As modern warfare has changed the nature of armed conflict, reconnaissance (both operational and tactical) has been given ever-increasing importance.

Essential decisions, such as the location or timing of a military operation, required good preparation. The same was true for any unit in the field exposed to the danger of a surprise and potentially devastating attack.

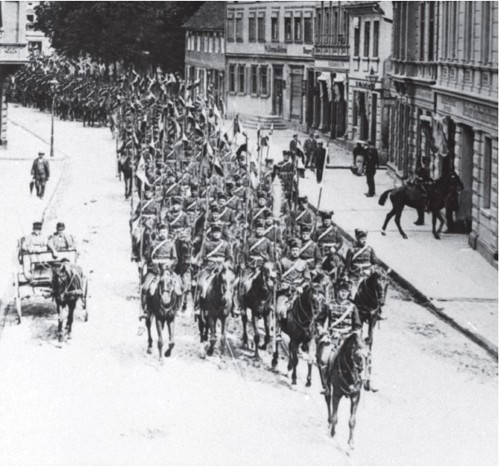

In the mid-1700s, Hussars came to be used as light cavalry in almost every army in Europe. Their superior speed meant that they were regularly used for reconnaissance. When led by intelligent and determined leaders, Hussars were also expected to fulfill limited combat missions, for example, disrupting enemy lines of supply or performing surprise attacks into their rear positions.

These cavalry units can, with some reservations, be considered as the forerunners of modern tactical reconnaissance. After the Napoleonic Wars, the Hussars were absorbed into a largely standardized cavalry. In many armies of Europe, the regiments were to be nominally preserved with their original names as part of maintaining tradition.

In the 1920s, the Reichswehr began to receive a small number of wheeled personnel carriers. These unarmoured vehicles (SdKfz 3) were assigned to the newly formed Kraftfahr-Abteilungen (KfzAbt – motorized battalions) and used for troops to learn the battlefield tactics to be employed by a mobile army. But, despite having all-wheel drive, the SdKfz 3 had very limited off-road performance.

In the 1920s, the Reichswehr began to receive a small number of wheeled personnel carriers. These unarmoured vehicles (SdKfz 3) were assigned to the newly formed Kraftfahr-Abteilungen (KfzAbt – motorized battalions) and used for troops to learn the battlefield tactics to be employed by a mobile army. But, despite having all-wheel drive, the SdKfz 3 had very limited off-road performance.

The Hussar regiments, like the Dragoon regiments, were now combat troops equipped with rifles, capable of fulfilling a wide variety of missions. In Germany, first to be assigned to infantry divisions in squadron (company) strength as dedicated reconnaissance units during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871). Even then, there was always the danger that army commanders would use the strong mobile units as mounted infantry and quickly wear them out.

The combat value of cavalry tasked with reconnaissance is indisputable. In the early 1900s, technical progress was to have a slow but lasting influence on the general conditions and operational principles of the troops. In the United States of America, Great Britain and Austria, reconnaissance units were equipped with motor vehicles for the first time; some were already armoured and equipped with light weapons.

In World War I, tactical reconnaissance was still the task of horsemounted units; the Hussars were considered to be the specialists. But the deployment of such a unit on what became a static battlefront made little sense.

In the German Reich, the influence of a conservative and, in many ways, backward general staff initially prevailed. Changes, such as the introduction of the motor vehicle, were implemented with significant hesitancy. This was noticed at the beginning of World War I, when cars and trucks were used mainly for the transport of supplies or as tractors for the increasingly heavy artillery. But this was to change as the war progressed. Both Great Britain and France invested large resources in the introduction of gun-mounted armoured vehicles. Whereas, the German Reich lacking finance and industrial resources was slow to respond.

After the end of the war, any momentum in Germany was slowed due to the strict restrictions imposed on the Reich under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. These were demanded by France in particular, in order to weaken the former enemy decisively and for the long term. The restrictions outlawed the possession of heavy weaponry and prohibitied any development work; this was also applied to not only warships, but also tanks and wheeled armoured vehicles. The ‘100,000-man army’ was only allowed a total of 100 obsolete machine-gun carrying armoured cars to equip the seven Kraftfahr-Abteilungen (KfAbt – motor battalions). These vehicles, built by various manufacturers, were only suitable for police duties since they were not designed to be crosscountry capable. During the fight against the radical left-wing uprisings in Germany from 1919 to 1920, these armoured vehicles proved to be of great value despite their limitations. However, these vehicles did not meet the requirements of later military conflict. In the 1920s and 1930s, many essential tasks in the German army, including reconnaissance, would continue to be performed by horse-mounted units.

Despite the obvious technical disadvantages of the early armoured cars, Daimler- Benz was to develop a ‘gepanzerter Kraftwagen für Mannschaftsbeförderung’ (armoured motor vehicle for personnel transport) in 1927 and build it in limited numbers (20 to 40 depending on the source). These were standardized as Sonderkraftfahrzeug (SdKfz – special-purpose vehicle) 3 and built on a simple two-axle chassis with all-wheel drive and solid rubber tyres. Designated as a Mannschafts-Transportwagen (MTW – personnel carrier), the large, lightly armoured vehicle could carry of up to 14 troops, but no armament.

During the 1930s, there were three cavalry divisions, and all carefully nurtured and retained

their traditions. With the build-up of the Wehrmacht, they were to be absorbed into other units with 3rd Kavellerie Division (3.KavDiv – cavalry division) forming the core of 1st Panzer Division (1.PzDiv).

The SdKfz 3 still served in the provisional motorized divisions in the first year of World War II and was recognizable by the large frame-type antenna for the two-way radio equipment.

Of similar design was the Sonderwagen (special vehicle) – known as the ‘SchuPo’ – produced for the Schutz-Polizei (security police) and built by Daimler as the DVRZ 21; Benz/21 (VP21) and the Ehrhardt/21. Unlike the Kraftfahrzeug (Kfz – motor vehicle) 3 the type had two rotatable turrets, each mounting a 7.92mm Maschinengewehr (MG – machine gun) 08/15, positioned on the top of the superstructure. It is thought that some 55 entered service in the 1920s, but all had been phased out by 1936.

If you enjoyed today's post you can find out more in Panzer Reconnaissance.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment