The war fought in Yugoslavia following the occupation and dismemberment of the country in April 1941 is, without a doubt, the best-known case of a successful campaign fought by a partisan movement during World War II. The Yugoslav Partisan Army, led by Tito (pseudonym of Josip Brôz), managed to survive the various offensives conducted by the occupying forces for three and half years, eventually succeeding in liberating the country with the help of the advancing Red Army. This image dominated the post-war historiography and public image until Tito’s death, the role and importance of the leader and his partisan army being celebrated by books and movies. The reality, revealed shortly after his death, was much more complicated. Yugoslavia proved to be a country deeply divided, just as it was in 1941 when it was first occupied by the Axis forces.

The first step in understanding the 1941–44 war fought in Yugoslavia is to examine the initial partition of the country following defeat. Germany only annexed a limited portion of the country, part of Slovenia, as did Hungary, which annexed areas along the Drava River. Bulgaria annexed part of southern Yugoslavia along the border with the region of Kosovo, which was split with the Italians. The latter took the lion’s share, annexing part of Slovenia, the entire coastal area of Dalmatia and, in a non-official capacity, Montenegro, which was created as an independent area under Italian control. The two states emerging from the dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Croatia and Serbia, were respectively under Italian and German control, the latter being militarily occupied and run by a puppet regime. Croatia, led by Ante Pavelić and his Fascist Ustasha party, soon saw ethnic cleansing where Croats moved against Serbs and other minorities.

Italian soldiers in Yugoslavia in the summer of 1941. In spite of its actual strength, the Italian Army failed to fight effectively the insurgency almost everywhere, except Montenegro. (Muzej revolucije naroda Jugoslavije via ZNACI)

Italian soldiers in Yugoslavia in the summer of 1941. In spite of its actual strength, the Italian Army failed to fight effectively the insurgency almost everywhere, except Montenegro. (Muzej revolucije naroda Jugoslavije via ZNACI)

The birth of the anti-Axis movement in Yugoslavia was also confused. Two parties emerged, each with its own agenda and conflicting aims. Tito’s Partisan movement, originating mainly from Serbia, was mostly politically motivated and had strong ties with the Soviet Union. The Chetnik movement, led by Dragoljub ‘Draža’ Mihailović, was created to defend the ethnic Serbian minorities. Its aim was the creation of a ‘Great Serbia’, as opposed to the idea of the restoration of Yugoslavia as pursued by Tito, and as such intended to fight every enemy of the nation, including the Communists. The birth and subsequent spread of the insurgency in the summer of 1941, mostly in Serbia and Montenegro, led to contrasts between the two movements, which soon started fighting one another. In the meantime, the Italians and the Germans delivered a series of counter-offensives which pushed away the partisan groups, mostly to Bosnia.

The subsequent evolution of Tito’s Partisan Army and of Mihailović’s Chetnik movement is revealing of the deep fractures within the anti-Axis resistance movements. The first attempted to create some ‘free-zones’ where it could grow, organise and live off the land. The second developed mostly as a local fighting force, and soon made deals with the Italian and German forces to secure survival and its own aims, fighting both Tito’s Partisans and the Croats alike. The sorry conditions of Pavelić’s Croatia, its armed forces being slow in its organisation and development, practically merged the resistance movements, the Chetniks in particular, with their ethnic component. From 1942, the war fought in Yugoslavia was not just a partisan war but also an ethnic one. It saw the Chetniks fight the Croats (the political Ustasha and the army, the Domombran). In contrast, Tito’s skill saw the creation of an actual Yugoslav Partisan Army encompassing all the ethnic minorities in the country.

Partisans manning an Italian 75mm gun deployed on a mountain top. (NARA)

Considering that neither Tito nor Mihailović could rely on any kind of external help, at least until late 1943, it is quite surprising that both the Partisans and the Chetniks managed to survive, isolated and constantly hammered by the anti-partisan actions conducted by the occupying armies. In the case of the Chetniks, their survival mostly depended on the deals made with the Italians, and partly with the Germans, thanks to their opposition to Tito’s Partisans. Tito’s Partisans were able to survive thanks to the weaknesses of the Axis forces in Yugoslavia.

Part of the ‘Partisans’ Myth’, created after the war, is related to the persisting image of the strength of the German forces. Until 1943, the Germans only engaged a limited number of units in both Serbia and in Croatia; two divisions were only temporarily deployed to fight the partisans before being transferred to the Eastern Front. Until the end of 1942, the German forces in Yugoslavia consisted mainly of four garrison divisions. They were eventually reinforced by the Waffen-SS ‘Prinz Eugen’ Division, which was raised locally from German ethnic minority populations. There was also a shortage of commands. The Germans created an operational command for Croatia only in 1942, even though their forces had been fighting in the area for the previous year already. This consistent shortage – which was partly made good in early 1943 thanks to the creation of the first Croatian ‘legionnaires’ divisions – clearly reflected the German attitude towards the country. Germany’s main goal in Yugoslavia was to secure the supply of raw materials, which did not necessarily require the presence of German troops. In December 1941, Hitler, facing the crisis on the Eastern Front, even considered handing over control of areas of German occupation to the Italians to spare forces to use against the Red Army. The idea eventually fell through, mostly because of the unreliability of the Italians and their persistent inability to deal with the partisan insurgency.

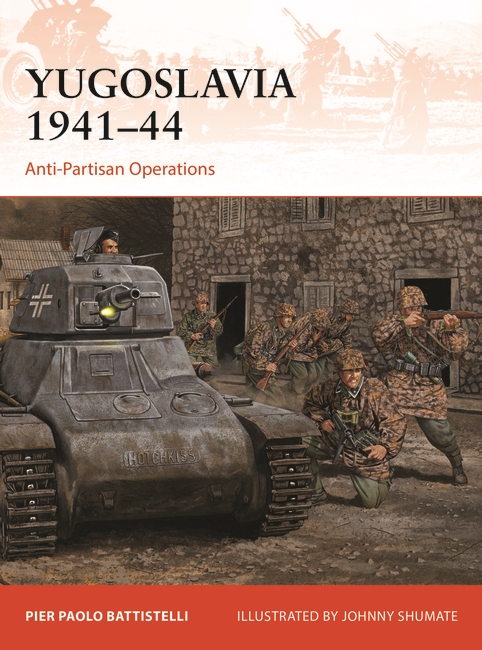

Men of the Waffen-SS ‘Prinz Eugen’ Division mopping up a village with the support of French Hotchkiss tanks. (NARA)

Men of the Waffen-SS ‘Prinz Eugen’ Division mopping up a village with the support of French Hotchkiss tanks. (NARA)

Only in late 1943, following the Allied invasion of southern Italy, did Yugoslavia acquire importance in German strategy. In Hitler’s view, the Allies would realise the insignificance of Italy and turn towards the Balkans, where a landing could be helped by the strong presence of the anti-Axis resistance movements. From there, the Allied armies might drive towards southern Russia, linking up with the Red Army in a strategically vital area. This strategic thinking led to Operations Weiss and Schwarz in 1943, large-scale operations to remove the Partisan presence from key areas of the country. From the end of 1943, after the Allied strategy to fight along the Italian peninsula became clear, the role of the German forces in Yugoslavia greatly diminished, even though, following the Italian defeat, they were occupying most of the country.

It is clear that, from 1941 to early 1943, the Italians did have a key role in the anti-partisan war in Yugoslavia, which may also explain how Tito, and to some extent also Mihailović’s Chetniks, managed not only to survive but also grow in size and importance. The Italian forces, approximately about a quarter of the strength of the entire Italian Army, garrisoned the annexed area of Slovenia, the coastal area of Dalmatia (annexed, also known as ‘Zone 1’) and Montenegro. The agreements with the Croats had created a buffet zone (known as ‘Zone 2’), a demilitarised zone between the annexed area and the demarcation line between the German and the Italian forces in Croatia, in which Croatian troops were supposed to operate only with Italian consent. After a temporary withdrawal in the summer of 1941, the Italians moved back into ‘Zone 2’ following unrest due to Ustasha violence. This was followed by the advance into the ‘Zone 3’, reaching the demarcation line between the German and the Italian forces. Given their strength, and the actual occupation of about one third of Croatia, the Italians should have been able to crush Tito’s Partisans without issue. They did not, for a wide variety of reasons.

The story of the Partisan war fought in Yugoslavia in 1941–44 is much more complex than usually imagined. It involved several parties and was broken into a series of struggles from which only Tito managed to emerge victorious. This book provides insight into this historical maze of long-lasting consequences.

You can read more in Yugoslavia 1941–44: Anti-Partisan Operations.

Comments

You must be logged in to comment on this post. Click here to log in.

Submit your comment