The following extract is taken from The First World War: The War to end all Wars by Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes & Michael Hickey.

The incident that finally ignited the flames of war in Europe occurred on 28 June 1914, when, during an official visit to Sarajevo, capital of the newly annexed Austrian province of Bosnia, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austrian throne, was assassinated with his wife. The assassin, Gavrilo Princip, was one of a group of conspirators recruited and despatched to Sarajevo by the Black Hand, a Serbian terrorist group, with the connivance of the chief of Serbian military intelligence. The Serbian Government itself did not inspire the assassination but certainly knew of the plot and made well intentioned, if feeble, attempts to warn Austria about it. Austria eagerly exploited the opportunity to humble Serbia and thereby snuff out its challenge to Austro-Hungarian authority in the Balkans. First, however, Austria sought Germany’s backing for its proposed course of action. Germany, in turn, saw in the Austro-Serbian confrontation a golden chance of securing hegemony in Europe, achieving world status while splitting the encircling Entente powers, forestalling Russian modernisation, eradicating the dangers to Austria-Hungary and suffocating domestic opposition. Even though it might drag the whole of Europe into armed conflict, Germany was prepared to take this calculated risk to achieve its ends. Therefore, on 5 and 6 July Germany gave Austria a ‘blank cheque’ of unconditional support against Serbia.

The incident that finally ignited the flames of war in Europe occurred on 28 June 1914, when, during an official visit to Sarajevo, capital of the newly annexed Austrian province of Bosnia, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austrian throne, was assassinated with his wife. The assassin, Gavrilo Princip, was one of a group of conspirators recruited and despatched to Sarajevo by the Black Hand, a Serbian terrorist group, with the connivance of the chief of Serbian military intelligence. The Serbian Government itself did not inspire the assassination but certainly knew of the plot and made well intentioned, if feeble, attempts to warn Austria about it. Austria eagerly exploited the opportunity to humble Serbia and thereby snuff out its challenge to Austro-Hungarian authority in the Balkans. First, however, Austria sought Germany’s backing for its proposed course of action. Germany, in turn, saw in the Austro-Serbian confrontation a golden chance of securing hegemony in Europe, achieving world status while splitting the encircling Entente powers, forestalling Russian modernisation, eradicating the dangers to Austria-Hungary and suffocating domestic opposition. Even though it might drag the whole of Europe into armed conflict, Germany was prepared to take this calculated risk to achieve its ends. Therefore, on 5 and 6 July Germany gave Austria a ‘blank cheque’ of unconditional support against Serbia.

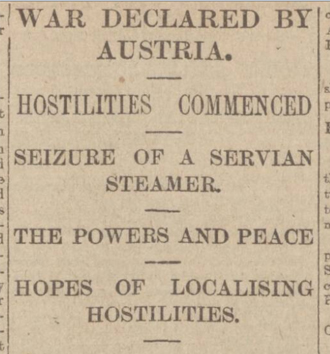

Having obtained Germany’s endorsement, on 23 July Austria issued a ten-point ultimatum to Serbia. The latter accepted nine of the points but rejected, in part, the demand that Austrian officials should be involved in the investigation of the assassination, regarding such interference as a challenge to its sovereignty. On 25 July Serbia mobilised its army; Russia also confirmed partial mobilisation before entering, on 26 July, a ‘period preparatory to war’. Austria reciprocated by mobilising the same day and then, on 28 July, declared war on Serbia. Up to this point it might still have been possible to isolate the problem, but Germany continued to act in an uncompromising manner which only served to heighten tensions and gave the crisis international dimensions. On 29 July Germany demanded an immediate cessation of Russian preparations, failing which Germany would be forced to mobilise. Russia could not afford to acquiesce meekly in the destruction of Serbian sovereignty, or increased Austrian influence in eastern and south-eastern Europe. Consequently, on 30 July Russia ordered general mobilisation in support of Serbia.

Having obtained Germany’s endorsement, on 23 July Austria issued a ten-point ultimatum to Serbia. The latter accepted nine of the points but rejected, in part, the demand that Austrian officials should be involved in the investigation of the assassination, regarding such interference as a challenge to its sovereignty. On 25 July Serbia mobilised its army; Russia also confirmed partial mobilisation before entering, on 26 July, a ‘period preparatory to war’. Austria reciprocated by mobilising the same day and then, on 28 July, declared war on Serbia. Up to this point it might still have been possible to isolate the problem, but Germany continued to act in an uncompromising manner which only served to heighten tensions and gave the crisis international dimensions. On 29 July Germany demanded an immediate cessation of Russian preparations, failing which Germany would be forced to mobilise. Russia could not afford to acquiesce meekly in the destruction of Serbian sovereignty, or increased Austrian influence in eastern and south-eastern Europe. Consequently, on 30 July Russia ordered general mobilisation in support of Serbia.

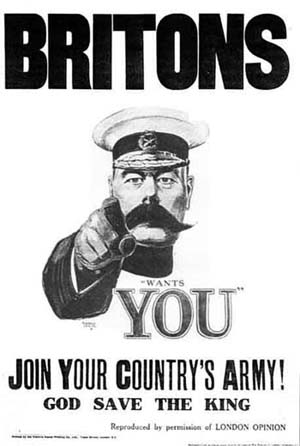

Russian mobilisation began the following day but was not the inevitable precursor to war: its forces could, if necessary, have stayed on their own territory for weeks while negotiations proceeded. Germany, however, proclaimed a Kriegsgefahrzustand (threatening danger of war) on 31 July and presented Russia with an ultimatum. Russia’s failure to respond led Germany to order general mobilisation and declare war on Russia on 1 August. This action caused France to mobilise and set in motion the remaining cogs in the intricate machinery of European alliances and understandings, for the Schlieffen Plan required, from the outset, a violation of neutral Belgium and an attack on France, quite independent of any action the Russians might take. On 2 August Germany handed Belgium an ultimatum insisting on the right of passage through its territory. This was firmly rejected and the next day Germany declared war on France. Early on 4 August German forces crossed the frontier into Belgium. The strength of the German armies on this flank was awesome. Colonel-General Alexander von Kluck’s First Army, on the extreme right, numbered 320,000 troops. The neighbouring Second Army, under Colonel-General Karl von Bülow, and the Third Army, commanded by General Max von Hausen, respectively totalled 260,000 and 180,000. The invasion of Belgian territory brought Britain into the conflict. Though it had no formal agreements with France and Russia, Britain was committed in principle, by a treaty concluded in 1839, to guarantee Belgian independence and neutrality. In 1906 the Foreign Office had observed that this pledge did not oblige Britain to aid Belgium ‘in any circumstances and at whatever risk’ but, realistically, the huge threat posed by Germany to the balance of power and the Channel ports had to be resisted. Moreover, it proved much easier for Britain’s Liberal Cabinet to rally the nation behind a war for ‘gallant little Belgium’ than behind an abstract concept such as the preservation of the status quo or the balance of power. Britain’s own ultimatum expired without reply at 11pm (London time) on 4 August and she declared war on Germany.

Russian mobilisation began the following day but was not the inevitable precursor to war: its forces could, if necessary, have stayed on their own territory for weeks while negotiations proceeded. Germany, however, proclaimed a Kriegsgefahrzustand (threatening danger of war) on 31 July and presented Russia with an ultimatum. Russia’s failure to respond led Germany to order general mobilisation and declare war on Russia on 1 August. This action caused France to mobilise and set in motion the remaining cogs in the intricate machinery of European alliances and understandings, for the Schlieffen Plan required, from the outset, a violation of neutral Belgium and an attack on France, quite independent of any action the Russians might take. On 2 August Germany handed Belgium an ultimatum insisting on the right of passage through its territory. This was firmly rejected and the next day Germany declared war on France. Early on 4 August German forces crossed the frontier into Belgium. The strength of the German armies on this flank was awesome. Colonel-General Alexander von Kluck’s First Army, on the extreme right, numbered 320,000 troops. The neighbouring Second Army, under Colonel-General Karl von Bülow, and the Third Army, commanded by General Max von Hausen, respectively totalled 260,000 and 180,000. The invasion of Belgian territory brought Britain into the conflict. Though it had no formal agreements with France and Russia, Britain was committed in principle, by a treaty concluded in 1839, to guarantee Belgian independence and neutrality. In 1906 the Foreign Office had observed that this pledge did not oblige Britain to aid Belgium ‘in any circumstances and at whatever risk’ but, realistically, the huge threat posed by Germany to the balance of power and the Channel ports had to be resisted. Moreover, it proved much easier for Britain’s Liberal Cabinet to rally the nation behind a war for ‘gallant little Belgium’ than behind an abstract concept such as the preservation of the status quo or the balance of power. Britain’s own ultimatum expired without reply at 11pm (London time) on 4 August and she declared war on Germany.

Osprey has a wide range of books looking at the Great War. To see them all check out the World War I section of our store.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment