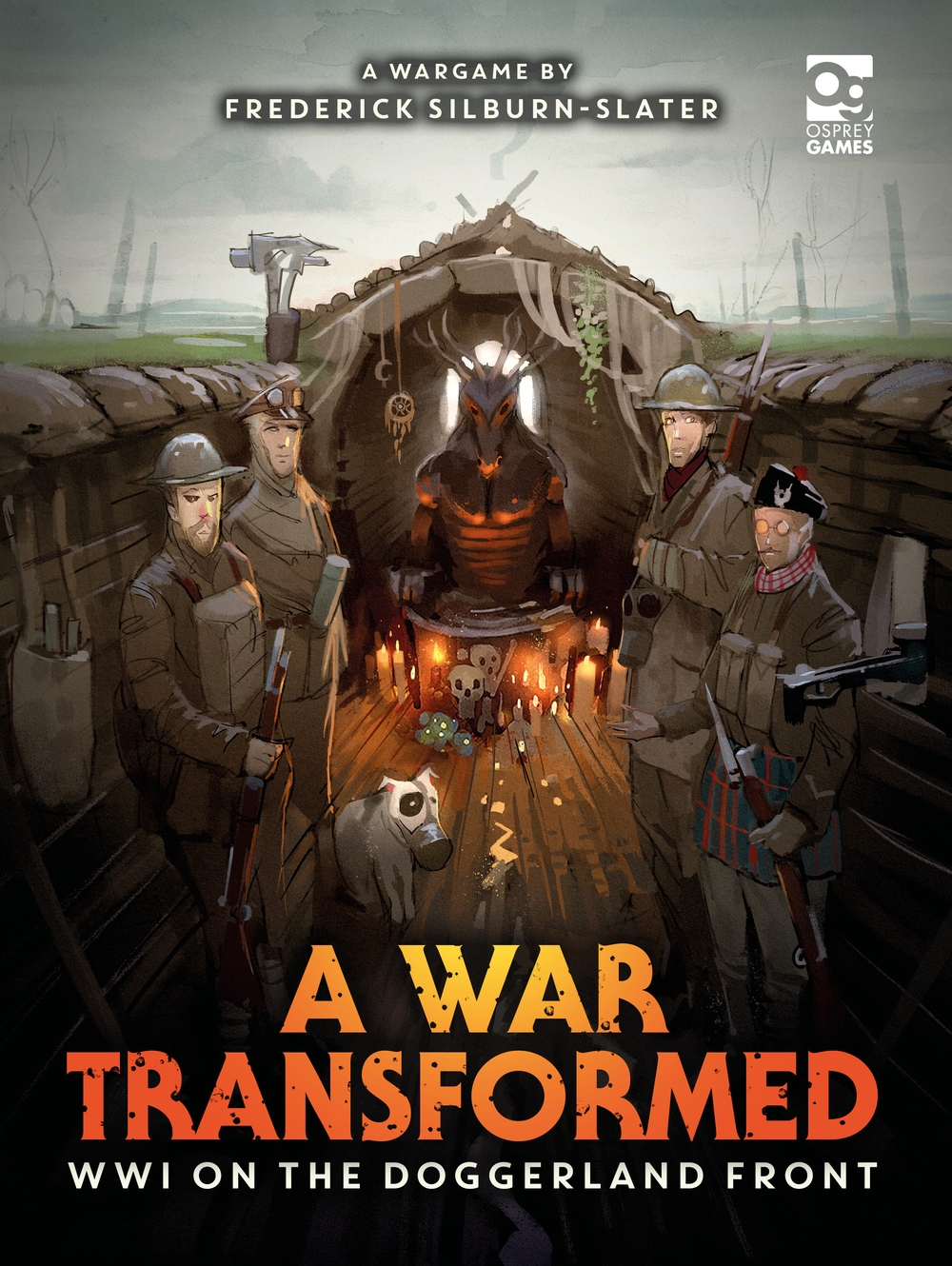

With one week to go until the release of A War Transformed, it's time for our last blog from author Frederick Silburn-Slater, all about the worldbuilding behind the game's folk-horror, Weird War One setting...

Putting the Somme in Midsommar: The Folk Horror Roots of A War Transformed

A War Transformed is a folk horror wargame set against the backdrop of an altered First World War. In its universe, the impact of an asteroid with the moon has set in motion a chain of events leading to huge changes to the geography of Earth and an environmental catastrophe the likes of which the world has never seen. Through mysterious means, the damage caused by the asteroid has reawakened the old gods of the earth, entities closely linked to nature, growth, and the seasons, who are sustained by human souls. Only the continuation of the conflict and the expenditure of so much blood maintains the fragile fertility of the earth which hangs on a knife’s edge.

At the heart of A War Transformed is quite a simple idea.

Many wargames today flirt with the idea of environmental collapse, of the earth simply giving up. Humans, left to fend for themselves in these scenarios, invariably turn savage. Some games take place in burning deserts, a diesel-scented fever dream of punk-garbed biker gangs, and roaring V8s. Others are found on planets totally overrun by industry in far flung galaxies removed from our own by both distance and millennia. Yet more take place in dreary, sludgy worlds of mire, muck, and root vegetables…

I don’t mean to disparage these universes. They are the kind of games I love: for me, a game hits that sweet spot when it gives its players the tools to tell stories, both on the table and with their miniature collections. However, though these disparate worlds are uniquely compelling, they nonetheless share a dull palette – dingy browns and sombre greys. I wanted to create a different kind of apocalypse for my game: not brown, but green.

But how can we reconcile that with the First World War? After all, for many people the conditions of 1914 to 1918 are best summed up by one word – mud! When I first started thinking about developing a weird First World War game, I read about the “Zone Rouge”. This protected area, which persists in some form to this day, prohibits certain activities around the battlefields of Verdun, for fear of setting off unexploded shells. When government inspectors first came to the area in the months after the war had finished, they were shocked at the speed with which nature had returned – despite months of continuous shelling and the (literally) millions of tonnes of munitions which had been detonated in this small area, grasses, brambles and even trees were reclaiming the region with almost preternatural speed.

In fact, the battlefields of the First World War, even as the conflict was being fought, were significantly greener than many people imagine, particularly in both the earlier and later phases of the war when the fighting was considerably more mobile. That’s to say nothing of the war’s other theatres and the countless battles and skirmishes which took place far away from the narrow band of the Western front. Over the four year course of the conflict and across the continents, men fought and died in environments that were wildly different from the popular image of mud, trenches, and barbed wire. The idea of nature creeping back, just as she did so triumphantly on the battlefield of Verdun, is one of the central themes of the game that I would go on to create.

This exploration of the power of nature to reclaim spaces that man once tamed is a core part of folk horror, a style of horror which deals with ancient ritual, the spirits of earth and the struggle between civilisation and magic. In films and literature associated with the folk horror movement, the natural world is represented as wresting control away from humans, often by forcing them to submit to worship of a nature deity. Folk horror’s recent vogue is thus timely – the genre addresses our anxieties about climate change, globalism and our modern way of life. In the face of environmental collapse, the natural world reasserts itself, often violently, and with horrifying implications.

At the core of folk horror narratives is an anxiety about the fragility of civilisation – the idea that, beneath a thin veneer of society, a wilder, more savage way of life is ready to bubble up to the surface and reassert itself. In many of the most famous works in the genre, the established social order collapses due to a lack of food, leaving the people of an isolated community faced with a stark choice: to upend their value system, or starve. There may be other causes of the disintegration of the social order – fears of illness, anxiety about fertility, or simple distaste for modernity – but whatever their reasons for retreating from broader society these communities, which are invariably rural, descend into a kind of savagery that is, at face value, underpinned by a rational impulse. Appease the gods to survive; destroy the outsiders to preserve a way of life; kill the interlopers to prevent the recurrence of a greater evil…

Folk horror will almost always feature characters who find themselves trapped among, or in opposition to, a community with a radically different moral code. This mirrors the othering of the enemy in the First World War that was a major component of propaganda. Among the allies, the Germans were thought to be almost genetically predisposed to evil; savage Huns who would roast babies on spits, crucify captives, and render down their own dead to make tallow. On the other side, the central powers configured the fight against Russia and Serbia as the culmination of a racial struggle that had been raging for millennia – bold Teutons locked in mortal combat against the sub-human Slavs.

The final piece of the War Transformed puzzle, fitting with the natural setting and societal collapse, are the myths, monsters, and magic of folklore. A War Transformed takes place in a world where nature is in revolt – the wilderness reclaiming fields and villages, towns and cities. The transformative cosmic event that caused this verdant uprising has awakened the old gods of earth and sea, forest and meadow from their slumber. Returning to the world from the spiritual realm into which they retreated as civilisation advanced, they demand again the sacrifices that were made to them long ago to ensure the fertility of the land. Mankind faces a difficult choice: submit or starve.

Lunar mythology plays a pivotal role in the universe of A War Transformed, as do the occult traditions of the early 20th century. In this period, mystics and thinkers attempted to reconstruct the beliefs of pagan peoples of the mythic past. In many of the resulting systems of belief a lunar goddess has a central role, one who changes in character with the progression of the lunar cycle, or one who has different avatars that control the different phases – waxing, full and waning. Often this lunar goddess or her avatars were conflated with known goddesses from the ancient world: Isis and Minerva gained new worshippers in the fashionable drawing rooms of Edwardian England, whilst secret societies in Germany revived the worship of the likes of Freya and Ostara. In A War Transformed, players can chose to devote their force to the Maiden, Mother, or Crone: avatars of the waxing, full and waning moons. Players can also choose to devote their forces to the Horned god, a masculine counterpart to the lunar goddesses and master of the hunt.

Often in folk horror there is a demagogue: a preacher or priest who rules on behalf of a god or goddess, interpreting their will and directing the community against the threats posed by outsiders. A War Transformed features witches, mortals and trusted servants of the old gods granted access to powerful ritual magics that give players new tactical options and ways to theme their armies.

Alongside the gods come creatures of myth; monsters from beyond the veil that separates the material world from the spiritual. Half-remembered in folklore and legend, they wreak havoc on the battlefields, summoned to the fighting by those of sufficiently strong will to dominate them. Creatures in A War Transformed are archetypes; blank canvases with traits common to monsters familiar from the legends of cultures from across the world. There are ethereal creatures of smoke and shadow, who stalk no-mans-land feeding on fear; pernicious beings who lure men to a watery demise through glamours, seduction or trickery; hideous monsters with an insatiable need for human flesh; and more besides! Players can interpret these categories as they wish, adopting existing creatures from folklore, or creating their own from scratch.

A War Transformed is, above all, a blank canvas for players to explore their own dark visions of war on the Doggerland front. Will you lead a fanatic cult, devoted to the worship of a savage god? Or lead a brave band of men fighting against the darkness? This and much more are available to you in the twisted world of A War Transformed.

A War Transformed is out a week today in the UK and 31st October in the US!

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment