Cold War Delta Prototypes is the fascinating history of how the radical delta-wing became the design of choice for early British and American high-performance jets, and of the role legendary aircraft like the Fairey Delta series played in its development. On the blog today, author Tony Buttler gives a brief overview of his fantastic new release.

Readers who know the author’s work will be very familiar with his passion for researching and writing about the design and development of military aircraft. This interest covers in particular the period stretching from the mid-1930s until the 1970s, after which aircraft began to be created using computers. The result from then on was that new aircraft from different manufacturers, and indeed different nations, could look quite similar, or at least employ the same configuration. However, the days when slide rules and large mathematical calculations were used to produce new designs were also the days when Britain and America still had many different aircraft manufacturers. Consequently, proposals to any new Air Force or Navy requirements could produce a number of widely differing shapes and layouts with high or low wings, single or twin engine powerplants, etc., and all aimed at fulfilling the same role. And this was pretty well the case worldwide for all of the nations which possessed a substantial aircraft industry!

Nevertheless, during the 1940s and 1950s two manufacturers might sometimes produce very similar designs to the same requirement, in fact one might say almost by accident. What is even more fascinating was that on the odd occasion manufacturers on different sides of the world built and flew aircraft that were remarkably similar. For example, during the 1940s de Havilland in the UK produced the piston-powered Mosquito and followed it with the Hornet, whilst FMA in Argentina built the IAe 24 Calquin and then the IAe 30 Ñancú, which looked near identical and were intended to fulfil similar roles.

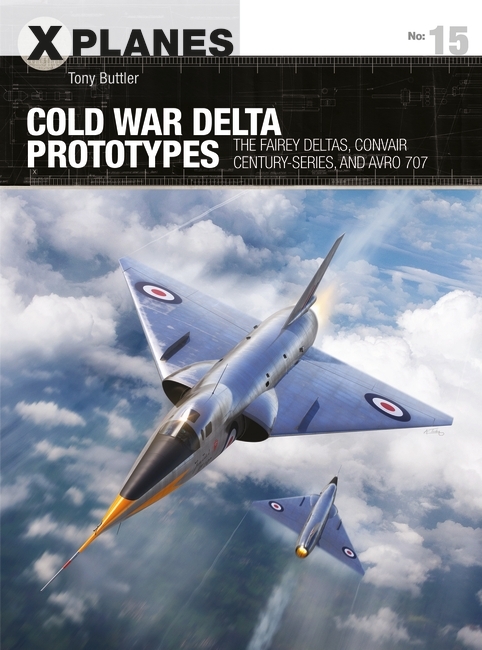

This book deals with an even more extraordinary comparison, the creation of two complete series of delta wing jet fighter designs during the 1940s/50s by aircraft companies based on each side of the Atlantic, Fairey Aviation in the UK and Convair in America. Never before have these programmes been brought together and compared side-by-side as it were within a single volume. The book shows how the two manufacturers both adopted the triangular delta wing shape for their new high performance fighters, each after having begun with essentially a delta wing research aeroplane. The big difference came when Convair went on to achieve considerable success with production runs for two of its machines (plus the B-58 Hustler delta-wing supersonic bomber), when Fairey failed to win any orders for its proposed fighter developments. The Delta II had shown extraordinary potential and had the British firm been successful in gaining production orders, then the history of the UK’s military aircraft since then could have been quite different.

Convair did have its failures too – the Sea Dart water-borne fighter prototype proved to be a dead end. And there was a third fighter manufacturer in the West who adopted the delta for a series of supersonic fighters (and a bomber) and which also sold in great numbers, Dassault of France. (During the 1950s the primary fighter Design Bureaus in the Soviet Union, Mikoyan and Sukhoi, also produced leading supersonic designs fitted with delta wings.)

Unfortunately, the X-Planes format does not have sufficient space to include the French family as well, but what has been added is a short study of the British Avro 707 prototypes. These were research aircraft designed to prove the delta wing for one of Britain’s new bombers, the famous Vulcan, and the object of this final chapter was to show how versatile the delta wing could be. Fairey and Convair had proved how suited it was for very high speed supersonic fighters, when Avro could confirm that it provided sufficient lift to enable a much larger subsonic aircraft to deliver a considerable load of bombs from high altitude.

With the arrival of the new jet engine, the 1940s and 1950s were perhaps unique in terms of the ground covered in raising the speed, performance and capability of new fighters and bombers. But for them to take full value of the ever increasing power output from these new engines, their designers had to adopt very advanced aerodynamic wing shapes, and in general the industry worldwide selected either the swept back wing or the delta. Today the swept wing is still employed on many new aircraft, but one might argue that it is, or was, the adoption of the delta which most represented the incredible progress made during this period.

To illustrate the point, in September 1946 a straight wing Gloster Meteor broke the world airspeed record when it recorded a figure of 616mph (991km/h). In March 1956, less than 10 years later, the Fairey Delta II featured in these pages took the record figure some 500mph (805km/h) higher when it recorded 1,132mph (1,821km/h).

This book brings together and compares three delta wing aircraft programmes that were ongoing all at the same time. This truly was a remarkable period in aviation history

Cold War Delta Prototypes publishes today! Order your copy from the website now.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment