“Not Until the Men Who Fought and Fell on Culp’s Hill Receive the Credit Due Them Will Justice Be Done”: Reinterpreting the Meaning of Day Three

In September 1883, more than 20 years after the Battle of Gettysburg, veterans from three Pennsylvania regiments—the 28th Pennsylvania, the 147th Pennsylvania, and Independent Battery E—journeyed to Gettysburg to mark the locations their units had occupied on July 3, 1863. According to newspaper reports, the veterans experienced little trouble rediscovering the ground.

All three regiments had been part of the Army of the Potomac’s 12th Corps, the corps that had occupied the wooded slopes of Culp’s Hill, and, generally, this group of veterans shared similar memories of the battle. Upon returning to the field, they discovered that Culp’s Hill had barely changed. The places where they had once stood still looked eerily familiar, and the remnants of their crumbling earthworks could still be recognized. So it seemed, the 12th Corps veterans could never forget what the ground looked like. The engagement at Culp’s Hill had forged one of the prevailing memories of their military careers. Over the course of the afternoon, the Pennsylvania veterans drove a series of stakes into the ground (blue for the infantry regiments and red for the artillery battery), to identify the lines they had held on July 3. At the time, they were in the process of raising money to erect permanent granite markers. These memorials arrived only a few years later. The 28th Pennsylvania’s monument appeared in 1885, and monuments for the other two units appeared in 1889.

Veterans from the 28th Pennsylvania gather on Culp’s Hill on September 12, 1889. (Courtesy of the Geary Guard)

If any tension existed among them, it was reflected in the words of Corporal Joseph Asher Lumbard (formerly of the 147th Pennsylvania) who delivered the reunion’s keynote address. In 1863, Lumbard had been 19 years old. Now, at age 39, he narrated the happenings of that fateful day to an audience of veterans and their families. Lumbard wanted everyone in attendance to know that the fighting endured by the 12th Corps had been the roughest of the entire battle. Not only had the morning battle for Culp’s Hill lasted over five hours, but it had been carried on by two determined foes. Lumbard said:

“This contest lasted from 5 until nearly 10 A.M., and at no place along the line was any more determined attempt made [by the enemy] or one that lasted as long. These are facts. You can all attest the correctness of my assertions. And had our division been driven from Culp’s Hill, the celebrated charge of Pickett’s division would never have been made. To the eye of any man acquainted with military strategy, it is plainly evident that in an attack the enemy could easily advance upon us here. The formation gave them ample opportunity to approach within one hundred yards before our fire could reach them, and once formed, they could, in a short space of time, charge into our lines; and the fact that men were bayoneted immediately outside our temporary works attest to the severity of the struggle and the determination of the enemy in our front.”

Thus, Lumbard reached his thesis. Not only had the July 3 fight at Culp’s Hill produced Gettysburg’s most harrowing combat, but according to him, it was also the most consequential action of the three days. At Culp’s Hill, the Army of Northern Virginia possessed its best opportunity of driving the Union troops from their defensive positions. Had the rebels been successful, they would have overrun Culp’s Hill, carried the Baltimore Pike, and forced the Army of the Potomac to retreat. At Culp’s Hill, claimed Lumbard, the scales of victory had reached their slimmest margin of error, and for that reason, the nation needed to show gratitude to soldiers who “wore the Star,” a reference to the 12 Corps’ unique star-shaped identification badge. Lumbard concluded:

“I have narrated facts as they existed, and no one can truthfully say that any troops of this admirably fought battle displayed more bravery or fought with greater determination than did the heroes of the Star, and not until the men who fought and fell on Culp’s Hill receive the credit due them will justice be done one of the bravest corps of the noble old Army of the Potomac.”[1]

Joseph Asher Lumbard delivered the reunion address on Culp’s Hill in 1883. (The Snyder County Tribune)

Surely, everyone in the friendly audience agreed Lumbard’s words. The 12th Corps veterans felt immense pride in what they had accomplished on the morning of July 3, and, at his point in their lives, they jealously defended that pride to the American public. In their opinion, another sector of the battlefield was already receiving undue attention: Pickett’s Charge. For the past 20 years, amateur historians and newspapermen including Edward Pollard, Charles C. Coffin, and William Swinton had focused the nation’s attention to July 3’s afternoon engagement, the grand attack made by George Pickett’s, Johnston Pettigrew’s, and Isaac Trimble’s divisions against the Union center. Already, military artists including James Walker and Peter Rothermel had completed grand canvas paintings of Pickett’s Charge, lofting it deeper into the memories of Americans. Among many examples, Walter Harrison’s 1870 book, Pickett's Men: A Fragment of War History, encapsulated the idea that Pickett’s Charge represented the “high tide” of Confederate hopes. When concluding his tale about the retreat of Pickett’s division, Harrison stated, “And thus this day’s fight, so brilliantly begun for the Confederates, so important in the history of the war, so crushing in its effects to the whole Army of Northern Virginia, was ended. Yes, practically ended. For the rest was but the getting out of a bad scrape in the best manner possible; and there was no best about it.”[2]

Thus, in the two decades after the war, Pickett’s Charge became the climax of Gettysburg’s story, and it remained that way for the next 100 years. Perhaps, even today, most Americans still believe Pickett’s Charge represented the battle’s climax. When my father took me on my first visit to Gettysburg in 1987, Pickett’s Charge was the only event that I had heard of prior to going, and it was the first locale we sought out. Try as I might, I cannot remember the first time I ever visited Culp’s Hill. The trip there did not resonate the same way as my first visit to Pickett’s Charge. At the time, Culp’s Hill carried neither the cache of being the bloodiest fight nor the reputation for being the most important clash of arms. Indeed, the National Park Service auto-tour brochure map did not help matters. Even during the years that I worked as a seasonal ranger, the tour discouraged visitors from heading to Culp’s Hill. The brochure of the 1990s and 2000s recommended first-time visitors to take a two-hour driving tour, but only if they had three or more hours to devote the field, then they could drive to Culp’s Hill as part of the “optional route.”

For years, I supported this commonly held belief: the battle’s outcome was decided by the failure of Pickett’s Charge to break the Union center. Indeed, even as I became more interested in the battle academically, my interest in Culp’s Hill only continued to wane. In college, I read Gary Gallagher’s 1994 book, The Third Day at Gettysburg and Beyond, which contained six essays written by acclaimed historians, but none of them—not a one—discussed the engagement at Culp’s Hill. Predictably, three of the essays emphasized Pickett’s Charge. To me, unconsciously, the lack of coverage of Culp’s Hill in Gallagher’s book only further reinforced the idea that the infantry assault against the Union center constituted the bulk of the third day’s fighting.[3]

But all this changed in 2000, about one year after I started working for Gettysburg National Military Park. That year, a college friend introduced me to a collection of letters kept at our campus Special Collections Archive. The letters belonged to a 12th Corps soldier, Sergeant Ambrose Henry Hayward of the 28th Pennsylvania. I greatly enjoyed reading Civil War soldier letters (and I still do). I especially loved the opportunity to read the letters in their original form, and that proved to be the case in this particular instance. I loved Hayward’s letters for several reasons, but among many aspects that intrigued me, was the incredible pride Hayward took in the part played by his regiment in the defense of the Union right flank at Gettysburg. Just three days after the battle, in a flurry of excitement, he wrote to his father, “it will be enough for you to know that I have done my duty in the last great Contest and have not received a scratch. our Division met the famous Stonewall Division and repulsed them in all their onsets.” A week later, apparently still basking in the glow of the victory, Hayward asked his father, “what do the people of the North think now of the Old Army of the Potomac[?] have they not proved to the world that it has not been their fault that they have not won fields before[?]”[4]

Sergeant Ambrose Henry Hayward, 28th Pennsylvania. (MASS-MOLLUS Collection, Army Heritage and Education Center)

It intrigued me to see a Union soldier from the 12th Corps exhibit such immense vanity in what I had always considered an unimportant sideshow to the story of Day 3. In placing Culp’s Hill’s morning engagement into the historical dustbin, I worried that I had missed something important. Hayward’s letters seemed to be encouraging me to break loose from my assumptions about Day 3 and explore the tale of Culp’s Hill anew. Eager to take advantage of an opportunity to learn more about this, one of the battlefield’s least visited areas, I asked my supervisor at Gettysburg National Military Park if I could add a new program to my repertoire. In those days, GNMP offered an hour-long program that focused on the fighting at Culp’s Hill. It was not a popular program. It occurred only three times per week, and generally, it did not get heavy visitation. Younger seasonal rangers such as myself rarely asked to take it on. But with my imagination stoked, I decided to create my own Culp’s Hill program. Scott Hartwig, my supervisor, authorized me to do it.

In putting my story together, I realized that Sergeant Hayward was not the only 12th Corps soldier who believed that Culp’s Hill forged the turning point of the battle. In fact, most Union survivors from the 12th Corps described the morning engagement at Culp’s Hill the same way he did. One month after the battle, Sergeant Fayette Hale (a soldier in the 123rd New York) wrote to his local newspaper, proclaiming that “the severest fighting” had been done on this part of the field. He continued, “This was the time when ‘Greek met Greek.’—The field of Gettysburgh for many centuries, will be redolent with historical reminiscences and sacred beyond any soil made red with the blood of freedom’s martyrs since the opening of the ‘Great Rebellion.’” Another soldier, Private DeRoy Eldredge of the same regiment, spoke with the same sense of hyperbole. He doubted “if Napoleon’s campaign before Moscow was much harder” than the fighting he had endured.[5]

For decades, the 12th Corps soldiers remained on the proverbial warpath. Thirty-seven years later, Lieutenant Colonel Eugene Powell—the commander of the 66th Ohio—wrote a lengthy article for a veteran’s newspaper, The National Tribune. It bore the title: “Rebellion’s High Tide: The Splendid Work the Third Day on Culp’s Hill by the Twelfth Corps.” Like others before him, Powell emphasized the defense of Culp’s Hill. Most notably, Powell could not shake from his mind the sight of Culp’s Hill’s grisly aftermath:

“Probably no battlefield ever presented more evidences of a severer struggle than did that part between our fieldworks and Rock Creek. The face of the space that the enemy had advanced over was very rough, covered with rocks, logs and forest trees; these afforded shelter to the enemy and were thereby made objects of our wrath, and upon which we vented our vengeance in hopes of striking the men behind them, and for two days and nights volleys of lead and iron were hurled from foe to foe until bodies of trees of large size were actually cut in two by these missiles, and falling with their outspreading branches upon the living or dead beneath buried them, for a time, as in a sepulcher; the faces of the rocks fronting these foes were marred and battered by bullets until a line of dead lay in a shapeless heap beneath. Logs were splintered and torn, so as no longer to afford shelter to human beings. The earth alone was proof to against that carnival of destruction, as the seams and rents made in its surface were willed by the dirt and dust falling back into them, and the sears and rents thus made soon became imperceptible.”[6]

Some soldiers from the 12th Corps chose to comment on the sight of the enemy dead, who littered the slopes of the hill by the thousands. Lieutenant Samuel B. Wheelock, an officer in the 137th New York, told his local newspaper, “The spectacle was hideous. The ground was strewn with the bodies of the dead, with a few from which life had not yet departed. The number of victims bore undisputable testimony to the cool and accurate firing of our men.”[7]

Lest my readers get the wrong idea, it should be stated that few 12th Corps veterans—if any—denigrated the combat that occurred on other parts of the battlefield. They did not run down or dismiss what had been achieved by the Army of the Potomac’s other corps. Understandably, the 12th Corps veterans tried to draw attention to their part of the field, but they bore a sense of humility about it, stopping far short of detracting from the accomplishments of others. For instance, Color Corporal John M. Vallean of the 109th Pennsylvania told the media that members of his regiment “do not claim to have done more than other regiments who helped to defeat Lee.” However, over the years, Vallean and his comrades felt great annoyance to learn that veterans from other regiments were taking too much glory at the expense of those who fought on Culp’s Hill. He claimed, “We never had a newspaper reporter to boost us at home, nor political tricksters to pull the wires for promoting favorites; but we knew regiments that had and whose officers stole the thunder that belonged to more deserving men.”[8]

Although only a few historians took their cues from the letters and memoirs of the 12th Corps veterans, those who did left behind a well-researched trail for me to follow. When creating my Culp’s Hill program back in the 2000s, Harry Pfanz’s book, Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, influenced me heavily. Pfanz, the longtime Chief Historian of the National Park Service, had crafted a stunning narrative of the fighting on the Union right. His book did not actively seek to create a thesis about Culp’s Hill, but one subtly emerged nonetheless. Near the end of his book, Pfanz concluded, “The Culp’s Hill fight was a disaster for the Army of Northern Virginia. Its casualties far exceeded 1,823 reported by Johnson’s division … and nothing was gained. When the fighting ended late on the morning of 3 July, the Union line was intact and held more strongly than before…Hindsight tells us that the Confederate assault of 3 July on Culp’s Hill was a tragic waste.” [9]

My supervisor, Scott Hartwig, had even greater influence. In truth, he had a stronger opinion about Culp’s Hill, one that went beyond what Pfanz had claimed in his book. After I had performed my Culp’s Hill tour a few times, Scott came out to see it and to offer feedback. Significantly, he suggested that I emphasize the reasons why Culp’s Hill mattered more to the Union defense than any other terrain feature. “You can see the importance even from where we stand,” he told me. “We’re only 500 yards from the Baltimore Pike, the only macadamized road in Adams County. If the Confederates get a hold of that, then it’s game over for Meade. He has to retreat. He has no other choice!”

Scott Hartwig, my supervisor at GNMP. (Courtesy of Scott Hartwig)

I let those words sink in. Thanks to the 12th Corps letters, Pfanz’s book, and Scott’s feedback, it became clear to me why the Confederates had charged so recklessly against the Union earthworks. They knew how close they had come to winning a victory on July 3. They were within easy reach of the truly pivotal physical feature upon which the Union army’s defense hinged: its line of retreat. If the Baltimore Pike fell, the battle was over for the bluecoats. The Confederates had a tough chore in front of them. They had to drive out a veteran corps, the 12th, and to do that, they had to attack up the slopes of Culp’s Hill and overrun the earthworks. Only a truly desperate attack could achieve such an outcome. That desperation had not gone unnoticed by the 12th Corps soldiers who had to repulse them, and it went a long way to explaining why, until their dying day, the 12th Corps veterans felt slightly aggrieved that their sector of the battlefield had not been called the “high water mark.” Perhaps Pickett’s Charge rivaled the Culp’s Hill attack in terms of its grandeur, but if Pickett’s Charge was a “high water mark,” then so too was Culp’s Hill.

Taken 20 years ago, this photograph depicts me leading a tour at Culp’s Hill. (Courtesy of author)

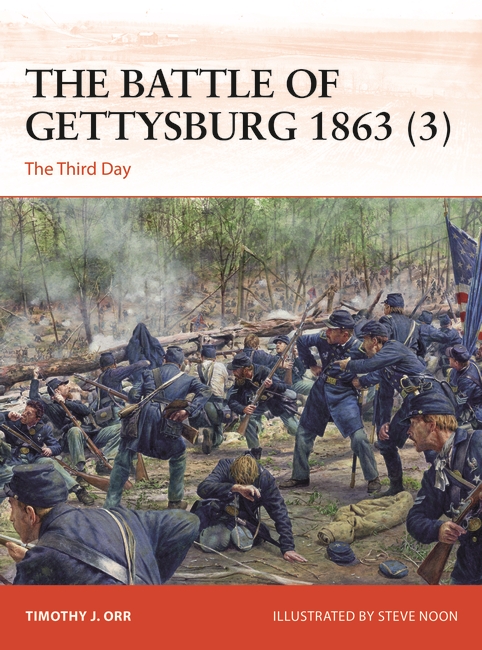

Thus, another 20 years later, I’m delighted that Steve Noon’s superb illustration depicting the Union defense of Culp’s Hill adorns the cover of the final volume of our Gettysburg trilogy. Steve and I worked tirelessly on this one, depicting Culp’s Hill as it appeared in 1863. Since the days when the veterans visited in the 1880s, this area of the battlefield has become overgrown, making the original landscape difficult to discern. But after long hours studying the topography, the earthworks, the vegetation, and the uniforms of the rival forces, I think we’ve put together something special. Successfully, Steve’s illustration captures a scene from behind the 12th Corps earthworks. Viewers stand with the soldiers of the 7th Ohio as they poured volley after volley into the last attacks made by Major General Edward Johnson’s division. Down the slope, men from the Stonewall Brigade raise their hands in surrender, and sharp-eyed viewers might spot Major Benjamin W. Leigh, a Confederate staff officer who tried to stop the surrender from occurring, an act which earned encomiums from Union soldiers who watched from above as Leigh was cut down by rifle fire.

Steve Noon’s illustration of the Culp’s Hill fight.

Moreover, viewers will see the grittiness of this fight, the sweat and exhilaration upon the faces of the 12th Corps soldiers, the wearers of the Star, as the Confederate attack reaches its climax. I would never go so far as to say that the sacrifices of the 12th Corps were more important than those of their comrades elsewhere, but, I think, in bringing their story to the forefront (indeed, to the front cover of our book), we’ve made a valuable contribution to their memory. As they faded from the limelight, the 12th Corps soldiers worried their sacrifices would be forgotten. Perhaps now, first-time visitors will be more likely to pay Culp’s Hill a visit and reflect on the importance of what they did.

This veteran from the 12th Corps is unidentified. Note the star-shaped badge on his frock coat which identifies his corps. (Library of Congress)

Find out more in the book here.

[1] National Tribune, September 20, 1883.

[2] Walter Harrison, Pickett’s Men: A Fragment of War History (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1870), 99.

[3] Gary Gallagher, ed., The Third Day at Gettysburg and Beyond (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1994).

[4] Ambrose Henry Hayward to father, July 6 and 17, 1863, in Timothy J. Orr, ed., Last to Leave the Field: The Life and Letters of Sergeant Ambrose Henry Hayward, 28th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2010), 158–159.

[5] New York State Military Museum, Unit History Project: https://museum.dmna.ny.gov/unit-history/infantry-2/123rd-infantry-regiment.

[6] National Tribune, July 5, 1900.

[7] New York State Military Museum, Unit History Project: https://museum.dmna.ny.gov/unit-history/infantry-2/137th-infantry-regiment.

[8] National Tribune, May 9, 1901.

[9] Harry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg – Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill (Chapel Hill: University Press of North Carolina, 1993), 352.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment