One of the striking features of Russia’s current war in Ukraine is that it is often, perhaps inaccurately, described as a “mercenary war” because it is being fought not by conscripts serving out their national service, or even reservists summoned back to arms, but by volunteers. Attracted by what are often life-changing sums of money, including salaries some three and a half times the national average, hundreds of thousands of Russians, predominantly from the poorest regions of the country, have signed contracts committing them to fight for the duration of Vladimir Putin’s so-called “Special Military Operation.” Quite whether they deserve to be called “mercenaries” is open to question; all professional armies are, after all, recruited with the promise of competitive pay and the like. However, the war also saw the rise and then precipitous fall of a genuine mercenary army, the Wagner Group, raised and managed by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a criminal, businessman and contact (though never friend) of Putin’s, who eventually launched a doomed mutiny that, in turn, led to the effective “nationalization” of Wagner and his own death in a not-so-mysterious plane crash.

Writing Putin's Mercenaries, 2013–24, it became clear that, while there is a long pedigree of Russia drawing on mercenaries, there was also something distinctive about Wagner that shone a light on how modern Russia works (and how it often doesn’t). The evolution of the Russian military over the centuries has frequently been shaped by mercenaries, typically foreigners. When facing highly mobile horse nomads from the steppes in the pre-tsarist era, the eleventh- and twelfth-century princes of the Rus’ recruited their own, the Turkic Chyornye Klobuki, or “Black Hoods.” Later, the Cossacks, a society of mixed ethnic origin that emerged primarily in the early fifteenth century from the “Wild Fields,” the much-raided lands between Poland-Lithuania, Muscovy, and the Crimean and Kazan Khanates, would become essential light cavalry, and also spearhead Muscovy’s expansion eastward, through Siberia and into the Far East.

The mercenaries were often specialists in techniques and technologies that Russia needed in order to fight the more advanced enemies to the west, especially the Swedes and the Poles. The Italian architect and military engineer Ridolfo “Aristotele” Fioravanti not only designed the red-brick walls of the modernized Moscow Kremlin for Ivan III, he also founded the Cannons’ Court, the country’s first site for the systematic production of artillery. Russia’s emerging navy would generate a particular need for foreign expertise. Ivan IV – Ivan the Terrible – deployed a small flotilla marauding in the Baltic under a Danish privateer, but it was Peter the Great who really built the Russian navy, especially with English and Dutch sailors and captains. Indeed, this was a practice which would survive into the eighteenth century: the “Father of the American Navy,” John Paul Jones, briefly served Catherine the Great as a Rear Admiral of the Black Sea Fleet, playing a key role in the Russian victory over the Turkish fleet in 1788.

Peter also turned to foreign mercenaries to Europeanize his army. All of his eight original “New Style” infantry regiments were at first led by foreigners: Germans, Scots, Scandinavians, English, and Dutch. Many famous Russian families sprang from foreign mercenaries who settled. The Lermontovs, for example, who numbered amongst their line Mikhail Lermontov, one of the greatest nineteenth-century authors of the Russian canon, trace their origins back to one George Learmonth, a Scottish mercenary from Fife who eventually converted to the Orthodox faith and adopt the Russified name Yuri Andreevich Lermont.

The later imperial military would largely abandon the use of mercenaries, as would the Bolshevik regime (once past the chaos of the Russian Civil War), even if the Soviets did use proxies such as Cuban troops for power projection into Africa during the Cold War. However, Putin’s Russia is in many ways an odd hybrid of statism and free-market free-for-all, and has turned to outsourcing all kinds of activities, from spreading disinformation (Prigozhin was also a provider of ‘troll factories’ pumping out propaganda on social media) to persecuting dissidents.

The origins of Wagner could be traced back to 2010, when Eeben Barlow, founder of the South African military company Executive Outcomes, gave a presentation at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. Gen. Nikolai Makarov, then the chief of the General Staff, was reportedly enthused by the notion that a suitable private military company (PMC) could be used for political–military operations beyond Russia’s immediate strategic neighborhood. In 2012, one was founded, the Slavonic Corps, but its first deployment, to Syria, was such an ignominious failure that it was quickly wound up, and its principals arrested. But the goal of a PMC that could be at once a commercial, profit-making venture and, when the Kremlin wanted, also a deniable instrument abroad survived. In 2013, it decided to create a new force, and essentially strongarmed Prigozhin – who was reluctant, but knew he couldn’t afford to refuse – into being its manager and public face. Needing an experienced field commander, Prigozhin turned to a recently demobbed former Spetsnaz (special forces) lieutenant colonel, Dmitry Utkin, who had previously commanded the 2nd Brigade’s 700th Detachment. Utkin was, as one newspaper coyly put it, “an aficionado of the aesthetics of the Third Reich.” In other words, he was a neo-Nazi, with SS lightning flashes tattooed on his shoulders and a Nazi eagle on his chest – and his callsign in the Spetsnaz had been Wagner, after Hitler’s favorite composer, and this is how the new PMC got its name.

What followed was a mix of ups and downs, with early successes in Syria followed by a disastrous defeat at the hands of American forces (likely with the tacit approval of a jealous local Russian regular military command), partnerships with authoritarian regimes in Africa, and then a hurried deployment to Ukraine once the initial invasion had stalled. This would lead to the massive expansion of Wagner, not least by starting the practice of recruiting from prisons, and equally massive losses in the meatgrinder of a battle for the city of Bakhmut. Increasingly outflanked by then-Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, Prigozhin’s futile mutiny in 2023 was not a bid to topple Putin so much as a last-ditch attempt to persuade him to back Wagner against Shoigu, as the ministry sought to take control of the mercenaries.

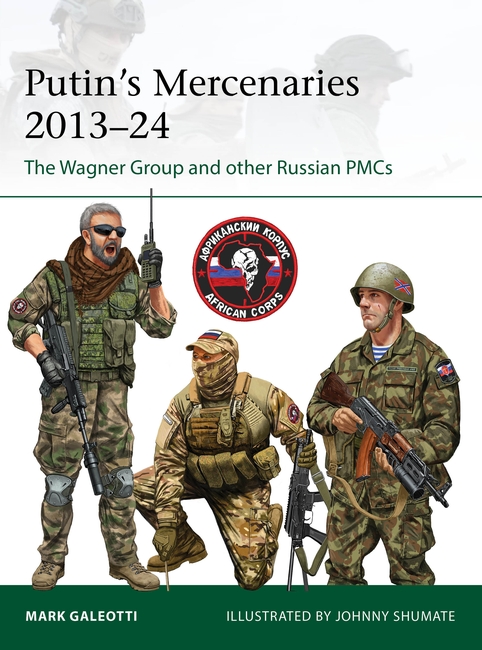

Of course, the mutiny failed, and Wagner was ultimately broken up and brought under tighter military control. In Africa, it has been almost entirely folded into a new force with the historically jarring name of the Africa Corps. Elsewhere, Wagner fighters were brought into other units, all now part of the Expeditionary Volunteer Assault Corps, an umbrella formation for a variety of units, from reservist battalions to units raised by state corporations, yet all under regular military control. For now, it is clear that Putin has learned – like so many mercenaries’ customers through history – how hard it can be to control them.

Yet at the same time, there is still a strong sense in which his regime relies on outsourcing its warfighting, from the use of North Korean troops to Chechen “Kadyrovtsy” who notionally obey Moscow but swear oaths of personal fealty to Chechen warlord Ramzan Kadyrov. Russia also has turned increasingly to proxies and hirelings instead of its own agents to stir up trouble in Europe. There is a strong sense that as and when the Ukraine war ends, the Kremlin will not have given up on making conflict a public-private venture.

You can read more in Putin's Mercenaries, 2013–24: The Wagner Group and other Russian PMCs

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment