black inside because the aircraft had moved away quite a bit. I began searching the raft. And that’s when it rolled over.

“I was under the water for some time and the pilots and winch operator were quite concerned. If they’d just winched in, they could have dragged me through something and injured me, so they had to let the situation develop. Luckily, I popped up, in a bit of a spluttering mess, but on the wrong side of the dinghy. I had to swim underneath to get back to the aircraft side. They recovered me and I was pretty pooped; it was really swim for your life stuff.”

Sticky recalls: “Livvy reported Rich T swinging towards and entering the water, and then the dingy flipping. This wasn’t pretty and I feared for him. At some point he came out of the dinghy and we recovered him back to the aircraft. Our hearts sank when Rich told us the dinghy was empty.”

From his seat beside Sticky, Flt Lt Wales had an intimate view of his captain in action. “He remained calm and in control throughout. He had to fly the rescue manually, a tricky procedure for non-SAR crews; normally we would use the RadOp in the back, with a joystick to steer the hovering aircraft over the liferaft. However, in this case the kit wasn’t working because the waves were so big, and Sticky had to fly it with minimal visual cues, because it was so dark and there were walls of water coming at him.”

With Rich T safely back in the cabin, the crew was determined to find the first dinghy. On the way, the helicopter flew over a large debris field and an emergency beacon broke through on the radios. “We became hopeful this was where we would find survivors and started to search methodically upwind. We saw survival aids, floats, doors and lots of debris ripped from the ship, but no survivors,” Sticky remembers. “This was when it hit home that a ship really had gone down. Right there.”

And so I was inspired and enthralled in equal measure, but could boast no more meaningful insight into RAF SAR than these two operations had given me. I had in mind a story about yellow helicopters plucking those in peril from snowy mountain tops and rough seas. I knew something about the Sea King and its Wessex and Whirlwind forebears, and thought I was good to go.

With conditions suitable for landing, the Lossie Sea King also set down for speedier boarding. Rig workers follow strict procedures for safe helicopter operations

© UK MoD Crown Copyright

But very soon I learned that the RAF hadn’t started painting its rescue helicopters yellow until 1957, a good five years after it began developing SAR techniques with the Westland Dragonfly and Bristol Sycamore. And then I realised the significance of helicopter rescue could only be made clear through an understanding of what had come before.

That meant describing the combination of air-sea rescue launches and fixed-wing aircraft the RAF had relied upon since early 1941, and the shocking realisation, therefore, that there had been no formal air-sea rescue organisation during the Battle of Britain. Reasoning that a good number of readers might be surprised to learn of the RAF’s expertise with ocean-going boats, I felt the need to explain how the service became an expert operator of a large fleet of various craft, which meant taking the story back to the RAF’s formation on 1 April 1918.

I started out to write little more than the eight-year history of RAF SAR Force, but ended up writing an account of RAF air-sea rescue and SAR covering the Service’s first 102 years. The tale has surprised me at every turn and I hope readers will enjoy discovering the people, aircraft, boats and stories of calm professionalism in the face of imminent danger as much as I have.

The Official Illustrated History of RAF Search and Rescue is out now. Get it direct from our website (with a 10% discount) here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment