In the post-1918 era the United States faced the prospect of a war with the Japanese Empire in the western Pacific, specifically the problem of defending the Philippine Islands. With the bulk of the US Navy located in home waters, a fleet would have to traverse the Pacific to defend the Philippines and establish naval control of the Western Pacific. This fleet required anchorages and facilities across the Pacific to enable refueling, resupplying, maintenance, and light repairs. Following World War I, Japan received control of Central Pacific islands that had been ruled by Imperial Germany. These islands could be used to interdict the American route to the Philippines through Micronesia. Micronesia includes the Mariana, Palau, Caroline, Marshall, and Gilbert Islands. Capturing and defending small islands and atolls would be required to enable the US Navy to advance to the Philippines.

After the failure of the Gallipoli operation in World War I, many military commentators proclaimed that amphibious assaults were no longer possible. However, faced with the problem of reaching the Philippines in wartime, the US Navy and Marine Corps began studying how to seize and defend islands in the Central Pacific. Concepts were developed and incorporated in the Joint Army–Navy plan for war against the Japanese Empire. This plan was known as War Plan Orange. The Marine Corps decided that the problem was one of doctrine and technology. Lacking a sufficient doctrine, the Corps intently studied the subject. In the forefront of the initial work was Major Pete Ellis USMC, who wrote a study titled Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia. In this, Ellis assessed possible islands and atolls to be seized, estimated likely enemy defenses and American landing forces needed for different objectives. Ellis identified key factors for successful ship-to-shore assaults including disembarkation of troops from transports into landing boats, organization and control of landing boats as they advanced toward the beach, composition and equipment of combat teams to conduct assaults, roles of air and naval gunfire support, intelligence, and communications.

Ellis’s work became the foundation upon which the Marine Corps began to develop amphibious warfare doctrine. In November 1933, the Marine Corps Schools at Quantico, Virginia, suspended classes and put all hands to work writing a detailed doctrine for amphibious operations. The resulting document, Tentative Manual for Landing Operations, was issued January 1934. In 1935 an updated version was issued by the Navy under the Title Tentative Landing Operations Manual. Another revision was issued in 1938 as Fleet Training Publication 167 (FTP-167) Landing Operations Doctrine, which became US amphibious warfare doctrine throughout World War II. The manual stated that in an amphibious assault, ship to shore movement was an integral part of an infantry attack: ‘A landing operation against opposition is, in effect, an assault on an organized or unorganized defensive position modified by substituting initially ships’ gunfire for that of light, medium, and heavy field artillery, and frequently, carrier-based aviation for land-based air units until the latter can be operated from shore.’

At 0832hrs, November 20, 1943, Landing Vehicle, Tracks (LVTs) carrying the 2d Marine Regiment crossed their line of departure off shore of Betio Island of Tarawa atoll in the Gilbert Islands, reaching the beach 45 minutes later. The ensuing 76 hours of intense combat resulted in the US capture of Betio. This assault was a brutal combat test of US amphibious warfare doctrine, organization, tactics, and capabilities. The fighting was barely over when the Navy and Marine Corps began a systematic evaluation of all aspects of the operation. As a result of Tarawa, Navy leadership decided that ships must get as close as possible to the shore during preparation bombardments and while firing in support of troops during the ship-to-shore assault. Now destroyers closed the beach and relied on observing the progress towards the beach of assault waves before lifting their fires off the beach. Battleships were expected to get within 1,000 yards or less of the beach to deliver pinpoint shelling instead of cruising miles offshore blindly shelling geographical areas. Captains of fire-support ships received new orders regarding their ships. Before the invasion of the Marshall Islands Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner decreed; ‘I say to you commanders of ships – your mission is to put the troops ashore and support their attack to the limit of your capabilities. We expect to lose some ships! If your mission demands it, risk your ship!’ Tarawa’s capture was followed in February 1944 by the rapid seizure of Kwajalein and Eniwetok atolls in the Marshall Islands where lessons learned and new procedures were put to work and subjected to the test of combat, after-action assessment, and improvement. The pioneering work of a dedicated handful like Pete Ellis made the post-Gallipoli assertions of the end of amphibious warfare another example of ill-founded military assertions.

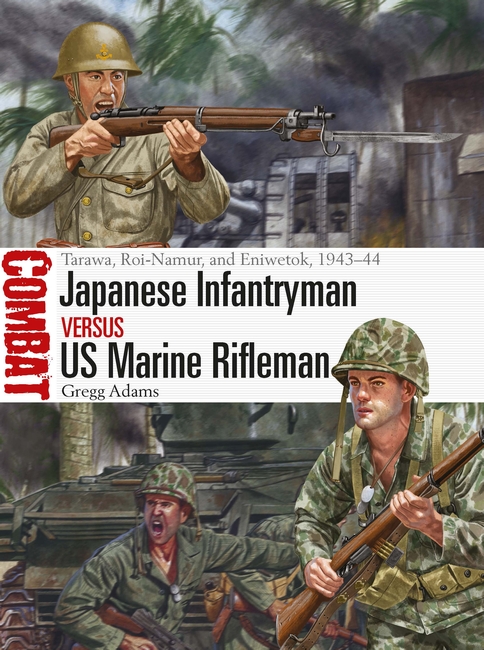

Combat 75, Japanese Infantryman versus US Marine Rifleman: Tarawa, Roi-Namur, and Eniwetok, 1943–44, examines the development of American amphibious doctrine and its employment against Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces, IJN guard troops, and the Imperial Japanese Army on coral atolls of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands. Japan’s doctrine for defending islands is examined and its failure when lacking the support of the Imperial Japanese Fleet illustrated. This work shows that the strength and effectiveness of US forces in the Pacific rendered most Japanese island garrisons superfluous to the war. Many fortified Japanese-held islands in the Central Pacific were bypassed and isolated by the Americans as the war moved westward towards Japan itself.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment