Great Britain would not have been able to wage war as it did during the American Revolution without the assistance of a number of German states, most notably that of Hessen-Cassel. Despite pre-existing colonial discontent, the outbreak of armed hostilities in April 1775 caught both the British government and its military badly unprepared – the peace-time army was small, and augmentation and expansion to the size required to wage war first in North America and, after 1778, across the globe, would take considerable time.

Britain had a history of military alliances with various Protestant German states. Hessen-Cassel in particular had assisted Britain militarily during the Jacobite Risings of 1715 and 1745, the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years’ War. The need for a large number of professional soldiers who could be deployed at relatively short notice ensured that, as fighting escalated in the American colonies, Britain decided once more to turn to its dependable allies.

Of course, the use of emergency manpower led to what we might today term “bad optics.” It took little effort for American propagandists to decry the use of “foreign mercenaries” against a population that, in the early years of the Revolution, still overwhelmingly considered itself to be British. Such problems were considered secondary by British military planners who had decided that the best course in 1776 was a decisive show of force. For that the thousands of soldiers the Hessian landgrave was able to supply – in two separate expeditions departing from Hessen-Cassel in February and May respectively – were vital.

The Hessians corps certainly played its part. Arriving in time for much of the New York campaign of late 1776, the Hessian regiments were numerous enough to form two brigades, which the British commander-in-chief, Sir William Howe, soon started relying upon to spearhead assaults. The Hessians met with near-uninterrupted success, especially at the battle of White Plains and the storming of Fort Washington.

That all changed after the close of the campaigning season. The Continental Army, founded just the year before, had endured against the odds under George Washington, surviving the defeats around New York and the hard retreat through New Jersey. Despite the losses inflicted, valuable lessons had been learned, and certain units and commanders had acquitted themselves well. Desperate for a victory that might show both the British, and Congress, that the revolution was still far from defeated, Washington and his subordinates conceived of their most daring operation yet.

In keeping with the fact that they were considered reliable troops, Hessian detachments were stationed in two of the New Jersey outposts closest to the Continental Army across the Hudson River in Pennsylvania, at Trenton and Bordentown. It was against the former that Washington launched a surprise attack on December 26, 1776.

If the preceding months had convinced many that the colonials were no match for their enemies, Trenton changed that. Continental forces conducted a complex offensive operation that caught the Hessians heavily underprepared. Assaulting from multiple directions and making excellent use of combined arms, with artillery in close support of their infantry, Washington’s forces overwhelmed and compelled the surrender of the Trenton garrison after barely half an hour of fighting. The leader of the Hessian contingent, Johann Rall, a veteran officer who had distinguished himself during the recent New York campaign, was mortally wounded leading the defense. Less than a week later, the Continentals again launched a daring offensive strike that culminated in another victory at the battle of Princeton, this time over British regulars. While these engagements were not large-scale, they proved that not only were the Continentals far from beaten but, under the right circumstances, they were the equal of their enemies, whether British or Hessian.

It can be argued that the Hessen-Cassel corps never truly recovered from the shock of Trenton. The senior Hessian commander, Leopold Philip von Heister, was pressured into relieving command, and it seems as though the British view of their allies suffered. Hessian forces still served Howe well – at the battle of Brandywine, for example, they pinned George Washington’s attention before storming his defences at Chadds Ford. Heavy losses were again suffered in 1778, however, during a botched attack against Fort Mercer, outside Philadelphia. The elite of the Hessian forces, the composite grenadier battalions, were decimated by the massed firepower of dug-in Continental infantry, and another senior officer, Carl von Donop, was killed.

Following the British withdrawal from Philadelphia in 1778, there were no more large-scale engagements between Hessen-Cassel and Continental brigades. Small numbers of Hessians, such as the Regiment von Bose or elements of the jäger corps, served with distinction during the Southern campaigns of 1780 and 1781, but must of the Hessian corps remained with the main British field army in and around New York during the later years of the war, which in turn meant they were removed from sustained campaigning. While the overall Hessian combat record in North America remained a good one, by the war’s end there was no doubt that the Continental Army had learned how to face these infamous German troops on equal terms.

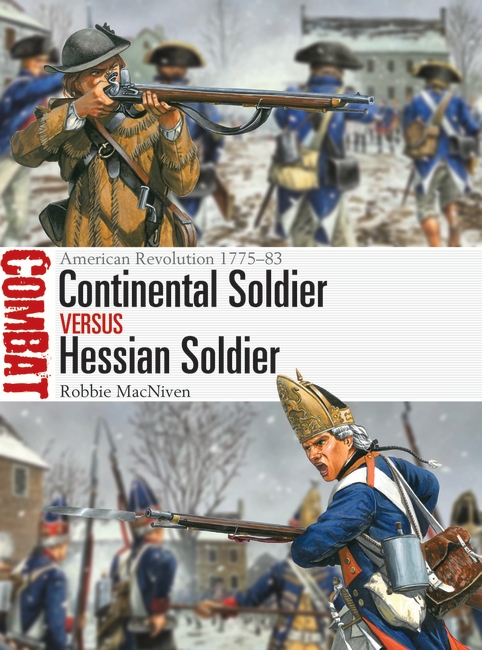

You can red more in Continental Soldier vs Hessian Soldier: American Revolution 1775–83

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment