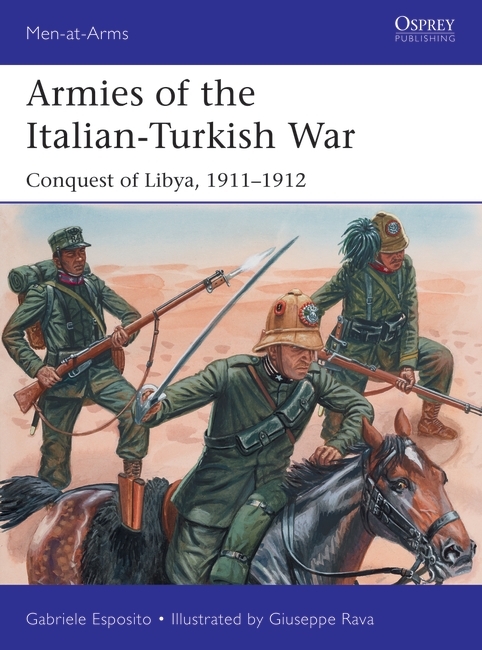

Gabriele Esposito's newest Men-at-Arms title, Armies of the Italian-Turkish War, chronicles and illustrates Italy's conquest of Libya during the Italian-Turkish War, which involved not only the armies and navies of both sides, but also a number of tribal insurgents. In today's blog post, Gabriel recounts the build-up to this conflict.

The Italo-Turkish War, which lasted thirteen months between 1911 and 1912, is one of the lesser- studied conflicts in military history of the early 20th century. This may be because it was a war that was quite difficult to define: it had all the main characteristics of a colonial war as it was fought in Africa by an European power that wanted to acquire a new colony, but it was also fought outside Africa in some key areas of the Mediterranean Sea.

The two countries that fought each other were very different and were experiencing different historical change: The Kingdom of Italy had completed the difficult process of national unification in 1870 with the annexation of Rome, and thanks to the large population of this new country and their nationalistic ambitions, the Italians had started to act as a major European power with regard to their foreign policy. Similar to recently-unified Germany, Italy wanted to develop a colonial empire outside of Europe, however, she knew she had to act quickly in order to conquer the last remaining African territories that were still free from any form of colonial rule. The ‘scramble for Africa’ had already started and the richest regions of the Black Continent had already been occupied by other European countries. Italy had already experienced a series of political run-ins with France, since both countries had common colonial objectives – the most important of these being Tunisia, a country located very near the Italian peninsula but with a massive border with French Algeria. The Italian government did its best to impose a form of protectorate over Tunisia but, in the end, Tunisia was absorbed into the French sphere of influence in 1881. This was a huge international humiliation for Italy since it appeared that other major powers could just take and conquer any territories they wanted.

With no more hopes of expansion within North Africa, at least for the moment, the Italians turned their attention to the Horn of Africa: this area of the Black Continent was the only one that was still mostly free from colonialism. In 1882, the Italian government bought the port city of Massaua on the coast of Eritrea from a private company and started to colonize the region. At that time, Eritrea was governed by a series of local aristocrats who were formally subjects of the Ethiopian Empire and enjoyed a good relationship with the Ottoman Empire (the Turks controlled the Arabian coast located in front of Eritrea). The Ethiopian Empire, known as ‘Abissinia’ by the Italians, was the major power of Eastern Africa and its strong military resources had prevented the colonization of its area. Initially, the Italians were able to avoid conflict with the Ethiopians and cemented their occupation of Eritrea which became the first Italian colony in 1890. At the same time, however, Great Britain and France had also turned their attentions to the Horn of Africa and in particular to the coastal regions. Moving south of Eritrea in 1882, the French established a protectorate over the strategic city of Gibuti and, in 1884, the British did the same over the coastal territory located in front of Aden (which became known as ‘British Somaliland’). The Italians were taken back by these moves from their rivals and, in 1889, decided to create their own protectorate over a large portion of Somalia that was still free from foreign rule. In 1908, the Italian colony of Somalia was formally established.

At the same time, the Italian government started to plan further expansion into the heart of the Ethiopian Empire. The occupation of Eritrea had been quite simple to achieve and the Italians hoped that the conquest of Ethiopia would also be easy thanks to their military superiority. In 1895, the Kingdom of Italy invaded the Ethiopian Empire from Eritrea. On 1 March 1896, at the Battle of Adwa, the Italian invading force was completely crushed by the Ethiopian Army. Nearly 11,000 Italian soldiers were killed, wounded or captured – it was a complete disaster for Italian colonialism and another enormous, international humiliation for the young kingdom. From a military point of view, it was the worst defeat ever suffered by a European army during the colonial wars: a large force equipped with modern firearms had been defeated by an army that was still mostly tribal in nature.

After 1896, Italy had to abandon all their plans related to the conquest of Ethiopia and start to focus on other areas of the African continent. They would eventually return to Ethiopia in 1935, on the orders of Mussolini, to revenge the deaths of Adwa.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Ottoman Empire was a multinational country in decline. Humiliated in the Crimean War, the Turks had been obliged to renounce most of their Balkan territories during the second half of the 19th century. Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, Romania and Bulgaria had all became independent from Ottoman rule and, as a result, the Turkish presence in Europe had been reduced to a few territories who had little or no political importance (Albania, Macedonia and Thrace). The new Balkan states were particularly aggressive in their foreign policy against the Ottoman Empire and took advantage of the fact that it was on the brink of collapse: the Turkish economy was in an extremely bad state, the army was not strong enough to protect all of its vast territories, Asian minorities were on the verge of revolt, many social problems were still unresolved and the whole country was torn apart by a violent internal struggle between conservatives and reformists. In 1912, during the last month of the Italo-Turkish War, the expansionism of the new Balkan states would lead to the outbreak of the first so-called ‘Balkan War’ that re-drew the political map of South-Eastern Europe with the newly-found independence of Albania and other countries.

The Ottoman Empire, however, did not just comprise of Turkey and some Balkan territories; at the beginning of the 20th century, it still controlled large areas of the Middle East (Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, Arabia) and the territory of Libya in North Africa. The latter was the last remnant of the once-glorious Turkish presence in that part of the world. At the beginning of the 16th century, the Turks had conquered most of North Africa and turned the Mamelukes of Egypt into their vassals, conquered Libya and established a protectorate over the territories of Algeria and Tunisia. Only Morocco, in the extreme west, remained independent. Since the beginning, the North African provinces of the Ottoman Empire enjoyed widespread political autonomy: Egypt became a semi-autonomous state after the French invasion led by Napoleon; Algeria and Tunisia, however, became main bases for Barbary Pirates and were known as ‘pirate states’ that launched naval incursions into the Mediterranean.

During the 19th century, European incursions into North Africa were apparent: Algeria was invaded by the French in 1830 and, in the same year, Tunisia became virtually independent from the Ottoman Empire. Later, during 1881-1882, the French imposed their protectorate over Tunisia and the British did the same with Egypt. Of the former Ottoman territories in North Africa, only Libya remained inside the Turkish sphere of influence. Libya had also been a base for the Barbary Pirates during previous centuries, but their presence had never been as strong as it was in Algeria or Tunisia. Libya had also never had a strongly autonomous local government like other Ottoman territories in North Africa and, as a result, in 1910, Libya was still firmly part of the Ottoman Empire and had a Turkish military garrison. The country was, though, quite isolated from the rest of the Empire and could only be reached by sea – the Turks did not have an efficient fleet and it was difficult to send supplies from Asia. It was also mostly covered by desert and seemed to have no natural resources at all (they were only discovered some decades later); the population was scarce and divided into hundreds of tribes, most of whom were nomadic and all of them at war against each other; there were no infrastructures to speak of and the economy was in a bad state. Libya had also, historically, been divided into two different areas with populations who had quite different lifestyles and traditions: Tripolitania in the east with Tripoli as its capital and Cirenaica in the west with Bengasi as its capital. The few significant cities of the country were located on the Mediterranean coast and south of Tripolitania and Cirenaica, was the Sahara Desert with the inhospitable but immense region of Fezzan.

On the surface, Libya did not have anything to offer to a European colonial power, but at the beginning of the 20th century, it became the main target for Italy’s expansionist policy.

With the opening of the Suez Channel in 1869, the Mediterranean had regained most of its previous strategic and commercial importance. As a result, control of the central portion of the ‘Mare Nostrum’ became fundamental for all those countries who had important colonies in Asia (like British India or French Indo-China). Italy, a long peninsula extending for hundreds of miles in the central Mediterranean, occupied a key location with regard to the Mediterranean. By conquering Libya, which was located exactly south of Sicily, the Italians could transform the central Mediterranean into a sort of ‘Italian lake’ and gain power and prestige by doing so. They were desperate to show the world that their country too was a great power and could conquer and colonize like any other. A war with an ex-power in complete decline like the Ottoman Empire seemed to be the perfect solution.

In addition, colonial expansionism would be a solution for their many internal problems. After Unification, the population had expanded exponentially, but the national economy had not been able to sustain this expansion –there was not enough work, and food was scarce especially in the poor and rural areas of the south. As a result, thousands and thousands of Italians were forced to emigrate to the United States and South America during 1870-1910 to survive and earn a living. The Italian government hoped that the conquest of a colony located near the Italian mainland would help resolve this problem. New emigrants could settle in Libya as peasants and farmers, transforming a desert country into a fertile one and ensuring it remained Italian territory while contributing to the development of their own country.

At the time Italy was governed by Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti, one of the greatest Italian politicians of all times. He had been keeping the growing social unrest under control by establishing good relationships with representatives of the Italian workers’ class and the outbreak of a new ‘small’ war would be positive for expanding Italian industry and for workers who would be needed to produce military weapons. When, in 1908, the so-called ‘Young Turks’ Revolution’ took place in Istanbul, the Italians finally decided that the moment had arrived to search for a ‘casus belli’ to attack the Ottoman Empire. (In Turkey, the reformist group of the ‘Young Turks’ (mostly composed of young military officers) took power via a coup and limited the prerogatives of the Sultan by installing a new constitutional monarchy.)

By 1911, Turkey was just starting the long process of progressive modernization which was quite far from being completed. Italy, however, was still searching for an effective excuse to start a war against them. The occasion finally came during the summer of 1911 when the famous ‘Agadir Crisis’ took place. This was caused by the French attempting to create a protectorate over Morocco which was still an independent monarchy (at least on paper). Since Germany wanted to do the same, the two European powers and their respective systems of international alliances came very close to open war. The Germans sent their warship ‘Panther’ to the Moroccan port of Agadir, determined to stop French expansionism in North Africa. The British government strongly supported the French and, in the end, the Germans were obliged to concede. In exchange for acceptance of French rule over Morocco, the German Empire received some territories that previously had belonged to the colony of French Congo. Once again, Italian public opinion was outraged by the ease with which the French had acquired such an important part of Africa. It seemed the time had come to make Libya one of their own colonies. On 19 September 1911, the Italian Army was officially mobilized and an expeditionary corps of 34,000 soldiers was assembled. Nine days later, the Italian ambassador in Istanbul gave an ultimatum to the Ottoman government: Libya had to be ceded to the Kingdom of Italy in 24 hours. The Turks did not respond in time to the ultimatum and on 29 September 1911, the war began.

Armies of the Italian-Turkish War is out today! Get your copy here.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment