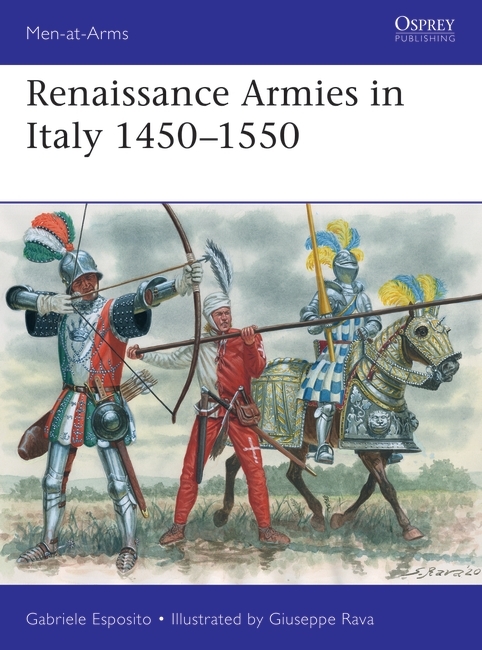

The recently released title, Renaissance Armies in Italy 1450–1550 looks at the organization, equipment, and campaign record of the various armies fighting within Italy during the major wars of the period. On the blog today, author Gabriele Esposito examines the Italian militia involved in the years preceding the battle and the conflicts themselves.

The Italian period commonly known as the ‘Rinascimento’ or the ‘Renaissance’ was the age of great cultural and social improvement which saw the end of the Middle Ages and the feudal system that had been so prominent in most areas of Europe during the previous centuries. With the development of a new way of thinking, which considered human nature as the centre of knowledge, religion lost most of its importance, and curiosity and rational thinking became the dominant ideal leading to the development of new sciences and the flourishing of the arts.

The ‘new man’ of the Renaissance felt a strong need for a culture that could explain the complexity of the age in which he was living, and arts and culture from Greece and Rome quickly became the basis of this new cultural world.

From a historical point of view, 1453 and 1559 are often considered to be the beginning and end of the Renaissance. In 1453, the Hundred Years’ War between England and France ended with the unification of France as a nation, soon to become one of Europe’s most dominant military powers. In the same year, Constantinople and the last remnants of the Byzantine Empire were conquered by the expanding Ottoman Turks. These two events had great consequences for Italy: the first marked the emergence of a potential threat to Italy’s northern borders and the second led to the emigration to Italy of hundreds of Byzantine men of culture from Constantinople.

The arrival of Greek scientists and artists from the Levant brought Italy a great amount of knowledge that had not been destroyed by the Turks and sparked new interest in the ancient civilizations of the Greeks and Romans, of which the Byzantines had been the direct heirs for centuries. Italian culture was deeply affected by these new ideas coming from the east: Byzantine men of culture taught their Italian equivalents how to read and translate ancient Greek languages, whilst all arts were influenced by models from Antiquity.

In 1454, with the signing of the Peace of Lodi, Italy entered into a period of political stability. After decades of internal wars, the Ottoman menace had become apparent and Italians decided to put aside their regional rivalries for peace. For the following 40 years, Italy would enjoy a period of great peace and prosperity that favoured the development of Renaissance ideas and practices. In 1494, however, Charles VIII, King of France decided to invade Italy and this political stability was destroyed. Soon after, other foreign powers joined the fight for possession of the peninsula; which marked the beginning of the long and bloody ‘Italian Wars’, a series of conflicts involving Italian states and other major military powers such as France and Spain. Despite this, 1494-1550 were still important years for the artistic Italian Renaissance with Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raffaello and many others producing great works of art.

In 1559, with the signing of the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, the Italian Wars ended and Spain emerged as the dominant power on the peninsula while the French were forced to renounce most of their expansionist ambitions. The end of the Italian Wars coincided with the end of the Renaissance: development of knowledge slowed down and Italian art lost its prominence in Europe. New changes were taking place in the World. With the discovery of the New World, the Mediterranean Sea became a secondary market for most international trade and Europe turned its attention to the Atlantic. The Italian states lost most of their political autonomy and became only minor participants in the new international order that was emerging. The immense cultural heritage produced by Italy during the Renaissance, however, had changed the world forever and is still considered today as the fundamental basis of our way of being.

The Rise of the Italian State

During the Middle Ages the Italian peninsula had seen the rise of the ‘Comuni’, independent city-states that flourished thanks to commerce, and which were constantly at war against each other. The Comuni had emerged as autonomous political entities from the struggle against the Holy Roman Empire which encompassed the northern and central part of the Italian peninsula. Since the early XIV century, after having suffered many military setbacks in the region, the Holy Roman Emperors decided to abandon all their claims over Italy; and, as a result, the Comuni gradually transformed themselves into real states and entered into a new phase of their history.

In the southern part of the peninsula, the situation was different: the system of the free Comuni had never developed and the whole region was a single state: the Kingdom of Naples, ruled for a long time by foreign royal families and characterized by the presence of a strong feudal nobility (something that did not exist in the rest of Italy). Situated between the Comuni of the north and the great feudal monarchy of the south were the Papal States. Since the early Middle Ages, the Catholic Church had been gradually creating a state in central Italy by assembling cities and provinces. This state had played a prominent role in the struggle against the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages but during the XIV century it lost most of its political importance when the Holy Seat of the Papacy transferred from Rome to Avignon (in southern France). After centuries of autonomy and power, the Pope became a hostage to the King of France. Left without a head of state, the Papal States entered into a period of anarchy: most of the largest cities transformed themselves into free Comuni, whilst the countryside was dominated by feudal lords.

By the beginning of the XV century the political situation in Italy had started to change and the enormous internal fragmentation that had characterised the previous decade was beginning to fade. In northern and central Italy, free Comuni started to disappear and were substituted by larger local states known as ‘Signorie’ - Comuni where a prominent, aristocratic or middle-class family assumed control of the city and started to rule as a dynasty. Initially most of the Signorie retained their original republican form of governing; in practice, however, power was exerted directly by the Signori who did not want to cause internal turmoil by abolishing existing forms of government. Over time, the most important Signorie started to absorb smaller Comuni located around them and, as a result, gradually transformed themselves into regional states with one very important urban centre as a capital.

While this was happening in northern and central Italy, in the south, the Angevin (French) royal family ruling the Kingdom of Naples was deposed by a new Aragonese (Spanish) dynasty. The Aragonese already controlled Sicily (from the end of the XIII century) and now unified two Italian kingdoms under their monarch.

In 1377, the Pope returned to Rome and the Papal States were retaken by the Spanish cardinal, Egidio Albornoz,, leading a mercenary army. He gradually subdued all the Comuni and feudal Signorie within the territory and, by the second half of the XV century, the Papal States were once more unified under the guidance of the Holy Seat.

In 1454, with the signing of the Treaty of Lodi, Italy adopted a new political structure that remained mostly unchanged until the end of the Renaissance. This was based on five main regional states: the Duchy of Milan and the Republic of Venice in northern Italy; the Republic of Florence and the Papal States in central Italy; and the Kingdom of Naples in southern Italy.

The Duchy of Milan had emerged as one of the most important military powers of Italy during the second half of the XIV century after absorbing all the other Signorie of Lombardy under the leadership of the powerful Visconti family. The Visconti established the Duchy in 1395 and continued to rule until 1447. Three years later, after a brief interlude with a republican ruling body, the Sforza family assumed control over Milan and continued the power policy initiated by the Visconti (who had previously contracted the Sforza as their mercenary military commanders).

The Republic of Venice has, perhaps, one of the strangest histories amongst all the Italian states. From a formal point of view, Venice was an oligarchic republic lead by a ‘Doge’ (Duke) who was elected by the most prominent citizens/merchants of the city. It had always enjoyed a greater degree of autonomy from the Holy Roman Empire and, as one of the Comuni, had gradually expanded its territory into the eastern part of northern Italy and also towards the Balkan coast of the Adriatic Sea. By the beginning of the XV century, the Venetians had conquered large parts of Dalmatia in present-day Croatia and were expanding into the Aegean Sea in order to occupy some of the former Byzantine Empire. During the first half of the XV century, Milan and Venice fought for dominance over northern Italy and this long struggle (ending with the Peace of Lodi) gave the western part of northern Italy to Milan and the eastern part to Venice. Naval commerce was the key factor behind the success of the Venetians, who had the most important fleet of Renaissance Italy.

In addition to Milan and Venice, another two regional states had a certain importance in northern Italy: the Republic of Genoa and the Duchy of Savoy. The first was the main rival of Venice in the Mediterranean Sea; during the XV century, however, Genoa was occupied for several brief periods by the Kingdom of France and by the Duchy of Milan (which badly needed an outlet to the sea). The Duchy of Savoy (recognized as such in 1416) in contrast, was a large feudal state located on the western borders of northern Italy. From a cultural point of view, it had much more in common with France than with the rest of Italy and,after the unification of the Kingdom of France in 1453, the Duchy became a vassal state of the French and would only regain its full independence with the peace of Cateau-Cambrésis.

During the Middle Ages, Florence had been the most important of all the Italian Comuni (together with Milan) when in 1415-1420, the city was taken over by the powerful Medici family. The Medici had the most important and flourishing bank in Europe and dominated the economic life of Italy and influenced politics in other foreign nations. The Medici, especially Cosimo the Old, gradually assumed control of the Florentine Republic by being elected to the most prominent positions in the state. The family knew that Florentines were extremely jealous of their republican freedoms so they never abolished the traditional political institutions of Florence but simply ‘occupied’ them in a way where they could use their influence (by sometimes illegal means).

The Papal States controlled a large portion of central Italy and continued to expand during most of the Renaissance; during the latter period various Popes acted as rulers and often fought at the head of their armies in full armour. In contrast to the Signorie, which were ruled by a family or by oligarchic groups, the Papal States had an absolute monarch who was elected by the cardinals. When the Spanish Borgia family tried to change this, by transforming the Church into a dynastic monarchy, most ofItaly turned against them to maintain the status quo. The Papal States wanted to expand towards Tuscany (dominated by Florence) but also towards the southern territories of the Venetian Republic.

The Kingdom of Naples, in southern Italy, had the largest army of the peninsula and was ruled by the Aragonese royal family. They were politically independent from the main dynasty that controlled the Kingdom of Aragon in Spain, but were part (from an economic point of view) of the Aragonese ‘commercial empire’ that comprised several regions of the Mediterranean (like Sardinia). In 1458, after 14 years of unification with the Kingdom of Naples under the same monarch, the Kingdom of Sicily regained its formal independence and returned under the direct rule of the Kingdom of Aragon. As a result, Sicily was not involved in the most important political events of the Renaissance (unlike the Kingdom of Naples, which was one of the main protagonists).

Italian Militia during the Renaissance

During the XIV century, with the transformation of the Comuni into ‘Signorie’, traditional Italian military organization based on urban militias made up of well-trained infantrymen was gradually substituted by a new one that had, as a central element, units of mercenary professional soldiers. The middle classes of the various Italian cities, which had been the core of the Comuni’s infantry were no longer interested in military matters as they had been before: during previous centuries, serving in the urban militias had been the only way to mark their social ascendancy and reduce the power of the feudal aristocracy; now, thanks to their work as artisans and merchants, they had become rich enough to pay someone else to perform their military duties. The wealthy citizens of the ‘borghesia’ had nothing to earn from military service, but a lot to lose: for this reason, citizens/soldiers of the previous period disappeared quite rapidly from the battlefields of Italy.

The new mercenary troops at the service of the various Signorie were organized into ‘Compagnies di ventura’ (Mercenary Companies), which comprised a few hundred soldiers to several thousands of professional fighters. Initially the mercenary soldiers mostly came from outside Italy, but in time, an increasing number of Italians started to choose this as a profession.

Each Company was commanded by a ‘Capitano di ventura’, who was responsible for the recruiting and administration of the mercenaries at his command. The Mercenary Captains signed contracts with the civil authorities of the various Signorie that requested their military services; these contracts, sometimes extremely complex and detailed, were commonly known as ‘Condotte’. As a result, the Capitani di ventura were frequently called ‘Condottieri’ and the Compagnies di ventura could also be known as Condotte.

In most cases these warlords were cadet sons of aristocratic families who had no choice but to serve as military commanders in order to obtain a prominent social position. On many occasions these Condottieri were able to create their own Signorie or to replace the families for which they were fighting (the Sforza did this in Milan with the Visconti family). Quite frequently a Condotta could represent the entire army of a Signoria and, as a result, if a Condottiero abandoned his contractors to change side, the destiny of an entire war or of an entire city could be decided by the will of a single man. The only way to ensure the loyalty of these mercenary commanders was to pay them immense sums of money, with the result that most of the Italian states were nearly always on the verge of bankruptcy during the Renaissance period.

From an organizational point of view, the Compagnia di ventura or Condotta had, as their main tactical unit, the ‘Lancia’ (literally ‘Spear’): this consisted of three men and five horses. The first man, known as ‘Elmetto’(‘Helmet’) was a man-at-arms equipped with the full armour of a heavy knight; the second man, known as ‘Scudiero’ (‘Esquire’), was a lightly-equipped cavalryman; the third man, known as ‘Paggio’ (‘Page’), acted as an infantryman on the battlefield and as a servant during daily life. Of the five horses, two were of good breeding (‘destrieri’) and were employed by the man-at-arms, while the other two were of lesser breeding (‘ronzini’) and were employed by the esquire/light cavalryman; the last horse was used by the page to transport the various equipment of the ‘Lancia’. In addition to the scudieri of the Lancia, some Italian armies of the Renaissance also included some other contingents of light cavalry; usually from outside Italy: the Republic of Venice could count on the excellent ‘Stradiotti’ coming from the Balkans and the Kingdom of Naples, Albanian light horsemen.

The Lancia of other European countries, like France or Burgundy, comprised of two additional specialized infantrymen who could be archers or crossbowmen (arquebusiers during later times). In Italy, the kind of Lancia with five components never became popular because contingents of specialized infantrymen always remained as a distinct military component in various armies.

From 1464, the Papal Army started to deploy a kind of Lancia with five men (one man-at-arms, two scudieri and two paggi) known as ‘Corazza’ or ‘Cuirass’, but this tactical unit remained a local experiment.

Each Italian army of the Renaissance period also comprised a certain number of men-at-arms who served individually with their Lancia and not as part of a Condotta; these professional fighters and their personal retainers were known as ‘Lance spezzate’ (‘Broken spears’) precisely because they were not part of a Condotta but made up an independent Lancia. Often the heavy knights of the Lance spezzate were former members of a Compagnia di ventura that had been dissolved and assembled together under the command of a mercenary warlord to form a new Condotta. Generally speaking, they were much more loyal to their employers than the members of an ordinary Lancia.

The Lancia of each Condotta could be assembled into larger units to perform specific purposes or to fight in a pitched battle: five Lancia made up a ‘Posta’ and five ‘Poste’ made up a ‘Bandiera’; ten Lancia could be assembled to form an ‘Insegna’, while from twenty to thirty Lancia could be assembled to form a ‘Squadra’. The latter kind of unit, equivalent to a later squadron, was the largest military corps into which a Condotta. could be divided. Each Squadra was commanded by a ‘Squadriere’, who was a minor ‘Condottiero’ serving at the orders of a more important warlord.

The contracts signed between the ‘Condottieri’ and their employers (who could also be private citizens) contained a series of clauses related to length of service, pay, number of troops and type of troops; they also sometimes contained points dealing with provisions, tax and toll exemptions for the mercenaries, discipline and inspections, punishments in case of desertion or betrayal and much more.

The period of service for a Condotta initially lasted only three or six months; later it was increased to 12 months, divided into two phases: the first six months of ‘ferma’ and the second six months ‘di rispetto’. The ferma was the proper period of active service, which could be expanded to the following six months in case of need; the months of di rispetto, instead, was a period during which the Condotta. acted as a sort of ‘strategic reserve’ and had to remain at the disposal of his employer to be ready for service in case of need.

In time of peace, another kind of contract could be signed by the Condottieri: this was known as ‘condotta di aspetto’ and prescribed the payment of just a third or half pay in exchange for the promise of a Condottiero to keep his men available and ready for service just in case. In practice, the condotta di aspetto was a way to transform the Compagnies di ventura into something more stable, in time of peace. Initially this kind of contract was not particularly popular but, since it was possible for a Condotta to fight in active service for a second employer whilst being on reserve service for a first, the condotta di aspetto started to be used on a larger scale.

It is notable that during the Renaissance an increasing number of Condotte started to sign longer and more stable contracts with various Italian states with the result that larger bodies of mercenaries started to gradually transform themselves into modern, standing armies serving a single Signoria on a stable basis. During the final part of the Renaissance, all the Italian armies started to comprise an increasing number of ‘standing’ military units that received a fixed pay (‘provvisione’) on a regular basis. These corps, which usually made up the personal guards of various Italian rulers or acted as garrison troops, were called ‘Provvisionati’ and had better equipment/training if compared to most of the standard Condotte.

Several of the Condotte already had elements that were quite modern for their age, however. The most important Condottieri had their own ‘Casa’ or ‘Household’ which comprised a marshal, chancellors, cooks, chaplains, military musicians and a mounted escort.

Italian armies of the Renaissance were mostly made up of heavy cavalrymen; infantry, in fact, was only a secondary component of the military forces deployed by each Signoria. This factor represented a serious drawback for many Italian states when the foreign armies of France and Spain invaded their territories with large forces of professional infantrymen. Generally speaking, each Condotta did comprise a limited number of infantrymen but they only had auxiliary roles.

Most of the Signorie did continue to field some contingents of urban militia during the Renaissance period: these consisted of infantrymen and were still organized according to the old systems of the Comuni. The foot militiamen were badly equipped and poorly trained, but could be deployed in great numbers in case of military emergency, however, in time all of the militia systems of the Italian states were completely reformed and greatly expanded to face new military threats from foreign powers. The quality of the infantrymen was improved, but they remained a secondary element in the Italian military system and never reached the same standards of service as the professional foot soldiers from outside Italy.

The innovations from the Renaissance were felt in every field of knowledge, including in the art of war. It was during the Renaissance that heavy cavalry lost its prominence on the battlefield due to the ‘infantry revolution’ that took place during the Italian Wars and that the idea of ‘nation’ also completely changed with the great national monarchies of Europe transforming themselves into proper ‘modern states’ of professional standing armies and complex systems of administration.

Renaissance Armies in Italy 1450–1550 is available to order from the website now!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment