When Tom Milner asked me if I would be interested in taking over the production of a book on the last major German bombing campaign of the Second World War, I willingly accepted. Being an aviation historian who majors on German air operations over north-west Europe and having written a number of books on the Luftwaffe, including the Battle of Britain (1940), Blitz (1940–41) and Baedeker Blitz (1943), this was to me a logical next step.

By the second half of 1943, the skies over Britain were a dangerous place for the Luftwaffe. Attacks by daylight were rare due to the potency of the RAF while in attacks by night – even if the German crews were afforded darkness as protection – superior RAF nightfighters, much-improved radar and anti-aircraft guns wreaked a heavy price on the Luftwaffe.

Meanwhile over Germany, the USAAF was bombing German targets by day and the RAF by night. Such punishment against the Germans warranted some kind of response but the problem was how. The daylight 'tip and run' attacks by German fighter-bombers had ended on 6 June 1943 and using Focke-Wulf 190 fighter-bombers at night was now not having the desired effect. New aircraft such as the Ju 188, Ju 88S, Me 410 and Do 217 K and M were starting to appear in German units, although slowly thanks to the bombing of German factories, and their numbers were insufficient. Furthermore, the long-awaiting four-engined He 177 only went operational in the maritime attack role in November 1943 and so far had not been tried as a conventional bomber; that testing would come in January 1944.

German leaders wanted to do something, or to be seen to be doing something. That something became Operation Steinbock, which would throw German bombers, sometimes in two waves in one night, against London. The idea was rushed through. It was first suggested in earnest in early December 1943 with an aim to start before the end of the year. That did not happen, as it was not until the night of 21 January 1944 that Steinbock started.

The first night was not as roaring a success as was hoped. Of the 227 aircraft said to have taken part, few made it to London and a number were shot down. An incredible 16 Ju 88s, two Ju 188s, eight He 177s, one Fw 190, one Me 410 and four Do 217s were either lost to British defences or crashed on the way to or from the target, due to technical problems or combat. In terms of the human cost, 74 aircrew were killed or missing, 15 captured and eight wounded or injured on the two raids this night. As the British said afterwards:

“The attack was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, only 14 aircraft succeeded in reaching London and in the second 13. As a result there was considerable spill, mainly in south-eastern England; in Kent alone over 100 minor incidents occurred. In London, the bulk of the incidents were south of the River. A considerable number of unexploded bombs and incendiary bombs were dropped and considering the scale of effort, the results were very poor and compared unfavourably with those of the attack on Birmingham on 29–30 July 1942.”

Furthermore, given the limited numbers of He 177s, to lose eight to various causes on the first night of the type being used for conventional bombing was nothing short of a failure. As a German general said to Hitler at the end of January 1944:

“One gets the impression that once again the He 177 has suffered 50% breakdowns. They cannot even get as far as London. This heap of c**p is obviously the biggest load of rubbish that was ever manufactured. It is the flying Panther [the Panther tank suffering from poor reliability] and the Panther is the crawling Heinkel!”

Despite an inauspicious start, the campaign stuttered on until all eyes and effort turned to Normandy from 6 June 1944. The losses suffered bled the German bomber arm almost dry, and as to the campaign as a whole, it is best summed up by General Dietrich Peltz, who was in operational command of Steinbock. After the war, he was quoted as saying:

“The attacks on London and other British cities were, in my opinion, like a few drops of water on a hot stone – a bit of commotion but after a very short time the whole thing was forgotten.”

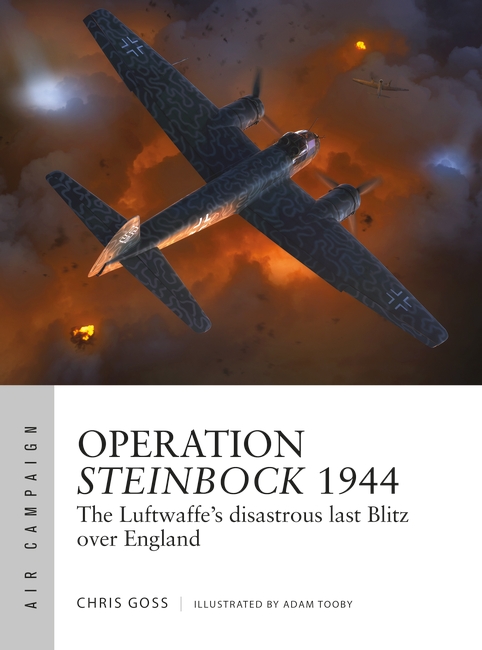

You can read more in ACM 52 Operation Steinbock 1944: The Luftwaffe's disastrous last Blitz over England by Chris Goss.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment